As we have seen, Claudius Ptolemy records the names and disposition of sixteen Irish tribes in his Geography, Book 2, Chapter 2, §§ 2, 4, 6, and 8. Before we move on to the final section of his description of Ireland, which enumerates the offshore islands, let us step back and survey Ptolemy’s Ireland from an ethnic or political point of view.

The first point to make is that, while Ptolemy’s description of Ireland includes a list of seven “cities” in the interior of the island, his sixteen tribes are all described as inhabiting the coasts:

§ 2 North Coast: Venniknioi, Rhobogdioi

§ 4 West Coast: Venniknioi, Erdinoi, Nagnatai, Auteinoi, Ganganoi, Vellaboroi

§ 6 South Coast: Vellaboroi, Ivernoi, Ousdiai (or Vodiai), Brigantes

§ 8 East Coast: Rhobogdioi, Darinoi, Volountioi, Eblanoi, Kaukoi, Manapioi, Koriondoi, Brigantes

In the previous article, however, we saw that the location of the Ousdiai was somewhat ambiguous. I am still uncertain whether Ptolemy intended to place them to the north of the Ivernoi, making them an inland tribe, or to the east of the Ivernoi, which would put them somewhere on the coast in County Cork or County Waterford. A case could also be made for placing the Koriondoi inland of the Brigantes. But even if we concede these two exceptions, all fourteen of the remaining tribes dwelt on the coast.

So who inhabited the interior of the country? Who occupied those inland “cities”?

The simplest answer is that the territories of at least some of the coastal tribes extended for a considerable distance inland, so that the entire island was covered between the sixteen of them. It is, of course, possible that there were inland tribes of which Ptolemy knew nothing, but as his informant knew of and named several inland settlements, it stands to reason that he would also have known of and named any inland tribes who occupied those settlements.

In historical times, Celtic Ireland was always a patchwork of petty kingdoms. The entire island was traditionally divided into five provinces or fifths (Middle Irish: coiced, fifth): Ulster, Munster, Leinster, Connacht and Meath. The ruler of each of these was a king (MI: Rí), with the ruler of Meath (ie King of Tara) being recognized as the High King of Ireland (Árd-Rí Érenn)—though this was often little more than a legal fiction. Each province, however, was itself subdivided into innumerable smaller territorial divisions. A tuath (plural: tuatha) was the smallest division whose ruler was legally entitled to style himself Rí. The number of tuatha was continually fluctuating, as neighbouring kings were constantly warring with one another, but it was probably never less than several dozen. According to the Irish historian Eoin MacNeill there were about 80 tuatha at a given time (MacNeill 96). A more recent historian almost double’s MacNeill’s estimate:

... there were probably no less than 150 kings in the country at any given date between the fifth and twelfth centuries. (Byrne 7)

When the Anglo-Normans invaded Ireland, they divided the country into territorial divisions known as cantreds. These were the successors of the native trícha cét [30 Hundreds], territories capable of fielding up to 3000 warriors, but these were possibly coterminous with the contemporary tuatha (Dinneen 1254, 1267). Paul MacCotter of University College Cork claims that a recent study of cantreds has demonstrated the existence of 151 certain cantreds and indicated the probable existence of a further 34 (Paul MacCotter 308). Giraldus Cambrensis, a Welsh scholar, who lived at the time of the Norman Invasion, put the number of cantreds at 176 (Gerald of Wales 118).

If Ptolemy’s Geography, however, describes Ireland as it stood around 325 BCE—as T F O’Rahilly has forcefully argued (O’Rahilly 39-42)—then perhaps we ought not be surprised that the country comprised at that time only sixteen significant territorial divisions.

Ptolemy’s description of Ireland includes ten settlements—Greek: πολις [polis], city, citadel (Liddell & Scott 1240)—seven inland and three on the coast. It has been claimed by some scholars that Isamnion was also a town, making eleven in total. As this agrees with the eleven notable towns mentioned by Marcian of Heraclea in the 4th century CE (Marcian 560-561, Miller 104), let us accept it. Some of those scholars would like to identify Isamnion with Emain Macha, or Navan Fort, the ancient “capital” of Ulster in County Armagh, but Ptolemy clearly places Isamnion on the east coast, and that is where I propose to leave it. In an earlier article, I tentatively identified it with St John’s Point in County Down, a promontory.

Let’s assume that none of Ptolemy’s sixteen tribes possessed more than one settlement. Let’s also assume that the boundaries between neighbouring tribes were formed by natural features, such as rivers and mountain ranges. Can we divide the country among the sixteen tribes in a reasonable manner while adhering to these two assumptions?

I cannot. These assumptions are too restrictive.

Below is a hypothetical reconstruction that relaxes both assumptions. It is not to be taken too seriously, however. There are thirty-two traditional counties in Ireland, and while the borders of these counties certainly do not go back to 325 BCE, they are of some considerable antiquity. The River Shannon, for example, provides a natural boundary for ten counties. Sixteen divides into thirty-two twice. Can we perhaps distribute the traditional counties among Ptolemy’s sixteen tribes by allocating two adjacent counties to each tribe?

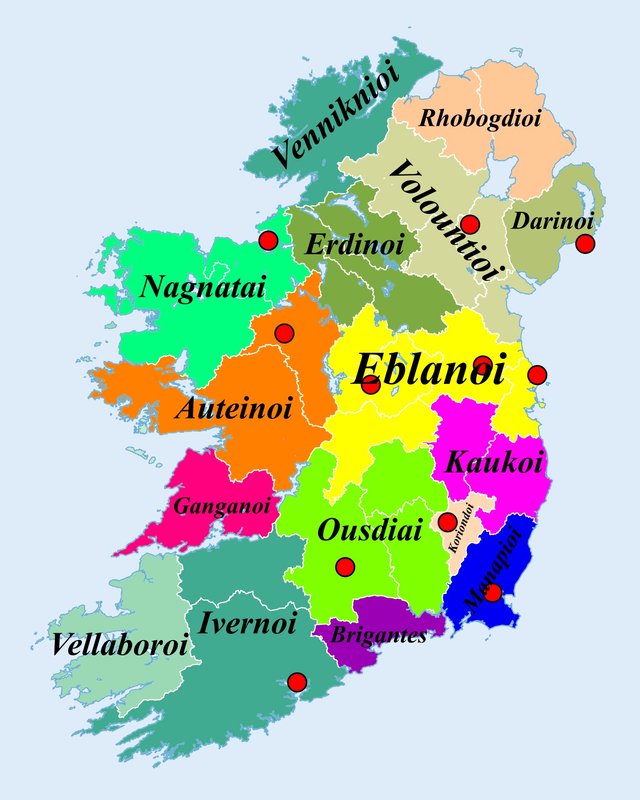

Again, I cannot. Half of the tribes, for example, inhabited the east coast, where there are only seven counties. But by giving some tribes a single county and others three or four, we can at least produce a reasonable political map of Ptolemy’s Ireland, one which might form the basis for further investigation. The settlements (red dots) correspond to the tentative identifications I made in previous articles:

Some Points of Note

Four of Ptolemy’s settlements—Manapia, Eblana, Nagnata and Ivernis—are named for the local tribe. This constrains our division. But is it possible that these towns were unnamed in Ptolemy’s source? If it was Ptolemy himself who gave them these names, then there remains the possibility that he misassigned one or more of them.

With only eleven settlements to choose from, necessarily five or six tribes must be left without any settlements. In fact, it is well-nigh impossible to distribute these settlements among precisely eleven tribes. If we adhere to our tentative identifications of these settlements, then some tribes may end up with two or even three settlements in their territory.

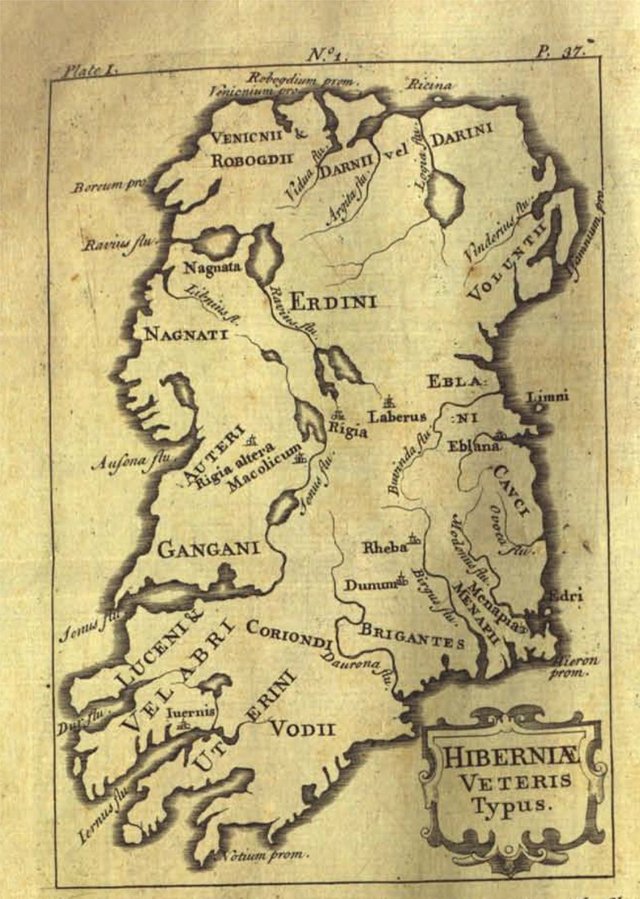

Ptolemy was adamant that the Brigantes were the inhabitants of the southeastern corner of the country. He placed them at the end of both the east and the south coasts. In an earlier article, I placed them in the extreme south of County Wexford, leaving the Koriondoi and Manapioi to dispute the remainder of the county. In the map above, I have assigned County Waterford to the Brigantes, County Carlow to the Koriondoi, and County Wexford to the Manapioi—neat, but hardly realistic. Goddard Orpen, you may recall, suggested a connection between the Brigantes and the Comeragh Mountains, which are in County Waterford. In the 17th century, the Irish antiquary James Ware placed the Brigantes in Counties Carlow, Kilkenny and Laois (Ware & Harris 38), while his editor Walter Harris has them in County Waterford (Ware & Harris 37, Plate 1). The Koriondoi Ware placed in Counties Cork, Tipperary and Limerick:

As I said, this arrangement is not to be taken as a serious attempt to reconstruct the territorial divisions of Ireland 2350 years ago. It is only intended to form a point of departure for further research.

References

- Francis J Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, Four Courts Press, Dublin (1973)

- Patrick S Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla: An Irish-English Dictionary, New and Revised Edition, Irish Texts Society, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1927)

- Seán Duffy, Atlas of Irish History, Third Edition, Gill and MacMillan, Dublin (2011)

- Gerald of Wales, Thomas Forester (translator), Richard Colt Hoare (translator), Thomas Wright (editor), The Historical Works of Giraldus Cambrensis, George Bell & Sons, London (1905)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Paul MacCotter, Functions of the Cantred in Medieval Ireland, Pertitia, Volume 19, p 308, Brepols, Online (2005)

- Eoin MacNeill, Early Irish Laws and Institutions, Burns, Oates and Washbourne, London (1934)

- Emmanuel Miller, _Périple de Marcien d’Héraclée, Epitome d’Artémidore, Isidore de Charax, etc., ou, Supplément aux Dernières Éditions des Petits Géographes : D’après un Manuscrit Grec de la Bibliothèque Royale _, L’Imprimerie Royale, Paris (1839)

- Marcian, Karl Müller (editor), Geographi Græci Minores, Volume 1, Firmin-Didot, Paris (1882)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of the Pretannic Isles: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Ptolemy’s Ireland (Duffy): © Seán Duffy 2000, Fair Use

- Ptolemy’s Tribes of Ireland: Adapted from File:Ireland trad counties named.svg, after File:Ireland complete.svg, Future Perfect at Sunrise, Public Domain