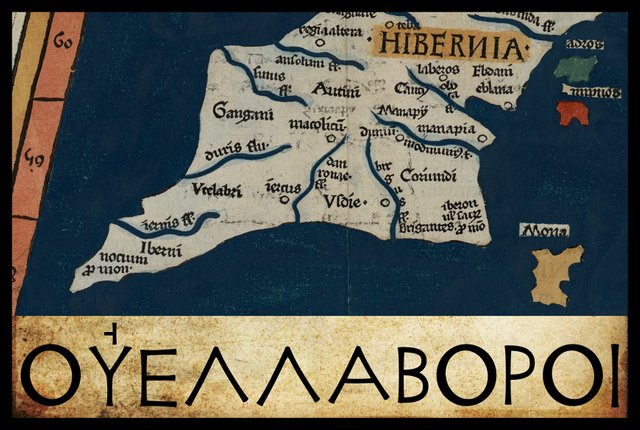

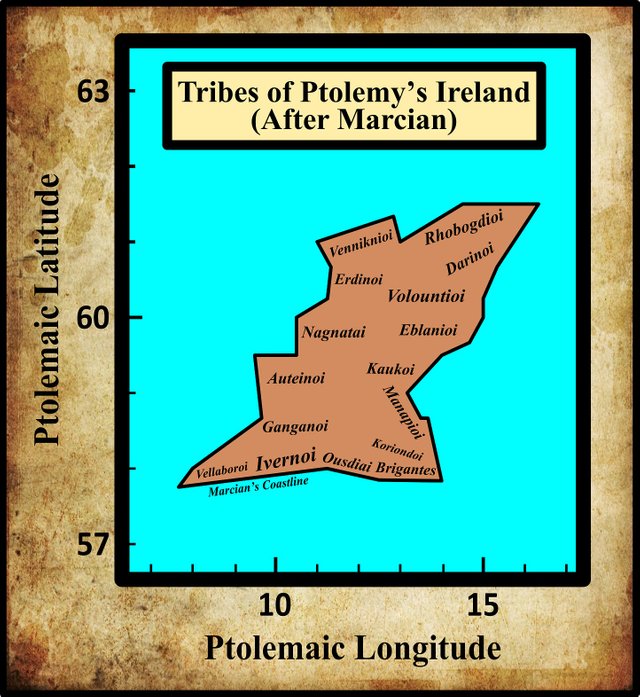

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the disposition of sixteen Irish tribes. Resuming our voyage around the island, the fourteenth tribe we encounter are the Vellaboroi (Latin: Vellabori). Ptolemy places these people immediately south of the Ganganoi. They are the last tribe enumerated on the west coast.

In his 1883 edition of the Geography, Karl Müller notes no less than seven variant readings of this ethnonym in § 4. One of these differs from the critical form only in its application of the Greek accents. As the use of these accents was not regularized until the Byzantine era, they are generally considered to be “without authority” (O’Rahilly 1 fn 2, Gnanadesikan 220-221). In his 1838 edition of the Geography, Friedrich Wilberg notes five of Müller’s variants, though his critical choice differs from Müller’s. Wilberg also records a few variants that differ from one another only in their use of accents. In his edition of 1845, Karl Nobbe agrees with Wilberg’s choice of the critical form.

The alternative reading that has been added to three of the manuscripts (B, E and Z) is recorded by both Müller and Wilberg as Ἐλλεβροι [Ellebroi], but the correct reading is clearly Ἐλλαβροι [Ellabroi] in B and E, which are now available for online viewing:

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| A | Οὐελλαβοροι | Vellaboroi |

| B, E, Z | Οὐελλεβοροι | Velleboroi |

| F | Οὐλλαβοροι | Oullaboroi |

| D, M, P, W, Δ, Ξ, Π, ב | Οὐελεβοροι | Veleboroi |

| C, V, R, α | Οὐελιβοροι | Veliboroi |

| X, Σ, Φ, Ψ | Οὐτελλαβροι | Outellabroi |

| B, E, Z | Ἐλλαβροι | Ellabroi |

| Source | Latin | English |

|---|---|---|

| 4803 | Vtelabri | Utelabri |

A is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1401.

B is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1404. Like E and Z, this manuscript has the reading Οὐελλεβοροι [Velleboroi], but someone has added the variant Ἐλλαβροι [Ellabroi]: “οἱ καὶ ἐλλαϐροί” [hoi kai ellabroi = and the Ellabroi]

C is Parisiensis Supplem 119. Presumably this is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, though I have not been able to confirm this.

D is another of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1402.

E is another of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1403. Like B and Z, this manuscript has the reading Οὐελλεβοροι [Velleboroi], but someone has added the variant Ἐλλαβροι [Ellabroi]: “οἱ καὶ ἐλλαϐροί” [hoi kai ellabroi = and the Ellabroi]

F is Coislin 337, one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. It is believed to date to the 14th or 15th century.

M is Vindobonensis 1, a codex in the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

P and R are Venetian manuscripts identified by Müller as Venetus 383 and Venetus 516. They are possibly kept in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, though I have not been able to confirm this.

V and W are two manuscripts in the Vatican Library, Vaticanus Graecus 177 and Vaticanus Graecus 178.

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is believed that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v–139r.

Z is Vaticanus Palatinus Graecus 314, a Greek manuscript from the old Palatinate Library of Heidelberg, which is now part of the Vatican Library in Rome. Like B and E, this manuscript has the reading Οὐελλεβοροι [Velleboroi], but someone has added the variant Ἐλλαβροι [Ellabroi]: “οἱ καὶ ἐλλαϐροί” [hoi kai ellabroi = and the Ellabroi]

Δ is Florentinus Abbatiae 2380, a codex from the Abbey of St Lawrence in Florence.

Ξ is Barberinus, a codex from the library of Cardinal Francesco Barberini. It is now housed in the Vatican Library

Π This manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography was formerly in the Library of St Gregory on the Caelian Hill in Rome. In 1872 the government of the recently established Kingdom of Italy confiscated the contents of the library, which were subsequently dispersed. Many of the volumes were expropriated by the Vittorio Emanuele II National Library of Rome.

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

α is identified by Müller as the Codex Ingolstadiensis. He refers to it as the Editio princeps, a term generally reserved for the first printed edition of a work. Today, the editio princeps is usually credited to Erasmus, whose complete Greek edition—based on a manuscript provided by Theobald Fettich of Kaiserslautern—was published by Hieronymus Froben in Basel in 1533. Earlier in the same year, however, Peter Apian of Ingolstadt published an incomplete version of the Geography in Greek and Latin. I can only assume that Müller’s Cod α is a copy of this work.

ב is identified by Müller as Scorialensis Ω, I, 1. This is a manuscript in one of the libraries in the royal seat of El Escorial in Spain.

4803 is one of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. It is a Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803.

To confuse the issue, Ptolemy refers to the Vellaboroi again in § 6. In this instance, the ethnonym occurs in the accusative plural rather than the nominative plural. Once again, however, there are a plethora of variant readings in the manuscripts. Not only do the manuscripts contradict one another, but in many cases they contradict themselves, having different readings for the same ethnonym in § 4 and § 6. In the following table, the tribal name has been transcribed as the implied nominative plural:

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| A, D, L, M, N1, O, P, R, V, W, Ξ, Π, α | Οὐελλαβοροι | Vellaboroi |

| D, N2 | Οὐελλεβοροι | Velleboroi |

| Σ, Φ, Ψ | Οὐενλαβοροι | Venlaboroi |

| B, L2 | Οὐελλαβροσοιι | Vellabrosioi |

| X, Arg | Οὐτενλαβροι | Outenlabroi |

| X, Arg | Οὐτελλαβροι | Outellabroi |

| Source | Latin | English |

|---|---|---|

| 4803 | Vtelabri | Utelabri |

L is a manuscript from the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.

N and O are Oxoniensis Seldanus 2, 46 and Oxoniensis Seldanus 2, 45, two of the Selden Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

Arg is the Editio Argentinensis, which was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

Müller makes a distinction between N1 and N2 and between L and L2, but he never clarifies what these distinctions entail.

One can see why Müller adopted the reading Οὐελλαβοροι [Vellaboroi] as the critical form. It is the commonest reading in § 6, even though it is attested by only a single manuscript in § 4. Wilberg and Nobbe’s choice, Οὐελλεβοροι [Velleboroi], is the commonest reading in § 4, but is found in only two manuscripts in § 6.

So which of the many variant readings is the correct form? The choice, it seems, is between Müller’s Οὐελλαβοροι [Vellaboroi] and Wilberg & Nobbe’s Οὐελλεβοροι [Velleboroi]. The other variants can all be dismissed as transmissional errors that are only found in one or two sources. As it happens, the 5th-century historian Paulus Orosius refers to a particular Irish tribe as the Velabri. Added to the linguistic evidence (see below), this suggests that Müller’s critical form is superior to Wilberg and Nobbe’s.

A Note on Ptolemy’s Use of Breathings

In Celtic, v was pronounced like our modern semivowel [w], as it was in Classical Latin. In later forms of Irish, [v] and [w] are found, depending on the context and the dialect. As we have seen several times before in this series, Ptolemy used the Greek digraph ου [ou] to represent the Celtic letter v because the Greek letter digamma, which had formerly represented this sound, had fallen out of use (except as the numeral 6). T F O’Rahilly explained this practice in his Early Irish History and Mythology in connection with the Greek names for Ireland:

The name ’Ιέρνη, “Ireland”, had probably been picked up by the Massaliot Greeks, from merchants and from their Celtic neighbours, as early as the fifth century B.C. ... The digamma had disappeared from Ionic as early as the seventh century B.C.; and when Massaliot Greeks first heard the name Īvernā [Ireland], they presumably had no means of indicating the -v- and simply dropped it. Later the Greeks adopted the expedient of representing v in foreign names by ου ... We may take it that Pytheas [believed by O’Rahilly to be Ptolemy’s principal source for information about Ireland] retained the traditional name ’Ιέρνη ... whereas in dealing with other names previously unrecorded, we find him representing Celtic v by Greek ου, as for instance in ... Bouvinda [Βουουινδα] ... Ptolemy, or some near predecessor of his, modernized ’Ιέρνη into ’Ιουερνία [Ivernia] ... (O’Rahilly 41-42)

Once again I quote Amalia Gnanadesikan, the Technical Director for Language Analysis at the University of Maryland’s Center for Advanced Study of Language, on the use of diacritics in ancient Greek. In her book The Writing Revolution, she makes the following pertinent comment on the question of smooth and rough breathing in Ptolemy’s Alexandria:

In the process of accumulating and copying texts, the Alexandrian scholars began to show concern for matters of orthography. They found that at certain points the lack of a written form of [h] made for ambiguity. They noted that the Greeks living in Italy had been more free-thinking than the Athenians. While they had gone along with the adoption of the Ionic alphabet, they continued to write [h] by cutting the hēta in half and using ├. The Alexandrians adopted the Italian Greeks’ half H, but wrote it as a superscript on the following vowel, so that, for example,

was ho. Loving symmetry, they made the other half of H stand for the lack of an [h] sound before a vowel:

These diacritics came to be termed “rough breathing” (for [h]) and “smooth breathing” (for lack of [h]). Their use was for many centuries largely reserved for cases where ambiguity could arise without them. These marks later became ‘ and ’, so that ὁ was ho and ὀ plain o ... Only by the ninth century AD (well into the Byzantine period, AD 330–1453) did the use of breathing and accent diacritics become fully regular, with all vowel-initial words marked for “rough” or “smooth” breathing and all words marked for accent. (Gnanadesikan 220 ... 221)

I take these remarks to imply that Ptolemy probably only employed the diacritics for smooth and rough breathings in cases where the correct reading was not already obvious to the reader. In other words, he probably did not include the breathing in common Greek words, as its presence in such words was too well known to require inclusion. In the case of foreign toponyms and ethnonyms, however, he probably did include it. Hence we have Ἰουερνις rather than Ιουερνις.

Unfortunately, Gnanadesikan does not consider the exceptional case where an initial ου- [ou-] represents the Celtic semivowel spelt V and pronounced [w]. Did Ptolemy include the smooth breathing in this case? I have decided to include the smooth breathing, since it is included in the surviving Byzantine manuscripts. Hence, I have Οὐελλαβοροι rather than Ουελλαβοροι.

O’Rahilly and Mac Neill

In his Early Irish History and Mythology, T F O’Rahilly had much to say about this ethnonym:

Vellabori. This tribe, dwelling in the south-west of Ireland, is also mentioned by Orosius, who calls them Velabri. The River Roughty was formerly known as Labrann, which may come from *Labaronā (p. 4), with which compare Labarā, the Celtic name of several Continental rivers, Ir. labar, ‘talking boastfully, chattering, talkative’, W. llafar, ‘loud, vocal’. This suggests that Vellabori is perhaps to be emended to *Vellabari, which may be analyzed as = ver- + labarī, for the change of rl to ll appears to have occurred in Celtic as in Latin. (O’Rahilly 9)

Another Irish historian, Eoin [John] MacNeill, had previously suggested a different emendation of Ptolemy’s text:

Vellabori (Ptolemy), Velabri (Orosius) seems to have left a trace in the place-name Luachair Fellubair (LL 23 a 17). This name occurs in a poem which aims at accounting for the distribution of the peoples said to be descendants of Fergus Mac Roig. Wherever Rudraige, the Ulidian king of Ireland, won a battle, his grandson Fergus planted a colony of his own race ... Of these colonies were Ciarraige Luachra (in North Kerry) and Ciarraige Cuirche (Kerrycurrihy barony, co. Cork) ... Ptolemy clearly indicates the Vellabori as inhabiting the south-western corner of Ireland, and Orosius speaks of the Velabri as looking towards Spain. In the verse cited, we should expect gp. Fellabor = *Vellabron, but the word may be used eponymically in gs. (MacNeill 1911:62)

Some decades later, MacNeill returned to this hypothesis:

In a paper on ‘Early Irish Population Groups’ (Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, xii, C 4, p. 62) I have shown that a reminiscence, and no more, of the Vellabori of Ptolemy, the Velabri of Orosius, is preserved in the single mention of the name Fellubair, found in a poem in the book of Leinster (23_a_ 17) ... so, in the poem, Fīch cath Curchu, cath Luachra, laechdu Fellubair, ‘He fought the battle of Curchu, the battle of Luachair, hero-home of Fellubar.’ Fellubair rhymes with Glendamain of the same strophe. The phrase laechdu Fellubair means the native place of the hero Fellubar (-bur). I have not found the name elsewhere, and particularly not in the ample genealogical account of the Ciarraige kindred, but the verse implies a known story of the hero, and the name must be a traditional reminiscence of the Vellabri, enabling us to correct to this form the names given from Ptolemy and Orosius. (MacNeill 1932:132-133)

O’Rahilly’s comment on this analysis:

On the other hand, Mac Neill has called attention to some words in a poem in the Book of Leinster L. G. [Book of Invasions] (23 a 17), viz. cath Luachra laechdu Fellubair (: Glendamain), which he translates ‘the battle of Luachair, hero-home of Fellubar’, taking Fellubar to be the name of some traditional ‘hero’ of whom nothing else is known; and as Fellubar would go back to *Vellabros, he suggests that the tribal name was (not Vellabori or Velabri but) *Vellabri. This may well be correct, at any rate for Goidelic; for whereas W. llafar can go back only to *labaro-, Ir. labar, Labrann, may equally well go back to *labro-, *Labronā. In favour of -br- in Irish we have the Ogam gen. LABRIATT[OS], = Mid. Ir. Labrada; and we may further compare Gk. λάβρος, ‘boisterous, impetuous’, λαβρεύομαι, ‘I talk boldly, brag’, which can hardly be disassociated from the Celtic words. (O’Rahilly 9-10)

In a footnote, however, O’Rahilly suggests that Fellubar may be a place-name rather than a personal name:

Or should we for laechdu read laeccath, ‘warrior battle’ (which would suit the context better), so that Fellubar, like Luachair, would be a place or district name? Mac Neill’s interpretation would require laechdu to be emended to laechdon (gen.) (O’Rahilly 9)

For reference, here is the relevant passage in Orosius:

Ireland, an island situated between Britain and Spain, is of greater length from south to north. Its nearer coasts, which border on the Cantabrian Ocean, look out over the broad expanse in a southwesterly direction toward far-off Brigantia, a city of Gallaecia, which lies opposite to it and which faces to the northwest. This city is most clearly visible from that promontory where the mouth of the Scena River is found and where the Velabri and the Luceni are settled. Ireland is quite close to Britain and is smaller in area. It is, however, richer on account of the favorable character of its climate and soil. It is inhabited by tribes of the Scotti. (Orosius 2:2)

As to the precise location of Ptolemy’s Vellaboroi, MacNeill notes:

In Ptolemy’s description, the Vellabri are the most southward people on the west coast of Ireland, the Iverni the most westward people on the south coast, but this does not show which people is held to occupy the extreme south-western region. His prepositions seem to indicate that the Iverni were to the east of the Vellabri. The Vellabri were ‘under’ (ὑπό), that is, south of the Gangani, but the Iverni were ‘after’ (μετά) the Vellabri. The ostium Scenae of Orosius gives no certain light. It becomes Inber Scene of the Irish migration-legend, having an undefined location in south-western Ireland, and is perhaps no more than an echo of Ptolemy’s Σήνου ποταμοῦ ἐκβολαί [Mouth of the River Sēnos]. If this last, as is likely, means the Shannon ... [the] district of ‘Luachair, laechdu Fellubair’ adjoins the mouth of the Shannon. (Mac Neill 1932:133)

Before leaving MacNeill’s and O’Rahilly’s analyses, I might point out that among the numerous variant readings of this ethnonym, there is no Οὐελλαβροι [Latin: Vellabri]. Ἐλλαβροι [Latin: Ellabri] is perhaps the closest.

Roman Era Names

The contributors to the website Roman Era Names also suggest that Ptolemy’s text is corrupt and should be emended, though they are unsure which emendation to prefer:

Ουελλαβοροι (or Ουτελαβροι) (Wellaboroi 2,2,5) in the very south of Ireland had a name that looks rather like the plant name ἑλλεβορος ‘hellebore’, which raises a suspicion that Ptolemy’s text has been corrupted, perhaps from something closer to the spelling Velabri of Orosius 300 years later. Presumably it was lack of any viable Celtic etymology that prompted De Bernardo Stempel (2000) to suggest that these people were ‘wallflower eaters’, from the roots of Latin/Gaulish vela ‘erysimum’ plus Greek βορα [bora] ‘food’. Better parallels may be Latin velum ‘sail’ plus boreas ‘north wind, northern’, meaning that these people were known for sailing to Iberia, a long voyage but easy to navigate since it was due north-south. (Roman Era Names)

It is curious that they do not even consider O’Rahilly’s “talkative” etymology. The less said about Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel’s wallflower eaters the better.

Martin Counihan

The independent researcher Martin Counihan follows both MacNeill (unacknowledged) and O’Rahilly:

About AD 416, Paulus Orosius wrote that the Irish coast looks out to the south-west towards the tower of Brigantia in Spain which is visible, he claimed, from the promontory where the mouth of the Shannon is found and where the Velabri and the Luceni are settled. Brigantia is now A Coruña, and the Irish promontory is presumably Loop Head.

The name of the Velabri, or Vellabori as it was written by Ptolemy of Alexandria, crops up in Irish tradition in connection with the Battle of Luachra, a prehistoric conflict recorded as having taken place within a district called Fellubar. Almost certainly, the Old Irish Fellubar and the Latin Vellabori are versions of the same name. Luachra is the name of a mountain near the border of Kerry with Cork and Limerick, an area centred some 30 km east of Tralee. This is consistent with the ancient Vellabori having been present in north Kerry.

Velabri may be analysed as ve-labri, from an earlier ver-labri, with ver = “more”, “above”, or “very”. Labri is from the Old Irish adjective labar, meaning “talkative”, “boastful”, or “arrogant”. So, Velabri meant something like “the very boastful people” in a culture where boastfulness and arrogance were regarded as noble virtues. (Counihan 10)

Earlier Scholarship

In the 16th century, the English antiquarian William Camden mentioned the Velabri as one of the native tribes of Munster. In his description of Desmonia or Desmond he wrote:

The Velabri seem to derive their name from Aber, i. e. Æstuaries; for they dwelt among Friths, on parcels of Land divided from one another by great incursions of the Sea; from which the Artabri and Cantabri in Spain did also take their names. (Camden 1335)

This etymology is not taken seriously today, but a possible connection with the Spanish ethnonyms is worth pursuing. It appears, however, that Artabri is a corrupt form of Arotrebae or Arrotrebae (Martinez 723).

In his Irish history, Ogygia (1685) Roderic O’Flaherty can make no sense of the name Velabri, which he declares to be as foreign to him in sound as the names of the Savage nations of America (O’Flaherty 23).

The Welsh scholar William Baxter, writing in the early 18th century, concurred with Camden’s analysis:

Vellabori: In Ptolemy, these are an Irish people next to the Southern Promontory in Munster, on the authority of Camden. From the British Bêl or Vêl Aber, ie Head of an Estuary. And I am inclined to think that the English name of that promontory Biar Head is a hybrid composition for Aber Head, which means the same thing. Also, in some sources of Ptolemy Ὀυελλέβοροι [Velleboroi] is written, or Ὀυελίβοροι [Veliboroi]. Each of these is surely corrupt. (Baxter 236)

Biar Head is an old English name for Mizen Head, which has frequently been identified with Ptolemy’s Southern Promontory (Ware & Harris 43).

In The Antiquities of Ireland (1654), the Irish antiquary James Ware wrote:

Velabri, a People, in some Copies called Vellibori. These People inhabited the northern Parts of Kerry; but whether they took their name- from the Iberi, a People in Spain, is a Point to be doubted. Orosius maxes the Luceni their neighbours on the Mouth of the Shanon. (Ware & Harris 44)

Ware’s 18th-century editor Walter Harris added a lengthy note to this summarizing the opinions of Camden and Baxter—his two favourite sources.

In 1789, another Irish scholar, William Beauford, added the following speculative contribution to the debate:

Ουλιβοροι [Veliboroi]. Edit. of Pal. has οικαι Ἐλλιβροι. Ware thinks them the inhabitants of the northern parts of Kerry; but the Romans here also denominated them from their headland, in Irish Beal Ibh Eiragh. They were the inhabitants near Kerry head. In the neighbourhood of which Orosius places the Lucanos, the ancient inhabitants of Lixnaw in the barony of Clanmorris in the county of Kerry. (Beauford 60-61)

Kerry Head is the southern headland at the end of the Shannon Estuary. Beauford’s Beal Ibh Eiragh must refer to the Iveragh Peninsula. Lixnaw is a village in the north of Kerry, but it is doubtful whether its name is related to Orosius’s Luceni.

In the early 19th century, the Irish historian Fr Charles O’Conor came up with a slightly different etymology for this ethnonym:

Velabri, in other codices Velibori—In Irish Siol-Ebir, clearly the Illiberi of Iberia, they dwelt in County Kerry. Orosius makes the Luceni their neighbours—“at the mouth of the river Scena” (O’Conor lvii)

I think it is safe to set aside this etymology. It is true that many tribes in Gaelic Ireland have names that begin with Síol or Síl, meaning seed, progeny, offspring, race. For example, the Síl nÁedo Sláine, the branch of the Uí Néill descended from Áed Sláine, High King of Ireland 598-604 CE. But Ptolemy’s Vellaboroi predate the Goidelic colonization of Ireland by several centuries. Their name is Celtic, but not Irish (ie Gaelic). O’Conor is also cavalier in his treatment of the initial sound. Is it v, s, or non-existent? These things matter.

In the late 19th century, Goddard Orpen of the Royal Irish Academy did not associate the Vellaboroi with any of the historical tribes of Ireland, being more interested in the neighbouring tribe mentioned by Orosius:

The Οὐελλάβοροι [Vellaboroi] (v. l. Οὐτέλλαβροι [Outellabroi]), whom Ptolemy places in the extreme S.W. corner of the island, are mentioned by Orosius (floruit circa 417 A.D.) in the following passage: [see translation above]. From this passage, which seems to have reference to the S.W. extremity of Ireland, thus agreeing with the position clearly assigned by Ptolemy to the Οὐελλάβοροι , I feel inclined to identify the ostium fluminis Scenæ (or in the parallel passage of the Pseudo-Æthicus, Sacanæ], not with the Shannon, as is usually done, but with the inbher Scéne of the bardic literature, i.e. with the great estuary now known as the Kenmare River. The Luceni of these writers might represent the later Luighne, a tribe-name now surviving in the baronies of Leyney in Sligo, and Lune in Meath. (Orpen 119)

Pseudo-Æthicus refers to the 7th- or 8th-century Cosmographia of uncertain authorship. The manuscript available for online viewing at Gallica has the reading sacerne, not Orpen’s sacanæ. In my opinion, it is unlikely that Orosius, writing around 417 CE, was referring to the Kenmare River when he wrote ostium fluminis Scenæ. As R A S Macalister has shown, it was much later that this expression was misinterpreted as a reference to the Kenmare River. Speaking of the framing story around which The Book of Invasions was constructed, he comments:

This production was a slavish copy, we might almost say a parody, of the Biblical story of the Children of Israel. The germ which suggested the idea to the writer was undoubtedly the passage in Orosius (I. 2. 81), wrongly understood as meaning that Ireland was first seen from Brigantia in Spain, where (ibid., § 71) there was a very lofty watch-tower. This suggested a reminiscence of Moses, overlooking the Land of Promise from Mount Pisgah: and the author set himself to work out the parallel, forward and backward. Incidentally Orosius gave trouble to Irish topographers, ancient and modern, by speaking of an Irish river Scena, setting them on a hunt for a non-existent Inber Scēne. As sc conventionally represents the sound of sh (compare the Vulgate Judges, xii, 6, where the Hebrew word shibbōleth is rendered scibboleth), we must pronounce this word as Shena, and it is then easily recognised as Orosius’ version of Sinann (genitive Sinna) or “Shannon.” (Macalister xxxi)

Conclusions

I believe that Eoin MacNeill was correct when he hypothesized that the Book of Leinster’s Fellubar is a reminiscence of Ptolemy’s Vellaboroi, and I think O’Rahilly and Counihan were correct when they suggested that Fellubar was a place name rather than a personal name. Counihan’s etymology, that Vellaboroi (or whatever the correct form was) meant ‘the very boastful people’, is perhaps a little too literal. Celtic tribes were usually named after an ancestral deity, so I am inclined to think that if there ever was a boastful speaker, it was this deity.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Martin Counihan, Researchgate (2019)

- Patrick S Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla: An Irish-English Dictionary, Irish Texts Society, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1904)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister, Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland, Part 1, Irish Texts Society, Volume 34, The Educational Company of Ireland, Ltd, Dublin (1938)

- John [Eoin] Mac Neill, Early Irish Population-Groups: Their Nomenclature, Classification, and Chronology, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Volume 29 (1911/12), pp 59-114, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1911-12)

- Eoin Mac Neill, Varia. I, Ériu, Volume 11, pp 130-135, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1932)

- Eugenio R Luján Martinez, The Language(s) of the Callaeci, e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies, Volume 6, Issue 1, Article 16, pp 714-748, The Center for Celtic Studies at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (2006)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Volume 1, Prolegomena, Pars I, John Seeley, Buckingham (1814)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 2, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Paulus Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, R P Pryne, Toronto (2015)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Pseudo-Æthicus, The Cosmography of Aethicus Ister, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Latin 9661

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel, Ptolemy’s Celtic Italy and Ireland: A Linguistic Analysis, in David N Parsons & Patrick P Sims-Williams (editors) Ptolemy: Towards a Linguistic Atlas of the Earliest Celtic Placenames of Europe, University of Wales, CMCS Publications, Aberystwyth (2000)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- River Roughty, County Kerry: © 2019 Google Maps, Fair Use

- Eoin MacNeill: Wikipedia, Public Domain

- Paulus Orosius: Anonymous Engraving, Codex of Saint-Epure (11th Century), Public Domain

- Sliabh Luachra, County Kerry: © John Finn, Fair Use

- The Tower of Brigantia, A Coruña, Spain: © Diego Delso, Creative Commons License

- Mizen head, County Cork: Wikimedia Commons, © Ent-ente, Creative Commons License

- Carrauntoohil, County Kerry: © Jim Barton, Geograph, Creative Commons License

Congratulations @harlotscurse! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPTo support your work, I also upvoted your post!

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit