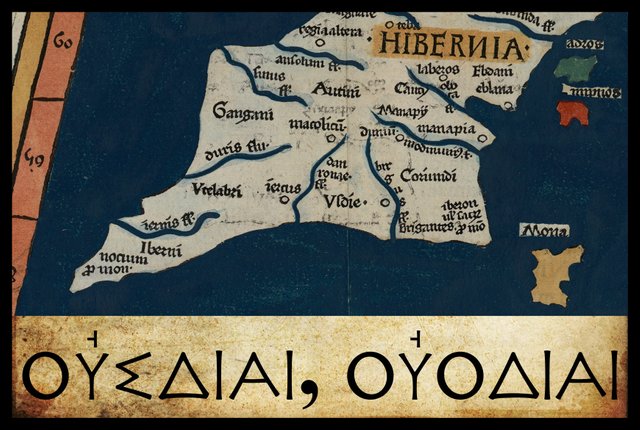

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the names and disposition of sixteen Irish tribes. The sixteenth and final tribe that we encounter are called Ousdiai (Latin: Usdiæ) or Vodiai (Latin: Vodiæ, Vodii). Ptolemy places these people beyond (ὑπερ [huper] + accusative) the Ivernoi, who occupy the midpart of Ireland’s south coast.

In his 1883 edition of the Geography, Karl Müller notes two variant readings of this ethnonym. In his 1838 edition of the Geography, Friedrich Wilberg records Müller’s critical form as a variant and chooses one of Müller’s two variants as his own critical form. In his edition of 1845, Karl Nobbe agrees with Wilberg’s choice of the critical form.

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Arg, N, V, X, Σ, Φ | Οὐσδιαι | Ousdiai |

| Most MSS | Οὐοδιαι | Vodiai |

| Ψ, ב | Οὐδιαι | Oudiai |

| Source | Latin |

|---|---|

| 4803 | Usdiæ |

Arg is the Editio Argentinensis, a printed edition based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

N refers to a pair of Latin manuscripts discovered by the Prussian geographer Konrad Mannert.

V is an edition of Ptolemy’s Geography published in Ulm in 1482 by Lienhart Holle, with the assistance of the cartographer Nicolaus Germanus Donis.

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is believed that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v–139r.

Φ, Σ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38, Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 and Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

ב is identified by Müller as Scorialensis Ω, I, 1. This is a manuscript in one of the libraries in the royal seat of El Escorial in Spain.

4803 is one of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. It is a Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803.

Critical Form

Müller selects Οὐσδιαι [Ousdiai] as the critical form even though it occurs in only five manuscript sources. Wilberg & Nobbe’s choice, Οὐοδιαι [Vodiai], is of much commoner occurrence. The third form, Οὐδιαι [Oudiai], can probably be dismissed as a simple transmissional error—some careless copyist accidentally dropped the third letter in this ethnonym. This variant is only attested by two sources.

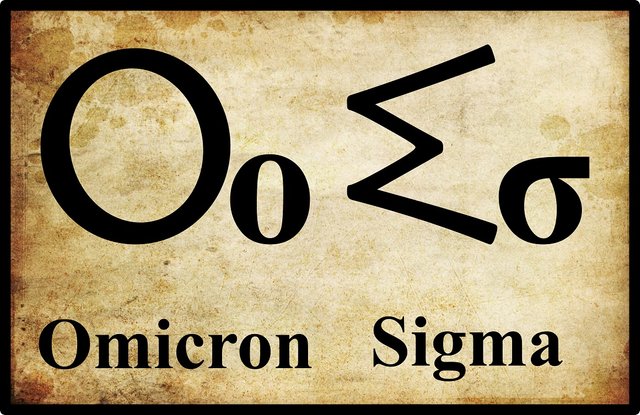

As for the other two readings, it is equally clear that somewhere along the line of transmission a copyist mistook -ο- [-o-] for -σ- [-s-] or vice versa. These two letters, omicron and sigma, do not resemble each other in Ptolemy’s Alexandrian script, but in the later Byzantine minuscule script they are quite similar, so the error probably crept in during the Middle Ages:

We came across the same confusion in an earlier article on the ethnonym Οὐολουντιοι [Volountioi]. Some manuscript sources record this tribal name as Οὐσλουντιοι [Ouslountioi]. In that case, the omicron was taken to be correct on linguistic grounds. It was also the commoner reading. Curiously, every manuscript that has Οὐσδιαι [Ousdiai] also has Οὐσλουντιοι [Ouslountioi]. Does this mean that we should reject Οὐσδιαι just as we rejected Οὐσλουντιοι ?

Why does Müller choose as the critical form a reading that is attested by only five manuscripts? Unfortunately, he does not say. Both readings are tenable. We know that Ptolemy used the digraph -ου- [-ou-] to represent both the diphthong [ou] and the semivowel -v- or [w], for which there was no longer a suitable letter in Greek. For example, in Ptolemy’s name for the river Boyne, Βουουινδα [Bououinda], the first -ου- is the diphthong, while the second is the semivowel: Bouwinda [Latin: Buvinda]. Ousdiai and Vodiai (or Wodiai) are both plausible readings. Perhaps we will be able to eliminate one of them on linguistic grounds.

A Note on Ptolemy’s Use of Breathings

In Celtic, v was pronounced like our modern semivowel [w], as it was in Classical Latin. In later forms of Irish, [v] and [w] are found, depending on the context and the dialect. As we have seen several times before in this series, Ptolemy used the Greek digraph ου [ou] to represent the Celtic letter v because the Greek letter digamma, which had formerly represented this sound, had fallen out of use (except as the numeral 6). T F O’Rahilly explained this practice in his Early Irish History and Mythology in connection with the Greek names for Ireland:

The name ’Ιέρνη, “Ireland”, had probably been picked up by the Massaliot Greeks, from merchants and from their Celtic neighbours, as early as the fifth century B.C. ... The digamma had disappeared from Ionic as early as the seventh century B.C.; and when Massaliot Greeks first heard the name Īvernā [Ireland], they presumably had no means of indicating the -v- and simply dropped it. Later the Greeks adopted the expedient of representing v in foreign names by ου ... We may take it that Pytheas [believed by O’Rahilly to be Ptolemy’s principal source for information about Ireland] retained the traditional name ’Ιέρνη ... whereas in dealing with other names previously unrecorded, we find him representing Celtic v by Greek ου, as for instance in ... Bouvinda [Βουουινδα] ... Ptolemy, or some near predecessor of his, modernized ’Ιέρνη into ’Ιουερνία [Ivernia] ... (O’Rahilly 41-42)

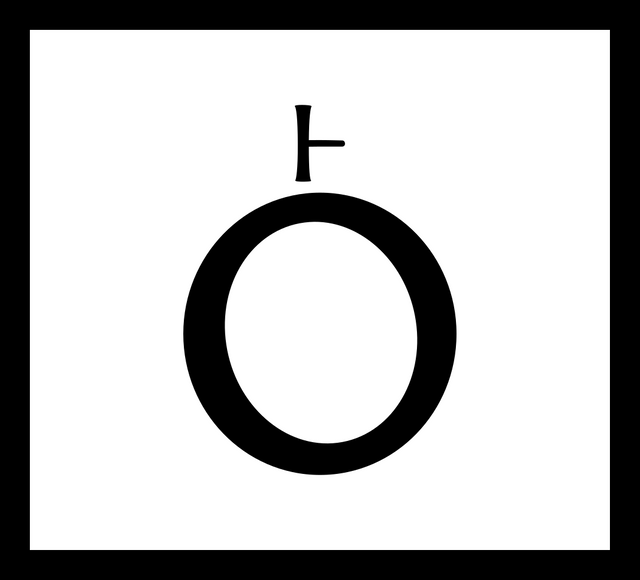

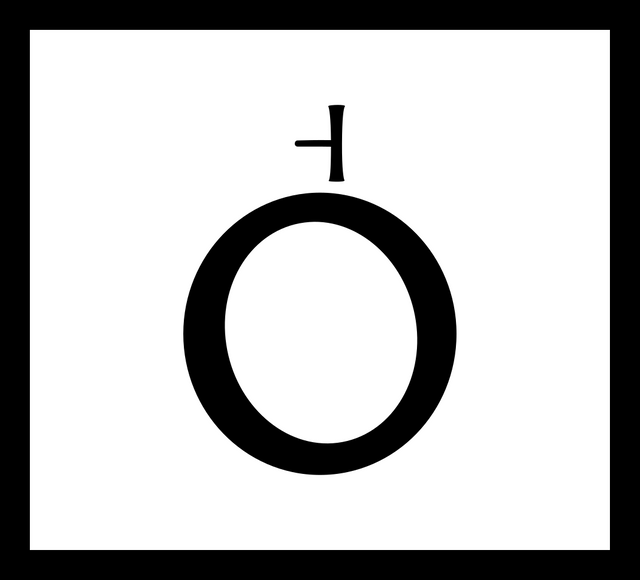

Once again I quote Amalia Gnanadesikan, the Technical Director for Language Analysis at the University of Maryland’s Center for Advanced Study of Language, on the use of diacritics in ancient Greek. In her book The Writing Revolution, she makes the following pertinent comment on the question of smooth and rough breathing in Ptolemy’s Alexandria:

In the process of accumulating and copying texts, the Alexandrian scholars began to show concern for matters of orthography. They found that at certain points the lack of a written form of [h] made for ambiguity. They noted that the Greeks living in Italy had been more free-thinking than the Athenians. While they had gone along with the adoption of the Ionic alphabet, they continued to write [h] by cutting the hēta in half and using ├. The Alexandrians adopted the Italian Greeks’ half H, but wrote it as a superscript on the following vowel, so that, for example,

was ho. Loving symmetry, they made the other half of H stand for the lack of an [h] sound before a vowel:

These diacritics came to be termed “rough breathing” (for [h]) and “smooth breathing” (for lack of [h]). Their use was for many centuries largely reserved for cases where ambiguity could arise without them. These marks later became ‘ and ’, so that ὁ was ho and ὀ plain o ... Only by the ninth century AD (well into the Byzantine period, AD 330–1453) did the use of breathing and accent diacritics become fully regular, with all vowel-initial words marked for “rough” or “smooth” breathing and all words marked for accent. (Gnanadesikan 220 ... 221)

I take these remarks to imply that Ptolemy probably only employed the diacritics for smooth and rough breathings in cases where the correct reading was not already obvious to the reader. In other words, he probably did not include the breathing in common Greek words, as its presence in such words was too well known to require inclusion. In the case of foreign toponyms and ethnonyms, however, he probably did include it. Hence we have Οὐσδιαι rather than Ουσδιαι.

Locating the Ousdiai (Vodiai)

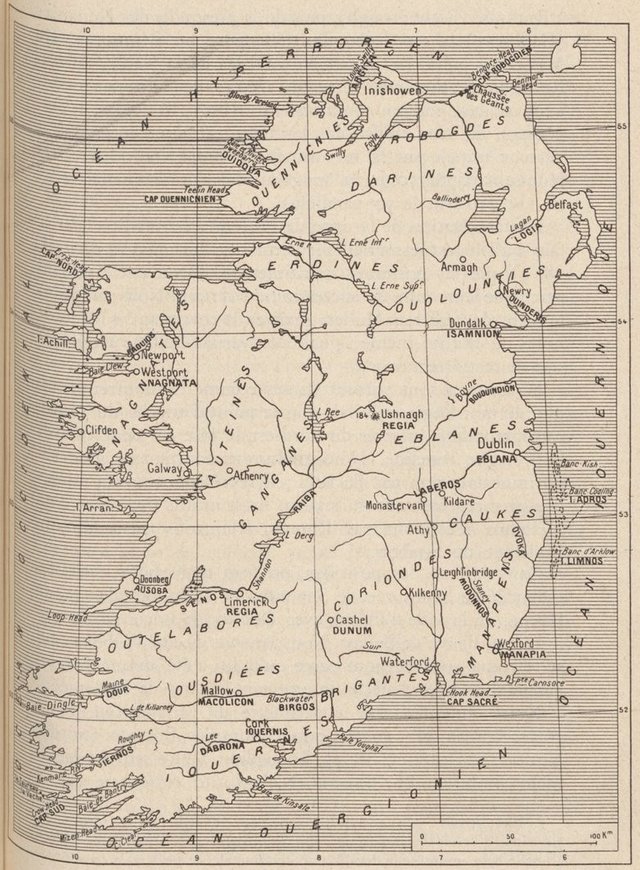

Where did the Ousdiai dwell? Ptolemy includes them in his enumeration of the tribes dwelling on the south coast of Ireland, but his language is somewhat ambiguous. Consequently, the Ousdiai appear in slightly different positions depending on whose map you consult. The French scholar André Berthelot placed them inland, to the north of the Ivernoi, which was my original understanding of Ptolemy’s text:

But contrast this with Nicholaus Germanus’s map at the top of this article, in which they are placed on the south coast between the Ivernoi and the Brigantes.

Ptolemy’s actual text reads (followed by a fairly literal translation after Freeman, p 75):

6 Παροικουσι δε την πλευραν μετα τους Οὐελλαβορους Ἰουερνοι, ὑπερ οὑς Οὐσδιαι και ἀνατολικωτεροι Βριγαντες.

6 The Ivernoi inhabit the coast after the Vellaboroi, above these [are the] Usdiai, and farther to the east [are the] Brigantes.

The Greek preposition ὑπερ [huper] is followed here by the accusative plural relative pronoun οὑς [hous]. According to Liddell & Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon, when ὑπερ takes the accusative, it means the following:

ὑπερ B. WITH ACCUS., expressing that over and beyond which a thing goes: I. of Place in reference to motion, over, beyond ... without such reference ... (Liddell & Scott 1608-1609)

This suggests that the Ousdiai dwell beyond the Ivernoi, which in this context would mean to the east of the Ivernoi. In an earlier article in this series I translated this passage as though ὑπερ were followed by the genitive plural, meaning: farther inland, or above, implying in this context to the north. That this was a mistake is suggested by Ptolemy’s use of the comparative degree ἀνατολικωτεροι, more eastern, which governs Brigantes, implying that the Ousdiai are to the immediate east of the Ivernoi, while the Brigantes are even farther to the east. If the Ousdiai were to the north of the Ivernoi and the Brigantes to the east of the Ivernoi, there would be no reason to use the comparative degree.

But now consider § 8, where Ptolemy enumerates the tribes that dwell on the east coast, starting with the Rhobogdioi in the extreme northeast of Ireland and ending with the Brigantes in the extreme southeast. His text reads:

6 Παροικουσι δε και ταυτην την πλευραν μετα τους Ῥοβογδιους Δαρινοι, ὑφ’ οὑς Οὐολοντιοι. ειτα Εβλαηιοι. ειτα Καυκοι, ὑφ’ οὑς Μαναπιοι. ειτα Κοριονδοι ὑπερ τους Βριγαντας.

6 And after the Rhobogdioi this coast is inhabited by the Darinoi, below whom are the Volontioi. Then the _Eblanioi. Then the Kaukoi, below whom are the Manapioi. Then the Koriondoi over the Brigantes.

Here again, ὑπερ takes the accusative, τους Βριγαντας, but the sense seems to be clearly to the north of the Brigantes—certainly not beyond the Brigantes, as it is the Brigantes who lie beyond the Koriondoi.

In this paragraph, it appears that Ptolemy is using the prepositions ὑπερ [over] and ὑφ’ [under] to describe positions on a map: namely, north of and south of respectively. But according to Liddell & Scott, this sense would take the genitive case, not the accusative:

ὑπερ A. WITH GENIT., which expresses that over which something is or happens. I. of Place, over; 1. in a state of rest, over, above (Liddell & Scott 1608)

I will return to this question in the following article, when I wrap up Ptolemy’s discussion of the tribes of Ireland.

John Rhys

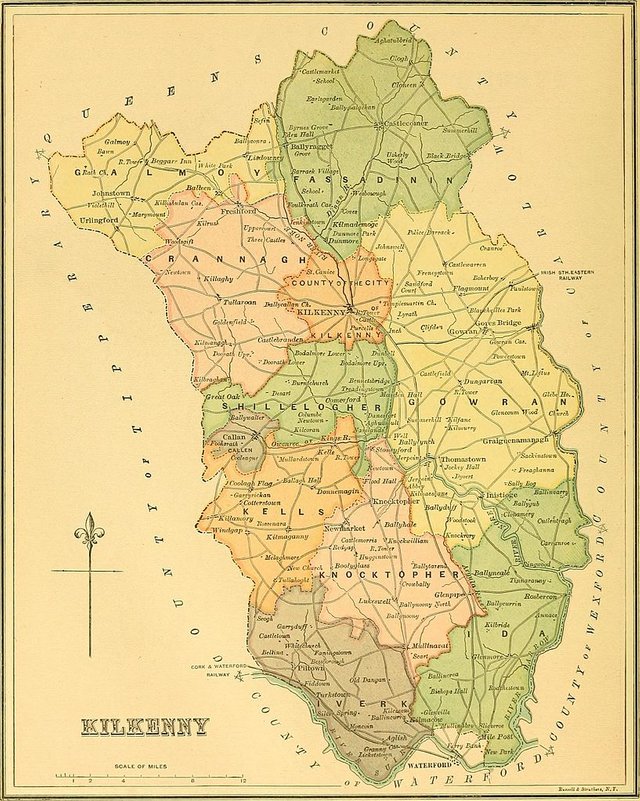

The Welsh historian John Rhys was the first to suggest that Ptolemy’s Ousdiai were the ancestors of the historical sept known as the Osraige [Ossory]. In late medieval times, Osraige was a powerful kingdom between Leinster and Munster. Its territory corresponded roughly to County Kilkenny and the western half of County Laois, with the Barrow and Suir as two of its borders. For most of its history, Osraige was considered a part of Munster, but in the 9th century, when its king Cerball mac Dúnlainge was one of the most powerful men in Ireland, it was formally ceded to Meath and the High King of Ireland Máel Sechnaill I:

Osraige, a name Anglicised Ossory: it is now borne by a diocese containing approximately the county of Kilkenny and Queen’s [Laois]; but the ancient people of the Ossorians laid claims to other districts such as the barony of Iffa and Offa East on the Suir, in the county of Tipperary. The name Osraige involves, like a great many other Irish tribal names, the syllables rige or raige, now written raighe or raidhe, as in Beanntraighe “Bantry,” Calraighe “Calry,” and others. Thus the distinctive portion of the name Ossory is the first syllable oss or os, which according to the laws of Irish phonology may be the representative of ods, ots, osd, or ost, as a dental with s becomes assimilated to that sibilant [see Thurneysen § 155]. So there is no difficulty in the way of our identifying the name in question with that of Ptolemy’s Οὐσδίαι “Usdiae,” which according to Müller is the best reading of the manuscripts. Ptolemy divides the whole of the South of Ireland between three peoples, whom he calls Ἰουέρνιοι, Οὐσδίαι , and Βρίγαντες. The first mentioned were the Ivernii or Erna of Munster, who appear at that time to have had most of that province, while the Brigantes occupied the south-east as far as Carnsore Point. Thus the Usdiae must have been posted between them, occupying the territory of the Osraige. Now the Irish version of Nennius speaks of the race of the Leinster Faelchú or Wolf, in Ossory, as the fourteenth wonder of Ireland. For the men of that race were believed to assume the form and nature of wolves whenever they pleased. This seems to mean among other things that the Men of Ossory regarded the wolf as their totem, and it is some such a state of things probably that suggested one of the Irish words for a wolf, namely mac tíre “the son of the land,” as though that wild beast was treated as the real autochthon of the country. In any case one cannot be surprised to find among the chiefs of Ossory in the seventh and eighth centuries men called Faelan and Faelchar from fael “a wolf.” Should the view, here suggested prove tenable, I should regard the oss of Ossory and Ptolemy’s Οὐσδίαι as derived from a Pictish word related to the Basque otso “a wolf,” whence otso-gizon “loup-garou,” or wolf-man. (Rhys 349-350)

Note that Rhys understands Ptolemy to have located the Ousdiai on the south coast, between the Ivernoi and the Brigantes. The historical kingdom of Osraige was inland, but the Ousdiai need not have remained in the territory that Ptolemy assigned to them—wherever that was.

As for Rhys’s Basque etymology, I find it plausible. The Basques of the historical period were possibly the descendants of a pre-Indo-European people, who inhabited parts of western Europe during the Ice Age. When the earliest Indo-Europeans migrated from the east into western Europe after the Ice Age, they would have interacted with these people and perhaps even interbred with them. It is only to be expected that they would have picked up some words from them and brought these words to Ireland and Britain.

Goddard Orpen

In 1894, Goddard Orpen recycled and endorsed Rhys’s conjectures:

I should suppose that [the] territory [of the Ivernoi] extended along the south coast from Waterford to perhaps Kinsale, and that they were separated from the Οὐσδίαι by the river Suir. For this last-mentioned tribe it will be observed that Müller selects the form Οὐσδίαι (Usdiæ) as the best, though some MSS. read Οὐοδίαι or Οὐδίαι. This reading has recently suggested to Professor Rhys, that the well-known tribe or group of tribes called in Irish Osraighe or Osraidhe (Ossory) was intended. The distinctive parts of the two names may be equated, while raidhe or raighe in the Irish name is a mere termination (perhaps indicating descent like the Greek -ιδης [-idēs]) and is common to many tribal names. It would naturally be replaced by a Greek termination. The remaining os or oss would represent an early osd, ost, ods, or ots, in which combinations the dental, according to the laws of Irish phonology, would become assimilated to the sibilant. Ptolemy appears to place the Οὐσδίαι in the counties of Tipperary and Kilkenny, and this agrees with what is stated to have been the early position of Osraighe between the Barrow and the Suir. The town called Μακόλικον [Makolicon] was probably in this territory, and may possibly have been the Rock of Cashel, which must always have been an important stronghold. Professor Rhys, in the passage quoted, where he is tracking out non-Aryan elements in the Celtic tongue, goes on to refer to the race of the Leinster Faelcu or wolf in Ossory, mentioned in the Irish Nennius and in Giraldus, and suggests that the oss of Ossory, and Ptolemy's Οὐσδίαι “may be derived from a Pictish word related to the Basque otso, a wolf, whence otso-gizon loup garou or wolf-man.” Professor Rhys goes on to notice how frequently the names Faelan and Faelcair appear among the chieftains of Ossory in the seventh and eighth centuries. He might have added St. Faelcu, or Aelcu, son of Faelcair King of Ossory, mentioned by Mac Firbis in his list of certain Bishops of Erinn. O’Huidhrin, too, mentions “O’Faolain of manly tribe” in Magh Lacha, a plain in the barony of Kells, Co. Kilkenny. Indeed examples of the name in this district might easily be multiplied. (Orpen 122-123)

The prominence of the wolf in Ossorian names is certainly a curious element, which Rhys’s hypothesis explains admirably.

Eoin MacNeill

A few years later, the Irish historian Eoin MacNeill also suggested that there could be a connection between Ptolemy’s Ousdiai and the historical Osraige, but he was a little less confident than Rhys and Orpen:

The close correspondence between the territory of Osraige (diocese of Ossory, but anciently also extending much farther westward) and the place assigned by Ptolemy to the Ousdiai makes it likely that the names also are closely associated (Osse -rge = *Osdia-rígion? Should we not expect Uisserge?). (MacNeill 67)

O’Rahilly

In his Early Irish History and Mythology (1946), T F O’Rahilly was not willing to commit himself to any one reading or etymology. Instead, he merely called into question Rhys’s hypothesis:

Usdiae, or Vodiae, or Udiae. Rhys and others have sought to connect their name with that of the Osraige; but it is difficult to establish the connexion. Irish tradition derives Osraige from os, ‘deer’, < *uksos. The Os in Os-raige was doubtless one of the designations of the ancestor deity, and was possibly a distinct word from os, ‘deer’. Compare the mythical Cú Oiss, who is represented as (1) son of Nuadu Find Fáil, in the pedigree of Éremón’s descendants, R 137 b 25, and (2) son of Nuadu Argatlám, and ancestor of the men of Munster (the Eóganacht), R 140 b1, 148 b 27 (and cf. 154 b 23). (O’Rahilly 10)

Roman Era Names

More recently, the contributors to the etymological website Roman Era Names have opted for the variant reading Ουοδιαι [Vodiai, Wodiai] as the correct form and do not even mention the Osraige:

Ουοδιαι (or Ουσδιαι) (Wodiai or Usdiai 2,2,7) lived in the south-east. Their name most likely came from PIE *wat- ‘insane, passionate’, whose descendants include OE wod ‘crazy’, OI faith and Latin vates ‘seer’, the Norse god Wotan/Odin, etc. Maybe they had energetic Druids.

T F O’Rahilly often mentions how fond Celtic tribes were of pluralizing the name of their ancestral deity in order to create a tribal name, ie an ethnonym (O’Rahilly 148). It makes sense, therefore, that Ουοδιαι was derived from the name of a goddess Ουοδια, a female counterpart, perhaps, of the Teutonic Woden.

Martin Counihan

The independent researcher Martin Counihan has reverted to Rhys’s Osraige hypothesis, adopting the form Usdiae. He is quite confident that this hypothesis is correct, but he has come up with a novel etymology that dispenses with Rhys’s Basque elements:

Between the provinces of Leinster and Munster was the once-extensive kingdom of the Osraige which is known in English as Ossory and whose name remains on the map at the small town of Borris-in-Ossory. These were the people whom Ptolemy recorded as the Usdiae.

The root of the name is probably the preposition which in Old Irish was ós, or occasionally úas, meaning “above”, or “in front of” or “on top of”, parallel to the Latin post (but with the loss of the consonant p common to all the Celtic languages). So, the tribal name meant something like “those above” or “those beyond”. But the exact meaning is elusive: beyond what? Beyond the coast, perhaps, and beyond the rivers Suir and Barrow, which run into Waterford harbour?

The Usdiae or Osraige bring to mind the Osismii, a powerful Gaulish tribe located in the north-west of the Armorican peninsula. The name of the Osismii has an uncontroversial meaning in Gaulish: it comes from the superlative form of the preposition mentioned above, and can be translated as “those most beyond”, or “the furthest”, an appropriate name for people living on one of Europe’s westernmost peninsulas. (Counihan 8)

I can’t say that I find any of this very compelling, but nor can I refute it.

Earlier Scholarship

In the 16th century, the English antiquarian William Camden grouped Ptolemy’s Ousdiai (Vodiai) and Koriondoi together, as though these were two names for the one people:

Vodiæ or Coriondi Beyond the Iberi, dwelt the Ουδίαι in a large Tract; who are call’d also Vodiæ and Udiæ: a resemblance of which name remains very clear in the Territories of Idou and Idouth; as there doth of the Coriondi in the County of Cork, which borders upon them. These People inhabited the Counties of Cork, Tipperary, Limerick, and Waterford. (Camden 1337-1338)

Camden’s territories of Idou and Idouth must refer to Idough, or, in Irish, Uí Duach, a territory (and its ruling family) in the northeast of Osraige, corresponding to the later barony of Fassadinin. Idou may also refer to the barony of Ida in the southeast of the county:

The Uí Duach, or Descendants of Duach, were probably named for the father of Feradach Finn, who was the King of Osraige in the late 6th century. This sept is, therefore, much too recent to have anything to do with Ptolemy’s Ουδίαι [Oudiai].

In the 17th century, the Irish antiquary James Ware followed Camden in treating the Ousdiai (Vodiai) and Koriondoi as the same people:

Coriondi and Udiæ, Vodii, or a People so called. They antiently were planted in the Countries now called the Counties of Cork, Tipperary and Limerick. Cork (Corcagia) a City of the Coriondi, seems to discover itself in the Name Coriondi. Whether these Coriondi were a Colony from the Coritani of Britain is very doubtful; and yet in Truth their Names are not much unlike. (Ware & Harris 38)

I have no idea how these early scholars came to confuse the Ousdiai and the Koriondoi. Ptolemy includes the latter among the tribes on the east coast, and the former among those of the south coast.

In the early 18th century, the Welsh scholar William Baxter devised a different etymology for this ethnonym, choosing Οὐοδιαι [Vodiai] as the critical form. Like me, he understood Ptolemy’s text to mean that the Vodiai dwelt in the interior of the island:

Vodiae In Ptolemy, these are an Irish people, inland inhabitants of Munster, evidently, Foresters, as you might say in the Britannic language, or Acting among the Forests, and through this ancient form to give rise to Of Irish Birth or Ἀυτοχθόνων [Autochthōn]; for Üydhieu or Güydhieu is expressed today by the Britons as Forests. (Baxter 253)

In the middle of the 18th century, the Irish antiquary Walter Harris, while editing and translating the complete works of James Ware, added the following comment of his own to Ware’s analysis of this ethnonym:

The Vodii, according to Baxter have taken their Name from their Situation in a woody Country; that that the British word, Uydhieu or Guydhieu denotes Woods. But I cannot agree with him that they were a Mediterranean [ie inland] People of Munster, being placed by Ptolomey on the Coast South of the Coriondi. Nor is Camden’s Conjecture very satisfactory, who thinks the Resemblance of the Name Vodii remains clear in Idou or Idouth. Whereas Idough was a noted Territory comprehending the Modern Barony of Fassaghdining in the County of Kilkenny, and is very far removed from the Vodii on the south Coast of the County of Cork. (Ware & Harris 38-39)

Again, we have the curious juxtaposition of the Vodiai and the Koriondoi. These early scholars must have been using a corrupt edition of the Geography.

In his Dissertations on the History of Ireland of 1766, Charles O’Conor treated his readers to the following curious analysis:

Some Time before the Birth of Christ, the Ernaidhs of Ulster (the Race of Olioll Aron) obtained great Power in Munster, under their Leader Deaghaidh, who afterward became King of the Province. His Posterity succeeded to his Power, in West-Munster particularly, and were well known by the Denomination of Clanna Deaghaidh and Ua-Deaghaidh. A Tribe of these Ua-Deaghaidhs were planted on the South Coast near Dun-Kermna. There Ptolomey places them; and, as in the usual Manner of the antient Scots, (who suppressed most of the Consonants in the Pronunciation) these Ua-Deaghaidhs were pronounced Uadaei; and they are not very improperly called Vodii, or Vedii by that Geographer. (O’Conor 177)

Dún Cermna is commonly placed on the Old Head of Kinsale in County Cork (though we saw in an earlier article that it might be better sought at Dunmore East in County Waterford).

Ua Deaghaidh, or O’Dea, are the descendants of a certain Deaghaidh, who is alleged to have lived in the late pre-Christian or early Christian era, during the reign of his brother Duach Dallta Deadhadh. According to The Annals of the Four Masters, Duach Dallta Deadhadh reigned from AM 5031-5041, or 169-159 BCE (O’Donovan 87). The Book of Invasions synchronizes his reign with that of Ptolemy XII Auletes (Neos Dionysos), the Macedonian ruler of Egypt from 80-58 BCE and 55-55 BCE (Macalister 297). Geoffrey Keating splits the difference and places him between 120 and 110 BCE (Keating 183, 222-237).

O’Conor’s hypothesis is untenable if we accept that Ptolemy’s data on Ireland goes back to the 4th century BCE, as O’Rahilly has argued (O’Rahilly 39-42). Nevertheless, his conjecture has received some support from later scholars—for example, Owen Connellan and Philip Mac Dermott, in their annotated translation of the latter part of The Annals of the Four Masters (Connellan & Mac Dermott 393).

In the late 18th century, the Irish scholar William Beauford also chose Οὐοδιαι [Vodiai] as the correct spelling of this ethnonym:

Οὐοδιαι: Ware makes these the ancient inhabitants of the counties of Cork, Limerick and Tipperary. The ancient name of this district is lost; they were probably the inhabitants of Corcaluighe, containing the southern parts of the present county of Cork. (Beauford 63)

Corcu Loígde was a petty kingdom in the west of County Cork, corresponding roughly to the baronies of Bear, Bantry, West Carbery and East Carbery. Beauford placed the Ivernoi in Iveragh (in the extreme southwest of the country), so he evidently regarded the Vodiai as a coastal people, who dwelt to the east of the Ivernoi.

Other early scholars, such as Roderic O’Flaherty and Fr Charles O’Conor, had nothing to offer concerning these people, aside from mentioning them.

Conclusions

Weighing up the evidence on all sides, I still find it impossible to choose between the two principal readings of this ethnonym: Ousdiai and Vodiai. The former would allow one to connect these people with the Osraige, who dwelt in historical times in roughly the same part of the country as Ptolemy’s tribe. On the other hand, Vodiai sounds more legitimate as the name of a Celtic tribe, albeit one which has left no trace in our native records, and it is more frequently attested in the manuscript sources.

Note that we can always adopt Ουοδιαι [Vodiai] as the correct form, and dispense with any connection between the Ptolemaic tribe and the historical Osraige, whilst at the same time retaining Rhys’s Basque etymology to explain the prominence of the wolf motif in Ossorian nomenclature. Perhaps this is the safest course to take.

There is also the unresolved question of where to place the Ousdiai (Vodiai): Inland, to the north of the Ivernoi : Or on the coast, to the east of the Ivernoi?

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- André Berthelot, L’Irlande de Ptolémée, in Revue Celtique, Volume 50, pp 238-247, Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, Paris (1933)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Owen Connellan, Philip Mac Dermott, The Annals of Ireland: Translated from the Original Irish of the Four Masters: With Annotations by Philip Mac Dermott and the Translator, Bryan Geraghty, Dublin (1846)

- Martin Counihan, Researchgate (2019)

- Patrick S Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla: An Irish-English Dictionary, Irish Texts Society, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1904)

- Philip Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World, The University of Texas Press, Austin TX (2001)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Geoffrey Keating, Patrick S Dinneen (translator & editor), The History of Ireland, Volume 2, Irish Texts Society, Volume 8, David Nutt, London (1908)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister (translator & editor), Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland, Part 5, Irish Texts Society, Volume 44, The Educational Company of Ireland, Dublin (1956)

- John [Eoin] Mac Neill, Early Irish Population-Groups: Their Nomenclature, Classification, and Chronology, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Volume 29 (1911/12), pp 59-114, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1911-12)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Dissertations on the History of Ireland to which is subjoined a Dissertation on the Irish Colonies Established in Britain with Some Remarks on Mr Mac Pherson’s Translation of Fingal and Temora, George Faulkner, Dublin (1766)

- Fr Charles O’Conor, Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Volume 1, Prolegomena, Pars I, John Seeley, Buckingham (1814)

- John O’Donovan (translator, editor), Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland, By the Four Masters, Second Edition, Volume 1, Hodges, Smith, and Co, Dublin (1856)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 1, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- John Rhys, The Inscriptions and Language of the Northern Picts, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Volume 26, pp 263-351, Neill and Company, Edinburgh (1892)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- The Kingdom of Osraige: Erigena (creator), Public Domain

- Brandon Hill: Sarah777 (photographer), Public Domain

- Inistioge Bridge over the River Nore, County Kilkenny: © Humphrey Bolton, Creative Commons License

- St Mark’s Church, Borris-in-Ossory, County Laois: Sarah777 (photographer), Public Domain

- The Baronies of County Kilkenny: John Savage, Picturesque Ireland, Thomas Kelly, New York (1885), Public Domain

- The Baronies of County Cork: John Savage, Picturesque Ireland, Thomas Kelly, New York (1885), Public Domain

- County Waterford (Near Dungarvan): Jorge1767 (photographer), Public Domain