In the final section of his description of Ireland—Geography, Book 2, Chapter 2, § 10—Claudius Ptolemy records the names and positions of nine islands, five of which lie to the north of Ireland and four to the east. These comprise a curious collection, as surprising for its inclusions as for its exclusions:

Ptolemy names nine islands in all, but only two or three of these can be regarded as properly belonging to Ireland. (O’Rahilly 2 fn 4)

Ptolemy’s Text

10 Above Ivernia lie the islands known as the Aiboudai, five in number, of which the most westerly is called:

| Greek | Latin | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Αἰβουδα | Ebuda, Æbuda | Aibouda | 15° | 62° 00' |

Nearest to this, to the east:

| Greek | Latin | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ὁμοίως Αἰβουδα | item Ebuda, item Æbuda | likewise Aibouda | 15° 40' | 62° 00' |

Then:

| Greek | Latin | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ῥικινα | Rhicina | Rhikina | 17° | 62° 00' |

Then:

| Greek | Latin | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Μαλαιος | Maleus | Malaios | 17° 30' | 62° 30' |

Then:

| Greek | Latin | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ἐπιδιον | Epidium | Epidion18° 30' | 62° 00' |

And to the east of Ivernia lie these islands:

| Greek | Latin | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Μοναοιδα | Monaœda | Monaoida | 17° 40' | 61° 30' |

| Μονα νησος | Mona insula | Mona Island | 15° | 57° 40' |

| Ἀδρου ἐρημος | Adru insula deserta | Adrou, uninhabited | 15° | 59° 30' |

| Λιμνου ἐρημος | Limnu insula deserta | Limnou, uninhabited | 15° | 59° 00' |

Ptolemy’s Islands

Ptolemy’s nine islands of Ireland represent a special class of geographical objects that should, in my opinion, be distinguished from the thirty-one locations and sixteen tribes he places on the mainland.

Firstly, most of them—at least seven—have been identified with modern counterparts with some degree of confidence, as their names correspond closely to their current or recent Celtic toponyms. This is in stark contrast to the vast majority of Ptolemy’s toponyms on the mainland—Oboka, Laberos, Ausoba, etc—which don’t bear much resemblance, if any at all, to any of the better-known names of the places to which these toponyms are supposed to refer.

Secondly, most of these islands are not truly Irish. We have already quoted T F O’Rahilly to this effect above. Philip Freeman concurs:

Several if not most of the islands associated here with Ireland are actually closer and more historically tied to Britain. (Freeman 82)

As early as the 17th century, the Irish antiquary James Ware recognized this salient fact and included only three of the nine islands in his alphabetical survey of Ptolemy’s Ireland:

But many of these are at this Day reckoned among the Islands of Great Britain, to which they are nearer, as the Ebudæ, Maleos, Epidium, Mona-æda and Mona; and for that Reason we have omitted them in this Inquiry. (Ware & Harris 45)

Five of Ptolemy’s islands belong indisputably to Britain, and one other—if it is correctly identified with the Isle of Man—is closer to Britain than it is to Ireland. Only three of Ptolemy’s islands are truly Irish—although one of these is actually a peninsula. What’s more, the names that Ptolemy gives to these three indisputably Irish islands bear a close resemblance to Gaelic names of later times.

Why, then, does Ptolemy assign these islands to Ireland? As far as the six most northerly islands are concerned, I believe the reason lies in the misalignment of Ptolemy’s map of Scotland. As is well known, Ptolemy depicts Scotland with its long axis lying west-east instead of south-north. One of the consequences of this is that the islands that actually lie off the west coast of Scotland appear to lie off the north-east corner of Ireland. So it is not surprising that Ptolemy assigns them to Ireland. As for the remaining three islands, two of these are correctly identified as Irish. So there is only one island—Mona, or Anglesey—which has absolutely no place in a list of Irish islands.

From these incontrovertible facts I am going to argue that Ptolemy’s principal source for these nine islands was the same one from which he took his geographical data on Britain, and not the principal source he drew on for his description of mainland Ireland. Curiously, Walter Harris, who edited the writings of James Ware, made a similar conjecture in a note appended to the above quotation from Ware:

Another Thing to be observed is, that many of the preceding Names are drawn from British Fountains [ie Sources], and probably have been given them by British Sailors frequenting the Irish Coasts ... (Ware & Harris 45)

In Part 1 of this series, and again in several subsequent articles, I have alluded to T F O’Rahilly’s argument that Ptolemy’s Ireland describes the country as it was about half a millennium before Ptolemy’s time. O’Rahilly has proved beyond dispute that Ptolemy’s information on Ireland is seriously out of date, and does not correspond to the situation as it was in the middle of the 2nd century CE, when he compiled his Geography:

As the foregoing discussion has shown, the most striking feature of Ptolemy’s account of Ireland is its antiquity. The Ireland it describes is an Ireland dominated by the Érainn, and on which neither the Laginian invaders nor the Goidels have as yet set foot. The language spoken in it was Celtic of the Brittonic type (p. 17). The form Rēgiā, for *Rīgiā (p. 14) likewise suggests an early date, before IE. ē had been assimilated to ī in Celtic. [Footnote 1: Note also _Auteini, in which the ei (found in nearly all the MSS. of Ptolemy) may represent IE. ei, which later became ē in Celtic.] (O’Rahilly 39-40)

O’Rahilly surmised that Ptolemy’s principal source for his Irish data was Pytheas of Massalia, who is thought to have visited Ireland and Britain around 325 BCE, or perhaps slightly later. Only a few fragments of his writings survive, but some of these suggest a detailed and intimate knowledge of Britain:

Pytheas (fl. 310-306 B.C.) ... The early-fifth-century Himilco may deserve recognition as the first recorded Mediterranean voyager to the area of the British Isles, but the late-fourth-century travels of Pytheas northward beyond the Pillars of Hercules were more extensive, though only slightly better documented. Although this explorer from Massalia does not mention Ireland or the Irish in the few fragments attributed to him, it is probable that he at least saw the island, even if he did not actually set foot there. His report of the total coastline of Britain, as well as other descriptive details from throughout the island, may imply an extensive reconnaissance if not a circumnavigation of Britain. (Freeman 33)

If Pytheas did carry out an extensive reconnaissance of Britain, it stands to reason that he probably also did so with regard to its sister isle.

In contrast to his description of Ireland, Ptolemy’s Britain is an accurate portrayal of that island as it was in Ptolemy’s own time (about 150 CE). The Dumnonii—or Damnonioi as Ptolemy calls them—who were closely related to the Laginians of Ireland (O’Rahilly 93-94), are recorded in his description of Britain. It is inconceivable that they had not also colonized Ireland by Ptolemy’s day. In fact, the Lagin were then so prevalent in the southeast quarter of the island—the quarter closest to the European mainland—that this part of the country is still named for them today (Leinster, from the Irish Cóiced Lagen, or Fifth of the Lagin). It is inconceivable that Ptolemy should have omitted all mention of them from his description of Ireland but included them in his description of Britain.

The omission of other notable and indisputably Irish islands from Ptolemy’s list also argues a British source for his information. One might ask where are Achill, the Aran Islands, Clew, Aranmore, Tory, the Blaskets or the Great Island in Cork Harbour?

Note that four of Ptolemy’s islands share the same longitude, while four share the same latitude. This is a suspiciously artificial arrangement. It is possible that Ptolemy had little concrete information on the precise locations of these islands. He knew that three lay off the east coast of Ireland and six off the north-east corner, but little else. This could also explain how he came to associate them with Ireland rather than with Britain.

In the following nine articles we will take a closer look at each of Ptolemy’s Irish islands in turn.

References

- Patrick S Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla: An Irish-English Dictionary, New and Revised Edition, Irish Texts Society, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1927)

- Philip Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World, The University of Texas Press, Austin TX (2001)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

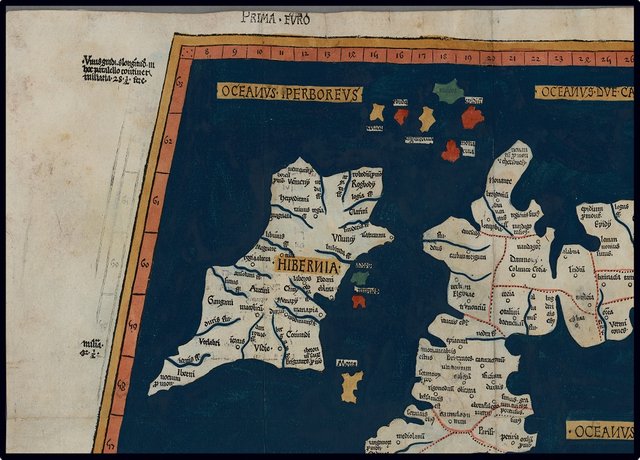

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Rathlin Island: © Brian O’Neill, Creative Commons License

- The Isle of Man: © Copyright Independent Hostels UK 2019, Fair Use

- Pytheas: Auguste Ottin (sculptor), Marseille, © Rvalette, Creative Commons License

- Lambay Island: © Joseph Mischyshyn, Creative Commons License

- Howth Peninsula, Dublin: © Robert Linsdell, Creative Commons License