Unexamined belief in the validity of that assertion has now resulted in the balagan at the border. If all men (and women) are equal, then aren’t we all equally entitled to choose where we wish to live? And if tens of millions or hundreds of millions of people from around the world choose to live in the USA, who are we to say them nay?

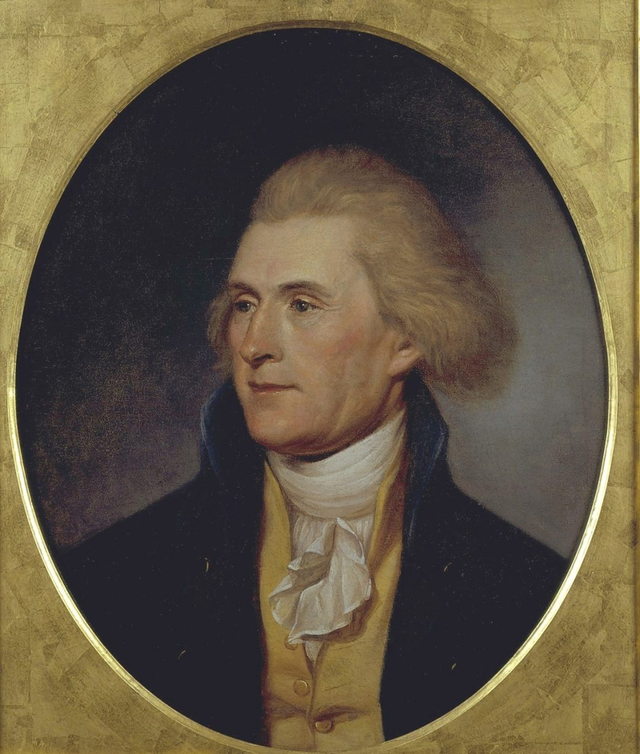

Thomas Jefferson’s statement about human equality can be viewed as offering support for open borders. So can the words of Emma Lazarus:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.”

Who will argue with the author of the Declaration of Independence or with the author of “The Colossus,” a poem cast on a bronze plaque and mounted on the base of the Statue of Liberty? Americans so revere Jefferson and Lazarus that we can easily lose sight of how their words have been interpreted – or misinterpreted – in the great national debate over the desirable qualifications, size, and scope of immigration.

I'm currently reading several books about Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence, trying to more fully understand Jefferson's intent in writing it, as well as the consequences -- intentional or otherwise -- of the specific language he employed. If my suggestion (above) that Jefferson's claim that "all men are created equal" forms the basis for one strongly-held (and predominantly liberal) point of view about immigration, then it may still be useful to closely examine the particular words he used. And since most Americans, even those who know the Declaration of Independence well, may have little or no familiarity with the works of Locke or Montesquieu or Algernon Sidney, any attempt to fully grasp the meaning of America's founding document should start with the text itself.