What is so special about Mr. Gunther Schuller? How did jazz music become such a high art form after its renown as “pop music?” The high esteem of swing music in the 1930s and 1940s, followed by the revolution that was bebop made jazz music hard to ignore. Around the same time period, composers such as Arthur Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Igor Stravinsky were making new milestones in classical music with their continuous will to innovate away from Romantic music in concert halls in the United States and Europe. In the 1950s, both jazz and modernist classical music had made a large mark on music in general. Composers and arrangers in both realms wanted to further innovate and go their own ways.

Gunther Schuller was born in New York in 1925. He started his musical career as the principle French horn player for the Cincinnati Symphony in ballets. He was also very interested in jazz, playing in Miles Davis and Gil Evans’ Birth of the Cool sessions from 1949-1950 (New England Conservatory Archives). From then on, he became an esteemed composer and music educator; teaching at the Manhattan School of Music from 1950-53, becoming professor of composition at Yale University, and helping to establish the first jazz degree program in 1969 during his tenure at the New England Conservatory (New England Conservatory). His compositions were very diverse, ranging from solo, orchestral, chamber, opera, and jazz works. At a lecture at Brandeis University in 1957, Schuller coined the term “Third Stream” as a style of music between classical and jazz (Ibid). In 1959, he composed one of his most famous Third Stream works 7 Studies on the Themes of Paul Klee, based on 7 works of art by the Swiss artist Paul Klee.

Although the music of 7 Studies is attributed to Schuller, it would be greatly misleading to only attribute this piece to his ingenuity. Paul Klee was a musician-turned-artist born in the late 19th century in Switzerland. Growing up playing violin, he decided to pursue visual art instead by the age of 19. His artwork was said to belong to the cubist, expressionist, and surrealist traditions (biography.com). He had his first solo exhibition in Bern in 1910, followed by similar shows in three other Swiss cities (biography.com). By 1917, he had moved to Germany and became one of the most critically acclaimed German artists (Ibid). He taught at the Bauhaus and Dusseldorf academies in the 1920s to the early 1930s, when he was fired from Dusseldorf by the Nazis, having deemed his art to be inappropriate. Gunther Schuller’s 7 Studies on the Themes of Paul Klee further pushed the boundaries of music as an art form by combining modernist experiments in 20th century classical music and jazz through musical emulation of seven of Klee’s paintings.

It is important to note that the piece is not just a musical interpretation of the particular artwork in question. In the preface to the score, Schuller indicates “Each of the seven pieces bears a slightly different relationship to the original Klee picture from which it stems. Some relate to the actual design, shape or color of the painting, while others take the general mood of the picture or its title as a point of departure” (Schuller: 7 Studies on the Themes of Paul Klee Score 1959). Klee himself reflected music in his artwork, “fascinated in his painting by the possibilities of “variation” or “fugal” techniques and rhythm and polyphony as applied to pictoral design” (Schuller).

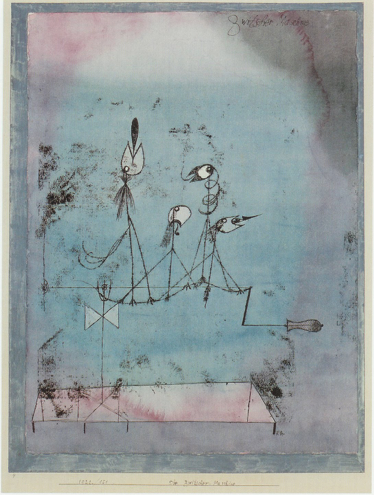

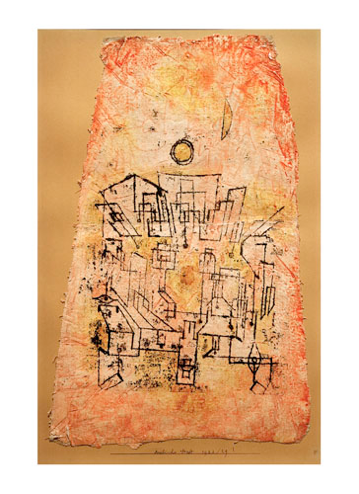

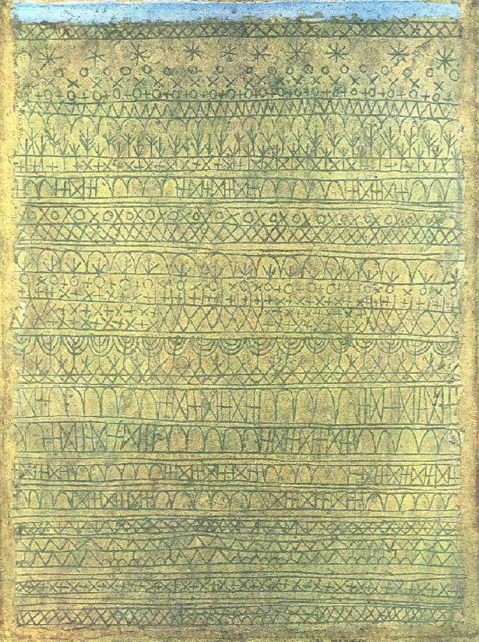

The piece opens with “Antique Harmonies” (see Appendix 1). The respective painting shows Klee’s “cubist” tendency because it is a series of differently colored squares, which are darker on the edges and brighter near the center. Schuller musically emulated the brown colors through quiet, minor-sounding harmonization, which form the background of the movement. Over the background lie “blocks of lighter colored fifths gradually pile up, reaching a climax in the brighter yellow of the trumpets and the high strings” (Ibid). The following movements follow suit in emphasizing various elements of the different paintings. The second movement, “The Abstract Trio,” emulates the painting of three obscure shapes by playing the piece “almost entirely by three instruments at any given time” (Ibid) (see Appendix 2). “Little Blue Devil” is made to sound whimsical with the short statements that bring out Klee’s geometric shapes (see Appendix 3). The color blue is signified through the usage of a blues form. “The Twittering Machine,” turns the odd-looking device with bird heads in the painting into instruments that sound like they “twitter” frantically (see Appendix 4). It looks like there is a wooden crank in the painting that activates the machine when wound, which is most likely represented by the stuttering sound of the strings in music, followed by the high-pitched sounds from woodwinds. The fifth movement, “Arab Village,” makes the listener imagine what the place the title implies might look like with the usage of many middle-eastern scales (see Appendix 5). “An Eerie Moment,” takes inspiration from a somewhat rare painting of Klee’s. The actual painting has a clear, white background with several ink scribbles (see Appendix 6). Schuller said that the movement “is a musical play more on the title than on Klee’s actual pen drawing” (Schuller). The finale, “Pastorale” emulates the artwork by keeping the rhythmic pattern in the strings very constant while sometimes randomly changing the melodic structure and textures in the winds (see Appendix 7).

One must not forget the extremely modernist and sometimes even avant-garde elements of the entire piece. Five of the movements: “Abstract Trio” (2), “Little Blue Devil” (3), “Twittering Machine” (4), “An Eerie Moment” (6), and “Pastorale” (7) use tone rows in certain ways, much like serialist composers such as Schoenberg and Webern. Similar to Olivier Messiaen, “The Twittering Machine” emulates bird sounds through the high woodwinds. The entrance of lower woodwinds signifies the “winding down” of the machine (Schuller: 7 Studies on the Themes of Paul Klee Recording). Schuller also riddles a few of the movements with serialization of other elements besides tones. In “The Abstract Trio,” there are only three instruments playing at a time, having a pattern of flute, oboe, and clarinet, then bassoon and muted brass (trumpet and trombone), followed by low brass and bass clarinet. Beginning with the winds, the instruments trade off in playing statements ordered as oboe, clarinet, flute, clarinet, flute, oboe, flute, clarinet, and oboe (Schuller recording). There are also several movements that utilize more tonal elements, but are still pretty modernistic. In “Antique Harmonies,” open fifths are used by winds in contrast with the string backgrounds. This interval was not very common in romantic music, so this technique is seen as very innovative for the time. This repeated cadence could also be seen as making the movement neo-classical, drawing rough influence from older music as well as establishing a neo-tonality. Schuller even states that this established the antique quality (Ibid). “Pastorale” also uses a repeated cadence establishing a neo-tonality much like “Antique Harmonies.” The fifth movement, “Arab Village,” uses scales played by the flute and a slightly out-of-tune unison between an oboe and a pizzicato solo string instrument. “Little Blue Devil” is a stark example of Schuller’s Third Stream style; utilizing an entire percussion section to play a swung rhythm pattern, brief statements by a walking bass line, and a 9-bar blues form (Schuller Score).

It is with this piece that Gunther Schuller cements himself as a modern artist and composer by envisioning what modern, 20th century visual art might sound like in an even more modern context. Paul Klee’s visual artwork that is heavily inspired by music comes full circle through Schuller’s vision of it as musical sound through his own artistic influences. This ultimate fusion of different forms of art made its mark on 20th century modernist and avant-garde music.

You can hear a recording of this piece in all 7 movements here:

Appendix of Artwork

Appendix 1: Antike Harmonien (Antique Harmonies)- Paul Klee

Appendix 2: Abstraktes Trio (Abstract Trio)- Klee

Appendix 3: Kleiner Blauer Teufel (Little Blue Devil)- Klee

Appendix 4: Die Zwitschermaschine (The Twittering Machine)

Appendix 5: Arabische Stadt (Arab Village)

Appendix 6: Ein unheimlicher Moment (An Eerie Moment)

Appendix 7: Pastorale

Bibliography

Bio. “Paul Klee Biography.”

< http://www.biography.com/people/paul-klee-9366304>

(Accessed 27 May 2015).

Klee, Paul. Abstraktes Trio. 1923. Watercolor from pencil drawing, 12.5 x 19.75 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. From: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

< http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1984.315.36>

(Accessed 23 May 2015).

Klee, Paul. Antike Harmonien. c. 1925. Digital Image.

Available from: Classical Music Brain Droppings.

< https://sites.google.com/a/colgate.edu/colgatevr/citing-images/citing-images-chicago> (Accessed 23 May 2015).

Klee, Paul. Arabische Stadt. Digital Image. Available from: ArtRepublic

< http://www.artrepublic.com/prints/16616-arab-city.html>

(Accessed 23 May 2015).

Klee, Paul. Die Zwitschermaschine. Digital Image.

Available from: Classical Music Brain Droppings.

< https://sites.google.com/a/colgate.edu/colgatevr/citing-images/citing-images-chicago> (Accessed 23 May 2015).

Klee, Paul. Ein Unheimlicher Moment. 1912. Digital Image.

Available from: Art into Music.

< http://www.indiana.edu/~dws/art_music/pages/06Klee.EerieMom.htm>

(Accessed 23 May 2015).

Klee, Paul. Kleiner Blauer Teufel. 1933. Digital Image.

Available from: Classical Music Brain Droppings.

< http://www.artrepublic.com/prints/16616-arab-city.html>

(Accessed 23 May 2015).

Klee, Paul. Pastorale. 1927. Digital Image.

Available from: Classical Music Brain Droppings

< http://www.artrepublic.com/prints/16616-arab-city.html>

(Accessed 23 May 2015).

New England Conservatory. “Gunther Schuller.”

< http://necmusic.edu/archives/gunther-schuller>.

(Accessed 27 May 2015)

Schuller, Gunther. Seven Studies on the Themes of Paul Klee.

Universal Edition, 1959.