In the final article in this series on Claudius Ptolemy’s map and description of Ireland—Geography, Book 2, Chapter 2—I hope to tie up a few loose ends and take my leave of the great Alexandrian geographer.

Ptolemy’s Irish Sources

In the preceding article I concluded that Ptolemy compiled his description of Ireland using two principal sources, neither of which is extant:

Marinus of Tyre’s map of Ireland (circa 120 CE), which was probably no more than a rough outline of the island, indicating its size, shape and location.

Pytheas of Massalia’s account of Ireland (circa 325 BCE), which probably comprised no more than a periplus of coastal features and an itinerary of inland settlements.

I do not have much confidence in the coordinates Ptolemy assigns to the geographical features of Ireland.

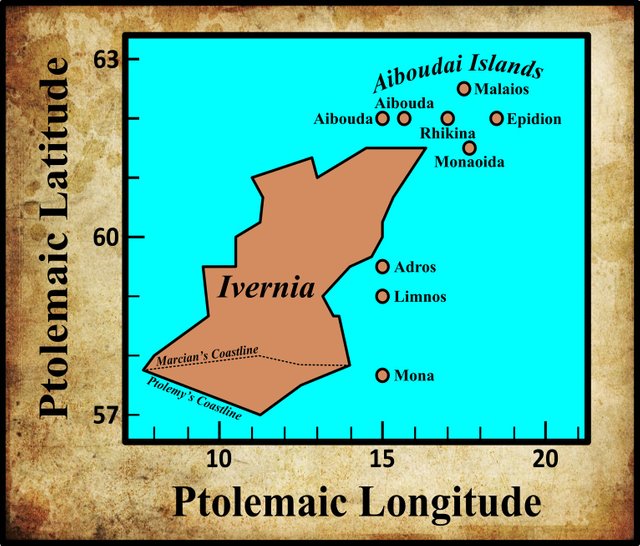

Ireland’s Islands

As I pointed out in an earlier article, the list of nine islands that Ptolemy appends to his description of Ireland was clearly compiled from a catalogue of islands lying to the west of Britain. Only two or three of these islands are genuinely Irish. Ptolemy’s source for this list was contemporary (or fairly recent), in contrast to his source for Ireland’s mainland features, which was several centuries out of date.

Ireland’s Headlands

Ptolemy records five Irish headlands:

| Greek | Latin | English | Modern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Βορειον ακρον | Boreum promontorium | Northern Cape | Bloody Foreland? |

| Ουεννικνιον ακρον | Vennicnium promontorium | Vennicnian Cape | Banba’s Crown |

| ‘Ροβογδιον ακρον | Rhobogdium promontorium | Robogdian Cape | Fair Head |

| ‘Ιερον ακρον | Sacrum promontorium | Sacred Cape | Carnsore Point |

| Νοτιον ακρον | Australe promontorium | Southern Cape | Cape Clear? |

Curiously, three of these have purely Greek names, while the other two are each named for a local tribe. Did the native Irish not consider their headlands worthy of being named? Or were there native names for these headlands, which, for one reason or another, were replaced by foreign names?

The Historical Context

According to T F O’Rahilly, Ptolemy’s geography of Ireland depicts the country as it was around 325 BCE, when the island was visited by Pytheas of Massalia—about half a millennium before Ptolemy’s day. O’Rahilly’s model—which is consistent with both the Short Chronology and our native traditions—postulates four principal Celtic colonizations of Ireland:

(1) The Cruthin (Priteni), after whom these islands were known to the Greeks as ‘the Pretanic Islands.’ In early historical times they preserved their individuality best in the North of Britain, where they were known to Latin writers as Picti.

(2) The Builg, commonly called Fir Bolg, and also known as Érainn (Iverni). Their name (*Bolgī) identifies them with the Belgae of the Continent and of Britain. According to Irish tradition they were of the same stock as the Britons; and their own invasion-legend tells how their ancestor Lugaid came from Britain and conquered Ireland.

(3) A group of tribes whom we may call the Laginian invaders, and who included the Lagin, the Domnainn and the Gálioin. The two latter tribes were admittedly pre-Goidelic, and, partly for this reason, their names fell into disuse; but under the name Lagin those of the invaders that had held on to their conquests in Mid and South Leinster were provided with a fictitious Goidelic pedigree. According to their own invasion-legend they were in origin Gauls, who invaded Ireland from Armorica [Brittany]. Their conquest of Ireland was but a partial one, confined for practical purposes to considerable parts of Leinster and Connacht.

(4) The Goidels, the latest of the Celtic invaders, and the only Q-Celts among them. They reached Ireland direct from Gaul, and their arrival cannot have been much anterior to the extinction of Gaulish independence (50 B.C.). (O’Rahilly 15-17)

For the most part, I accept this model. O’Rahilly believes that Pytheas visited the island before the third colonization:

[The] most striking feature of Ptolemy’s account of Ireland is its antiquity. The Ireland it describes is an Ireland dominated by the Érainn, and on which neither the Laginian invaders nor the Goidels have as yet set foot. (O’Rahilly 39-40)

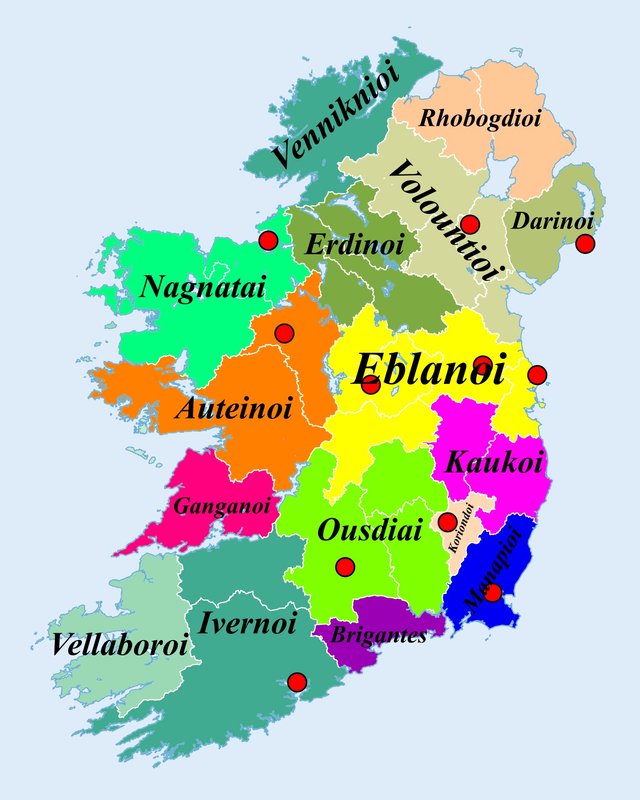

Ptolemy records sixteen tribes in his description of Ireland (the following map should not be taken too seriously):

Three of these can be linked with some degree of confidence with historical tribes of Fir Bolg:

The Volountioi were the ancestors of the Ulaid, who were the dominant people in Ulster (to which they lent their name) in the early centuries of the Common Era.

The Ivernoi were the forerunners of the historical Érainn, who were the dominant people in County Cork prior to the invasion and conquest of Munster by the Goidelic Eóganachta.

The Auteinoi were identical with the Uaithni. These people were found in Counties Limerick and Tipperary in historical times, but tradition has it that they originally dwelt to the west of the Shannon, where Ptolemy places the Auteinoi. O’Rahilly surmises that they may have been of mixed Cruthnian and Bolgic origin, and may even have acquired a Laginian element after Pytheas’s time.

It is probably also safe to regard Ptolemy’s Manapioi and Brigantes as Bolgic tribes (O’Rahilly 33, 34). The identities of the remaining eleven tribes are uncertain, though speculation is rife. None of them, however, can be seriously linked with either Laginian or Goidelic tribes of the historical period.

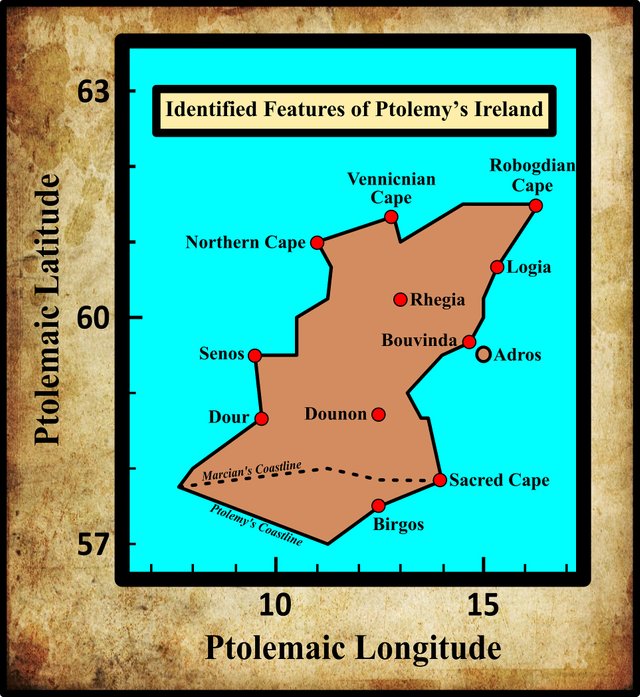

Identified Locations

Notwithstanding endless theorizing on the part of scholars, most of the forty geographical features recorded by Ptolemy in his description of Ireland remain of uncertain identity. A small number of them, however, have been identified with a high degree of certainty—in my opinion, at least. I take my leave of Claudius Ptolemy and his remarkable map of Ireland with a list of these features:

| Greek | Latin | English | Identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Βορειον ακρον | Boreum promontorium | Northern Cape | Bloody Foreland |

| Ουεννικνιον ακρον | Vennicnium promontorium | Vennicnian Cape | Banba’s Crown (Malin Head) |

| ‘Ροβογδιον ακρον | Rhobogdium promontorium | Robogdian Cape | Fair Head |

| Σηνου ποταμου εκβολαι | Seni fluvii ostia | Estuary of the River Senos | Shannon Estuary |

| Δουρ ποταμου εκβολαι | Dur fluvii ostia | Estuary of the River Dour | Lee River (Tralee) |

| Βιργου ποταμου εκβολαι | Birgi fluvii ostia | Estuary of the River Birgos | Waterford Harbour |

| ’Ιερον ακρον | Sacrum promontorium | Sacred Cape | Carnsore Point |

| Βουουινδα ποταμου εκβολαι | Buvindae fluvii ostia | Estuary of the Bovinda | Mouth of the Boyne |

| Λογια ποταμου εκβολαι | Logiæ fluvii ostia | Estuary of the River Logia | Belfast Lough |

| ‘Ρηγια | Regia | Rhegia | Emain Macha |

| Δουνον | Dunum | Dounon | Dinn Righ |

| Ἀδρου ἐρημος | Adru insula deserta | Adrou, uninhabited | Howth Peninsula |

References

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of the Pretannic Isles: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Ptolemy’s Tribes of Ireland: Adapted from File:Ireland trad counties named.svg, after File:Ireland complete.svg, Future Perfect at Sunrise, Public Domain