James K Hoffmeier is a Biblical scholar and archaeologist with a special interest in the historicity of the Old Testament. Born in Egypt in 1951, he is currently Professor Emeritus of Old Testament and Near Eastern Archaeology at Trinity International University, Divinity School, in Deerfield, Illinois.

In this article, we will examine Hoffmeier’s opinions on the historicity of the Biblical leader Joshua and of his Conquest of Canaan as it is related in the Book of Joshua. In the ongoing scholarly debate on this subject, Hoffmeier has unashamedly championed the authenticity of the Biblical account:

The nature of Israel’s origins has been the subject of considerable scholarly discussion over the past two decades. Although there are a number of different theories about who early Israel was and where they came from, the theories fall into three groups: first, those that believe that Israel entered Canaan from the outside (either as invaders or peacefully infiltrating emigrants); second, those that maintain that Israel was an indigenous development within Canaan; and third, those that advocate some sort of combination of the two.

The material present in this study tends to support the first model, while casting serious doubt on the indigenous development theory. (Hoffmeier 2005:235)

Joshua’s Conquest Narratives

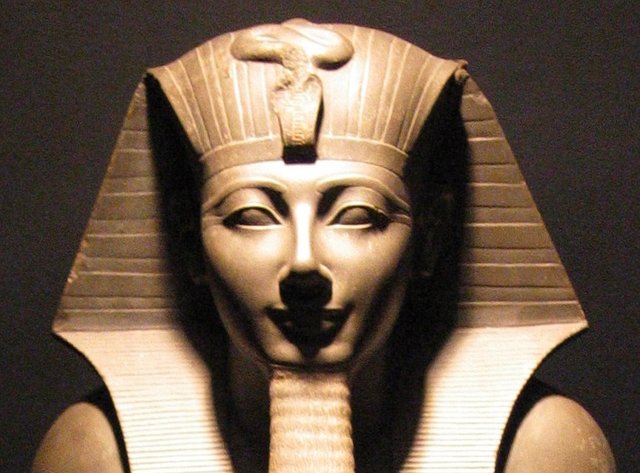

In a paper published in 1994, when he was Professor of Archaeology and Old Testament at Wheaton College in Illinois, Hoffmeier compares the conquest narratives recorded in the first eleven chapters of the Book of Joshua to the campaign annals of Thutmose III of the 18th Dynasty.

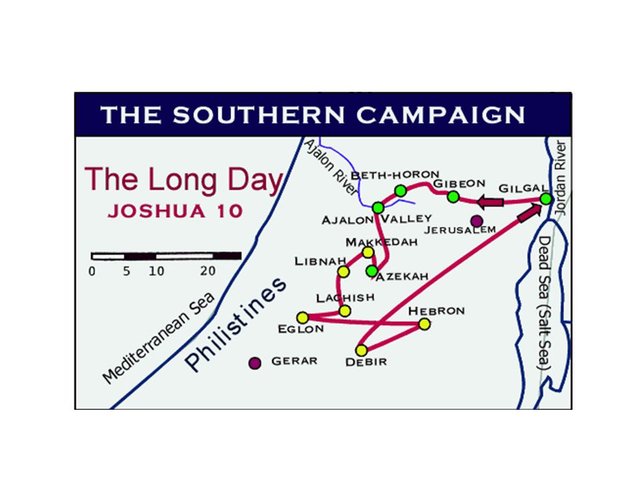

Hoffmeier begins his analysis with Joshua 10:28-42, which describes Israel’s attacks on six cities in southern Canaan—Makkedah, Libnah, Lachish, Eglon, Hebron and Debir—during Joshua’s second campaign. In each case, the city was taken, its king and inhabitants were put to the sword, but the city was not occupied by the Israelites:

And that day Joshua took Makkedah, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and the king thereof he utterly destroyed, them, and all the souls that were therein; he let none remain: and he did to the king of Makkedah as he did unto the king of Jericho. Then Joshua passed from Makkedah, and all Israel with him, unto Libnah, and fought against Libnah: And the Lord delivered it also, and the king thereof, into the hand of Israel; and he smote it with the edge of the sword, and all the souls that were therein; he let none remain in it; but did unto the king thereof as he did unto the king of Jericho. And Joshua passed from Libnah, and all Israel with him, unto Lachish, and encamped against it, and fought against it: And the Lord delivered Lachish into the hand of Israel, which took it on the second day, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and all the souls that were therein, according to all that he had done to Libnah. Then Horam king of Gezer came up to help Lachish; and Joshua smote him and his people, until he had left him none remaining. And from Lachish Joshua passed unto Eglon, and all Israel with him; and they encamped against it, and fought against it: And they took it on that day, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and all the souls that were therein he utterly destroyed that day, according to all that he had done to Lachish. And Joshua went up from Eglon, and all Israel with him, unto Hebron; and they fought against it: And they took it, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and the king thereof, and all the cities thereof, and all the souls that were therein; he left none remaining, according to all that he had done to Eglon; but destroyed it utterly, and all the souls that were therein. And Joshua returned, and all Israel with him, to Debir; and fought against it: And he took it, and the king thereof, and all the cities thereof; and they smote them with the edge of the sword, and utterly destroyed all the souls that were therein; he left none remaining: as he had done to Hebron, so he did to Debir, and to the king thereof; as he had done also to Libnah, and to her king. So Joshua smote all the country of the hills, and of the south, and of the vale, and of the springs, and all their kings: he left none remaining, but utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the Lord God of Israel commanded. And Joshua smote them from Kadeshbarnea even unto Gaza, and all the country of Goshen, even unto Gibeon. And all these kings and their land did Joshua take at one time, because the Lord God of Israel fought for Israel. (Joshua 10:28-42)

Hoffmeier notes how earlier scholars have already recognized that this passage is quite different from any which precede it in the Book of Joshua (Hoffmeier 1994:167). Taken together, the descriptions of these six engagement are constructed from a set of eleven basic elements or syntagms:

Joshua’s departure from the conquered city.

All Israel accompanies him.

Joshua’s arrival at the next city.

A brief description of the military engagement.

YHWH delivers the city and its king into the hands of Israel.

An attempt is made to date the campaign or to give its duration.

The city, its king and its inhabitants are put to the sword.

The extent of the destruction of the population is described.

The present destruction is compared with another victory.

An additional note is given concerning the campaign.

The taking of booty is mentioned.

Each engagement is described using at least five and as many as ten of these syntagms. In chapter 11, the account of the capture and destruction of Hazor in northern Canaan is similarly constructed from seven of the same syntagms:

And Joshua at that time turned back, and took Hazor, and smote the king thereof with the sword: for Hazor beforetime was the head of all those kingdoms. And they smote all the souls that were therein with the edge of the sword, utterly destroying them: there was not any left to breathe: and he burnt Hazor with fire. And all the cities of those kings, and all the kings of them, did Joshua take, and smote them with the edge of the sword, and he utterly destroyed them, as Moses the servant of the Lord commanded. But as for the cities that stood still in their strength, Israel burned none of them, save Hazor only; that did Joshua burn. And all the spoil of these cities, and the cattle, the children of Israel took for a prey unto themselves; but every man they smote with the edge of the sword, until they had destroyed them, neither left they any to breathe. (Joshua 11:10-14)

Having analysed these passages, Hoffmeier now proceeds to show that an Egyptian scribal tradition may well have influenced their composition (Hoffmeier 1994:169). He notes particularly the similar structure of many of the Annals of Thutmose III with the exception of those concerning his first campaign:

... a special document lay behind the first campaign because of its importance, and the primary source behind the remainder of the Annals was the Daybook [hrwyt] of the King’s Palace. (Hoffmeier 1994:171).

That records of military campaigns were compiled in the field in a Daybook by eye-witnesses is confirmed by one such witness, the military scribe Tjaneny, who records:

I saw the victories of the king which he made over every foreign land ... It was I who recorded the victories which he achieved over all foreign lands, it being put into writing according to what was done. (Hoffmeier 1994:172)

Hoffmeier also suggests that Thutmose’s first campaign, which is described in much greater detail than the majority of his subsequent campaigns, bears comparison with the Biblical description of Joshua’s first campaign—the siege and capture of Jericho (Joshua 1-6). He notes six major components common to both reports:

Some might argue that these similarities are superficial and demonstrate no literary relationship between the two, and that may be the case. But the structural similarity cannot be dismissed out of hand. Minimally, the similarities illustrate that the Joshua narrative is no orphan when compared to a piece of Egyptian military writing and that whatever ideological concerns may have shaped the Joshua narratives, they remain comparable to their counterparts elsewhere in the second-millennium Near East. (Hoffmeier 1994:173)

In the Short Chronology, Joshua’s Conquest of Canaan occurred near the start of the 18th Dynasty, about a century before the reign of Thutmose III. But Hoffmeier is not claiming that Thutmose’s Annals provided a direct model for Joshua’s campaign narratives, merely that the latter were influenced by an Egyptian scribal tradition that was already in place before the Exodus:

Drawing a comparison with Thutmose III’s annals does not necessarily give a date for the Joshua narratives, since elements of this genre are found in Egypt in the Ramesside era, as well as in the military documents of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty. However, the late period, it must be recalled was one of literary and artistic renaissance, and thus the occurrences of the annals genre in the eighth and seventh centuries in Egypt likely represent archaisms. (Hoffmeier 1994:176-177)

It is common for archaeologists to invoke archaisms and renascences to account for such anomalies as these strong similarities between the 19th Dynasty (Ramesside) and the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (Nubian). In the conventional Egyptian chronology, these two dynasties were separated by 450 years. In the Short Chronology, however, they actually overlapped, so there is no anomaly (Sweeney 15).

The Ceremony at Mount Ebal

Joshua’s first campaign is described in Chapters 5-8 of the Book of Joshua. It leads to the capture and destruction of two Canaanite cities, Jericho and Ai. Following this campaign, the Israelites conduct a ceremony on Mount Ebal, which lies about 34 km north of Ai, in the territory later allotted to Manasseh:

Then Joshua built an altar unto the Lord God of Israel in mount Ebal, As Moses the servant of the Lord commanded the children of Israel, as it is written in the book of the law of Moses, an altar of whole stones, over which no man hath lift up any iron: and they offered thereon burnt offerings unto the Lord, and sacrificed peace offerings. And he wrote there upon the stones a copy of the law of Moses, which he wrote in the presence of the children of Israel. And all Israel, and their elders, and officers, and their judges, stood on this side the ark and on that side before the priests the Levites, which bare the ark of the covenant of the Lord, as well the stranger, as he that was born among them; half of them over against mount Gerizim, and half of them over against mount Ebal; as Moses the servant of the Lord had commanded before, that they should bless the people of Israel. And afterward he read all the words of the law, the blessings and cursings, according to all that is written in the book of the law. There was not a word of all that Moses commanded, which Joshua read not before all the congregation of Israel, with the women, and the little ones, and the strangers that were conversant among them. (Joshua 8:30-35)

Hoffmeier believes that this ceremony was concerned with the legal granting of the conquered land to Israel:

After the campaign against Ai, the Israelites undertook a ceremony at Mt. Ebal (Josh. 8:30-35). Andrew Hill has, in my opinion, rightly identified this as a divine land grant ceremony, like the royal deeds of Mesopotamia. Just as kudurru-stones were used in Babylon in connection with land grants, Moses directed the erection of a stone on which the words of the covenant-land grant deed were to be written: “When you pass over to enter the land which the Lord your God gives you ...” (Deut. 27:2-8). (Hoffmeier 1994:174)

This was also common practice among the Egyptian Pharaohs:

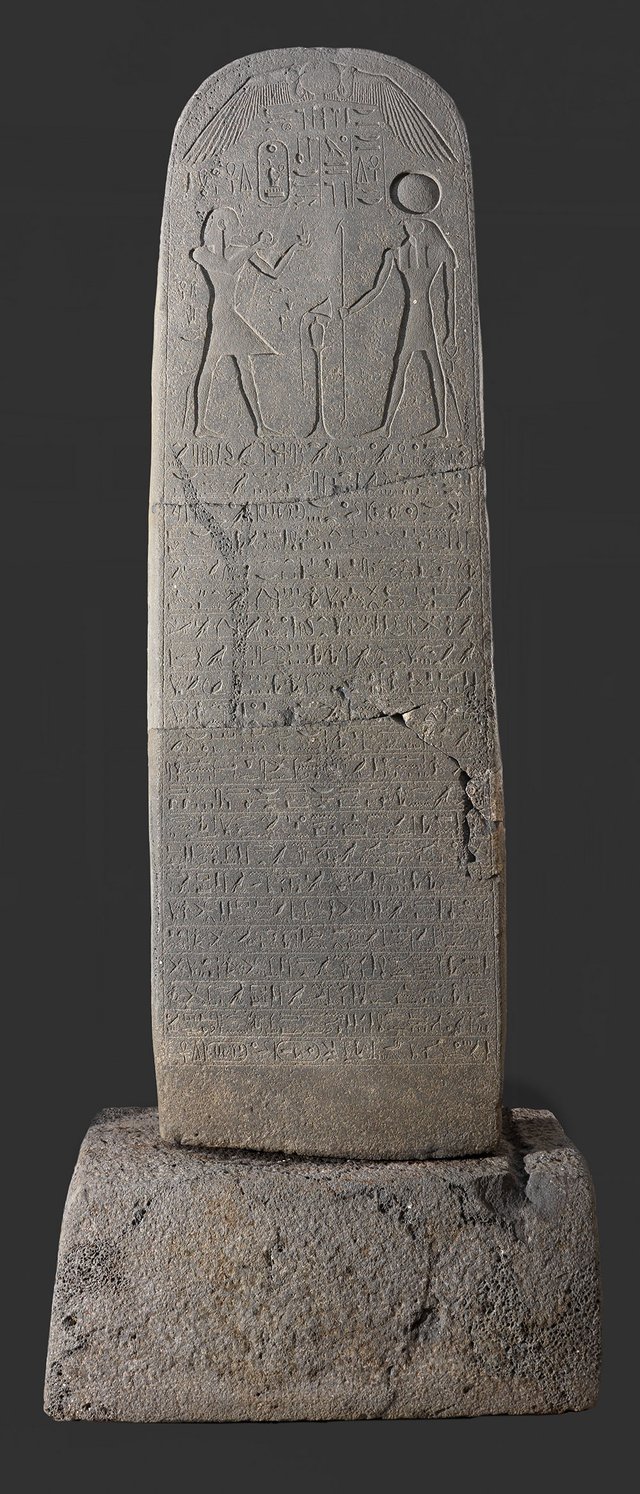

Thutmose III records that he erected a stela beside that of his grandfather, Thutmose I, on the east side of the Euphrates. He also set up two stelae on the west side of the Euphrates and one at Niy. A number of Nineteenth-Dynasty stelae have been discovered in Palestine and Phoenicia ... Thus, it appears that the practice of erecting an inscribed stone as a claim of ownership in connection with a military campaign as reported in Josh. 8:32 finds many parallels in the Middle and New Kingdom periods. (Hoffmeier 1994:175)

Summary

The successful conclusion of Joshua’s southern campaign is summarized in a few verses near the end of Chapter 10:

So Joshua smote all the country of the hills, and of the south, and of the vale, and of the springs, and all their kings: he left none remaining, but utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the Lord God of Israel commanded. And Joshua smote them from Kadeshbarnea even unto Gaza, and all the country of Goshen, even unto Gibeon. And all these kings and their land did Joshua take at one time, because the Lord God of Israel fought for Israel. (Joshua 10:40-42)

This too is typical of contemporary documents:

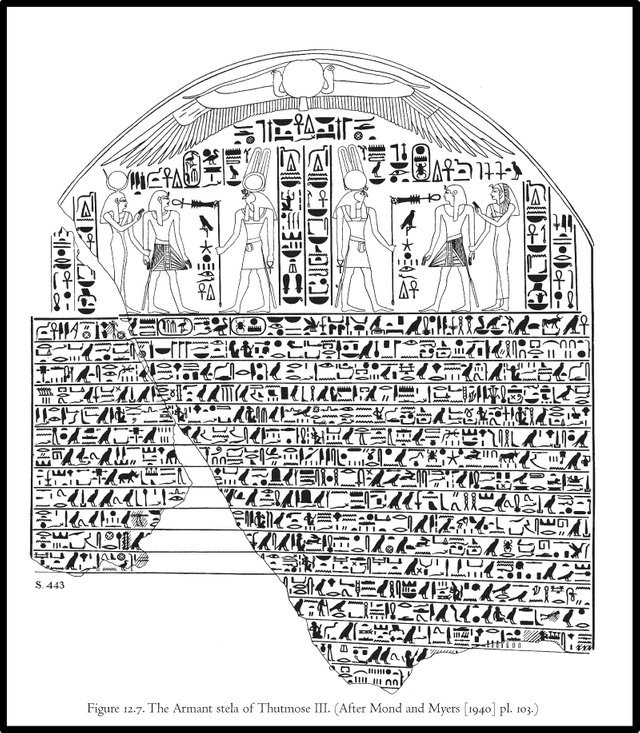

Another feature found in Joshua 10 is the summary (10:40-42) of preceding events (10:28-39), which Younger documents as a literary device found in Assyrian and Egyptian sources, such as in Ramesses II’s Kadesh inscription and Thutmose III’s Armant stela. (Hoffmeier 1994:175)

Hoffmeier concludes his paper with the following remarks:

Based on the Egyptian evidence presented here, the New Kingdom period, when Israel would most likely have departed from Egypt and entered Canaan, proves to be the most likely time for the Egyptian daybook scribal tradition to have been embraced by Israelite scribes and thus to leave its mark on the composition of Joshua. (Hoffmeier 1994:179)

Like Kenneth Kitchen, Hoffmeier makes a strong case for the historicity of Joshua’s Conquest of Canaan. His placement of the Conquest in the New Kingdom period accords with the Short Chronology—though he favours the 19th Dynasty, while I favour the beginning of the 18th Dynasty, just after the interface between the Second Intermediate Period and the New Kingdom.

And that’s a good place to stop.

To be continued ...

References

- James Hoffmeier, The Structure of Joshua 1-11 and the Annals of Thutmose III, in A R Millard, James K Hoffmeier, David W Baker (editors), Faith, Tradition, and History: Old Testament Historiography in Its Near Eastern Context, Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, Indiana (1994)

- James K Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2003)

- Emmet John Sweeney, The Ramessides, Medes and Persians, Ages in Alignment, Volume 4, Algora Publishing, New York (2007)

Image Credits

- James K Hoffmeier: © Huntington University 2020, Fair Use

- Lachish (City Gate): Tel Lakhish, Israel, © Wilson44691, Creative Commons License

- Joshua’s Southern Campaign: © Magdalen Griffith, Fair Use

- Tel Hatzor (Hazor): אסף.צ (photographer), Public Domain

- Thutmose III (Luxor Museum): Luxor Museum, Public Domain

- Mount Gerizim (Left) and Mount Ebal: © Rami Yudovin, Fair Use

- Victory Stela of Seti I (Tel Beth Shean): © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1995-2020, Fair Use

- Armant Stela: © Robert Ludwig Mond & Oliver Humphrys Myers, Temples of Armant: A Preliminary Survey, The Plates, Expedition Memoir 43, Plate 103, Egypt Exploration Society, London (1940), Fair Use