In Joshua 10, one of the most celebrated stories in the Old Testament is recounted:

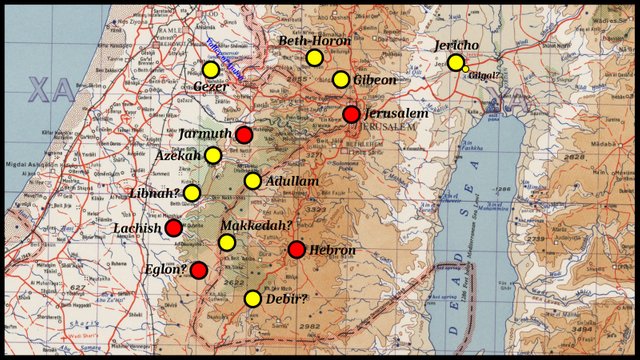

Now it came to pass, when Adonizedec king of Jerusalem had heard how Joshua had taken Ai, and had utterly destroyed it; as he had done to Jericho and her king, so he had done to Ai and her king; and how the inhabitants of Gibeon had made peace with Israel, and were among them; That they feared greatly, because Gibeon was a great city, as one of the royal cities, and because it was greater than Ai, and all the men thereof were mighty. Wherefore Adonizedec king of Jerusalem, sent unto Hoham king of Hebron, and unto Piram king of Jarmuth, and unto Japhia king of Lachish, and unto Debir king of Eglon, saying, Come up unto me, and help me, that we may smite Gibeon: for it hath made peace with Joshua and with the children of Israel.

Therefore the five kings of the Amorites, the king of Jerusalem, the king of Hebron, the king of Jarmuth, the king of Lachish, the king of Eglon, gathered themselves together, and went up, they and all their hosts, and encamped before Gibeon, and made war against it.

And the men of Gibeon sent unto Joshua to the camp to Gilgal, saying, Slack not thy hand from thy servants; come up to us quickly, and save us, and help us: for all the kings of the Amorites that dwell in the mountains are gathered together against us. So Joshua ascended from Gilgal, he, and all the people of war with him, and all the mighty men of valour. And the Lord said unto Joshua, Fear them not: for I have delivered them into thine hand; there shall not a man of them stand before thee. Joshua therefore came unto them suddenly, and went up from Gilgal all night.

And the Lord discomfited them before Israel, and slew them with a great slaughter at Gibeon, and chased them along the way that goeth up to Bethhoron, and smote them to Azekah, and unto Makkedah. And it came to pass, as they fled from before Israel, and were in the going down to Bethhoron, that the Lord cast down great stones from heaven upon them unto Azekah, and they died: they were more which died with hailstones than they whom the children of Israel slew with the sword. Then spake Joshua to the Lord in the day when the Lord delivered up the Amorites before the children of Israel, and he said in the sight of Israel, Sun, stand thou still upon Gibeon; and thou, Moon, in the valley of Ajalon.

And the sun stood still, and the moon stayed, until the people had avenged themselves upon their enemies. Is not this written in the book of Jasher? So the sun stood still in the midst of heaven, and hasted not to go down about a whole day. And there was no day like that before it or after it, that the Lord hearkened unto the voice of a man: for the Lord fought for Israel.

And Joshua returned, and all Israel with him, unto the camp to Gilgal. But these five kings fled, and hid themselves in a cave at Makkedah. And it was told Joshua, saying, The five kings are found hid in a cave at Makkedah. And Joshua said, Roll great stones upon the mouth of the cave, and set men by it for to keep them: And stay ye not, but pursue after your enemies, and smite the hindmost of them; suffer them not to enter into their cities: for the Lord your God hath delivered them into your hand.

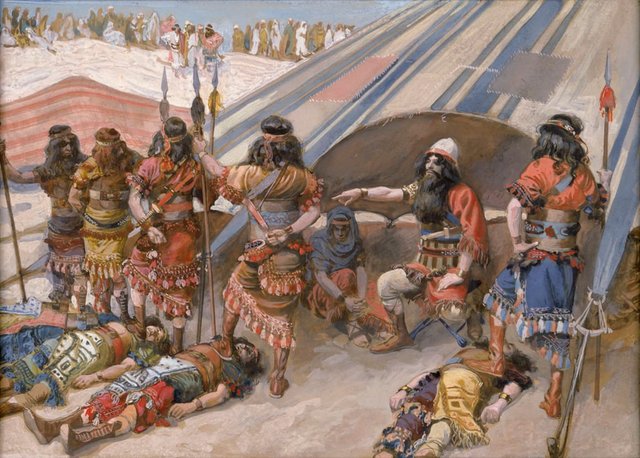

And it came to pass, when Joshua and the children of Israel had made an end of slaying them with a very great slaughter, till they were consumed, that the rest which remained of them entered into fenced cities. And all the people returned to the camp to Joshua at Makkedah in peace: none moved his tongue against any of the children of Israel. Then said Joshua, Open the mouth of the cave, and bring out those five kings unto me out of the cave. And they did so, and brought forth those five kings unto him out of the cave, the king of Jerusalem, the king of Hebron, the king of Jarmuth, the king of Lachish, and the king of Eglon. And it came to pass, when they brought out those kings unto Joshua, that Joshua called for all the men of Israel, and said unto the captains of the men of war which went with him, Come near, put your feet upon the necks of these kings. And they came near, and put their feet upon the necks of them.

And Joshua said unto them, Fear not, nor be dismayed, be strong and of good courage: for thus shall the Lord do to all your enemies against whom ye fight. And afterward Joshua smote them, and slew them, and hanged them on five trees: and they were hanging upon the trees until the evening. And it came to pass at the time of the going down of the sun, that Joshua commanded, and they took them down off the trees, and cast them into the cave wherein they had been hid, and laid great stones in the cave's mouth, which remain until this very day. (Joshua 10:1-27)

The subsequent events recounted in Joshua 10:28-43 will be investigated in future articles in this series.

Unlike the majority of the Bible’s records of Joshua’s campaigns, this story is supported by numerous details. We are not only told the names of the five cities that form an alliance against Gibeon but also the names of their kings:

Adonizedec King of Jerusalem

Hoham King of Hebron

Piram King of Jarmuth

Japhia King of Lachish

Debir King of Eglon

A story is recounted in Judges 1, which features a Canaanite king called Adoni-Bezek. Although he is associated with Bezek—a city of unknown location—he dies in Jerusalem. Some scholars believe that he is the same individual as Adonizedek of Joshua 10, although Judges 1 is set after Joshua’s death:

ADONI-BEZEK—Biblical Data: Canaanitish king (Judges, i. 5-7), in the town of Bezek. He was routed by Judah and fled, but was caught. His thumbs and great toes were cut off, as a divine retribution—as he himself acknowledged—for the same mutilation visited by him upon seventy kings. Such treatment rendered the captives practically harmless in case of war, as they could neither run nor handle the bow. See Adoni-zedek ...

ADONI-ZEDEK (“Zedek is Lord”): King of Jerusalem at the time of the Hebrew invasion of Palestine (Josh. x. 1, 3). He led a coalition of five of the neighboring Amorite cities to resist the invasion, but the allies were defeated at Gibeon, and suffered at Beth-horon, not only from their pursuers, but also from a great hail-storm. The five allied kings took refuge in a cave at Makkedah and were imprisoned there until after the battle, when Joshua commanded that they be brought before him; whereupon they were brought out, humiliated, and put to death. The name Adoni-zedek seems to be corrupted into Adoni-bezek in Judges, i. 5-7. (Singer 204-205)

Adonizedek’s four allies are not known from any other source.

In Joshua 10, the King of Eglon is called Debir. But Debir was also the name of a city, and Eglon was also the name of a Moabite king. In fact, the place Eglon is not mentioned anywhere else in the Bible, and the personal name Debir only occurs in Joshua 10:3. This curiosity has led some scholars to suspect that the source for Joshua 10:3 was corrupt and the phrase ought to read Eglon King of Debir:

The name ‛Debir king of Eglon’ (Joshua 10.3) appears very odd, since Debir is a familiar city name and Eglon prominent as a king’s personal name. Moreover, the LXX has the city name Adullam where MT has Eglon. Various explanations are reviewed. It seems likely that Debir was indeed the city name and that it was transformed into a personal name in the course of redactional processes. (Barr 68)

Barr concurs with the Biblical scholar Martin Noth, who hypothesized that Joshua 10 is a confused conflation of two different stories:

A careful and powerful analysis of the story is found in North’s commentary (1938), pp. 34-41. According to him, there are two major sections which arise from different traditions, later combined. To take the second of these first, the tradition is a local aetiology of Makkedah and its cave, where after their defeat five kings had been closed in and starved to death, or, as others put it, they had been hanged on five trees, still to be seen there, and later put into the cave. The five kings, according to the local tradition, were those of Libnah, Lachish, Eglon, Hebron and Debir, the Canaanite cities that might have prevented Israelite settlement in that territory.

The other tradition is of the same sort as many stories of the Judges, and is based on a setting much further north. The Gibeonites, menaced by the ‛kings of the Amorites’, appealed for help under their covenant with Israel, Joshua, then at Gilgal, marched to Gibeon, was victorious in battle, and pursued the fleeing enemy down the Beth-Horon pass and even as far as Azekah and Makkedah (this last portion of the pursuit may well be the means to link the story of the battle with the other tradition centred in Makkedah). It is not certain that the Israelite leader in the earliest stage of the tradition was Joshua. And this side of the whole tradition must have concerned tribes such as Benjamites or Ephraimites who were in touch with Gibeon, well to the north. If the ‛kings of the Amorites’ were ever more precisely known or defined, they were probably from the area west of Gibeon, to judge by the direction in which their armies fled after the defeat. (Barr 62)

According to Noth’s analysis, when these two traditions were conflated, the five kings executed in the Makkedah tradition were identified with the ‛kings of the Amorites’ of the Gibeon tradition. This still leaves some matters to be accounted for:

What was the source for the names of the five kings?

How was Adonizedek of Jerusalem brought into the story?

Why was Libnah replaced by Jerusalem?

Barr surmises that there were originally more than five cities involved in the story: Libnah, Lachish, Eglon, Hebron, Debir, Jarmuth, Adullam, and possibly also Gezer:

To sum up: the phrase ‛Debir king of Eglon’ is, most probably, not the product of mere scribal miswriting but the product of a complicated process of combination, harmonization and revision of traditions, a process of which this part of the book of Joshua shows many signs, as commentators have seen. There were more relevant cities than the scheme of ‛five kings’ had room for. There was probably a serious tradition that took Adullam rather than Eglon as the place referred to several times. The variety of traditions still existing in the time of the LXX is shown by the list of (just over or under) thirty kings in ch. 12. The activity of creating names for persons of past history, sometimes using names of places for the purpose, is very likely. The very peculiar phrase ‛Debir king of Eglon’ is a result, and a sign, of these processes. (Barr 66)

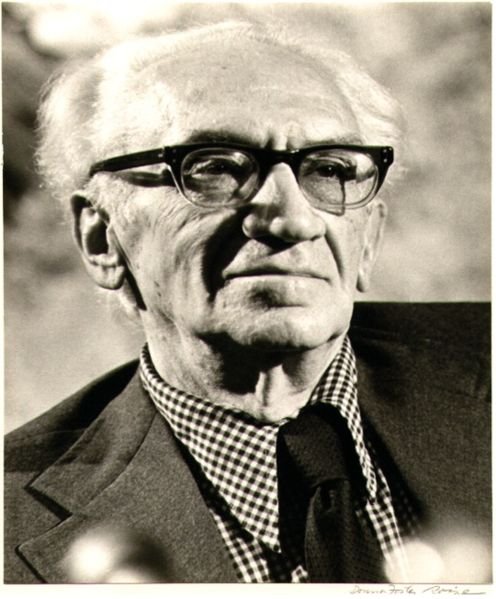

Worlds in Collision

In his iconic work Worlds in Collision, Immanuel Velikovsky took a literal, catastrophist view of this passage. He hypothesized that around the time of the Exodus from Egypt and the Conquest of Canaan—which he dated to 1474 and 1422 BCE respectively—Venus passed close to the Earth several times, causing catastrophic events. He also believed that close passages of Mars caused similar catastrophes between 776 and 687 BCE.

Several of Velikovsky’s disciples also believe that the Exodus and the Conquest took place against a backdrop of catastrophic events, but they have realigned these events with Velikovsky’s Mars catastrophe. Emmet Sweeney writes:

Moving into the Age of the Conquest and the Judges, when the Israelites battled with the natives of Canaan to possess and hold the land, the parallels with the Greek Mycenaean Age become almost too numerous to mention. Again, this is a topic I have dealt with at length elsewhere and am unable to repeat all the arguments here. Suffice to say that the major military innovations of the period of the Conquest and Judges, namely chariots, bronze swords, the composite bow and body armour, are all equally well associated with the high point of the Mycenaean/Heroic Age.

So, Moses and his epoch belongs squarely in the Age of Mars, the period which saw the final series of catastrophes associated with the god Mars and with his alter-ego Hercules. Velikovsky dated this period in the eighth century BC, an opinion shared by the present writer. (Emmet Sweeney)

Charles Ginenthal tentatively dated the Exodus to 763 BCE:

The position taken by this author, based on Velikovsky’s work (to be presented below) is that around 1500 B.C. the rotational axis of the Earth had moved from an eight or nine degree tilt to about fourteen to eighteen degrees. This would place the ancient river valley civilizations about ten and a half to five and a half degrees farther north than they are at present. They would be situated at a distance of about 730 to 380 miles north of where they are located today. After 800 B.C. an axial tilt caused by the Mars event would bring the tilt of the Earth to its present position. (Ginenthal 386-387)

While I am happy to accept that these events were accompanied by natural paroxysms and Klimasturz—sudden and dramatic climate change—I find it hard to believe that these paroxysms involved anything as earth-shattering as a pole shift. If the Earth had experienced a pole shift around the time of the Exodus, civilization would surely have been reset to the Stone Age.

My current attitude to Velikovskian catastrophism is that expressed by Albert Einstein in a letter to Velikovsky:

To the point, I can say in short: catastrophes yes, Venus no. (Einstein, Letter to Velikovsky 22 May 1954)

To which I would add: Catastrophes yes, Mars no. Whatever caused the catastrophes that have punctuated human history, I do not believe that wayward planets had anything to do with them.

If, however, we accept that within recorded history there were two “recent” epochs punctuated by catastrophist events—one around 1500 BCE and one around 750 BCE—is it possible that events associated with the earlier epoch were later incorrectly linked to the later epoch? Might the Biblical accounts of the Sun standing still on Gibeon and the hail of deadly meteorites at Azekah be misplaced memories of events that actually took place seven or eight centuries earlier?

The Five Kings of the Plain

In Genesis 14, another of the Old Testament’s best known stories is recounted:

And it came to pass in the days of Amraphel king of Shinar, Arioch king of Ellasar, Chedorlaomer king of Elam, and Tidal king of nations; That these made war with Bera king of Sodom, and with Birsha king of Gomorrah, Shinab king of Admah, and Shemeber king of Zeboiim, and the king of Bela, which is Zoar. All these were joined together in the vale of Siddim, which is the salt sea. Twelve years they served Chedorlaomer, and in the thirteenth year they rebelled. And in the fourteenth year came Chedorlaomer, and the kings that were with him, and smote the Rephaims in Ashteroth Karnaim, and the Zuzims in Ham, and the Emins in Shaveh Kiriathaim, And the Horites in their mount Seir, unto Elparan, which is by the wilderness. And they returned, and came to Enmishpat, which is Kadesh, and smote all the country of the Amalekites, and also the Amorites, that dwelt in Hazezontamar.

And there went out the king of Sodom, and the king of Gomorrah, and the king of Admah, and the king of Zeboiim, and the king of Bela (the same is Zoar;) and they joined battle with them in the vale of Siddim; With Chedorlaomer the king of Elam, and with Tidal king of nations, and Amraphel king of Shinar, and Arioch king of Ellasar; four kings with five. And the vale of Siddim was full of slimepits; and the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah fled, and fell there; and they that remained fled to the mountain. And they took all the goods of Sodom and Gomorrah, and all their victuals, and went their way.

And they took Lot, Abram’s brother’s son, who dwelt in Sodom, and his goods, and departed. And there came one that had escaped, and told Abram the Hebrew; for he dwelt in the plain of Mamre the Amorite, brother of Eshcol, and brother of Aner: and these were confederate with Abram. And when Abram heard that his brother was taken captive, he armed his trained servants, born in his own house, three hundred and eighteen, and pursued them unto Dan. And he divided himself against them, he and his servants, by night, and smote them, and pursued them unto Hobah, which is on the left hand of Damascus. And he brought back all the goods, and also brought again his brother Lot, and his goods, and the women also, and the people. And the king of Sodom went out to meet him after his return from the slaughter of Chedorlaomer, and of the kings that were with him, at the valley of Shaveh, which is the king’s dale.

And Melchizedek king of Salem brought forth bread and wine: and he was the priest of the most high God. And he blessed him, and said, Blessed be Abram of the most high God, possessor of heaven and earth: And blessed be the most high God, which hath delivered thine enemies into thy hand. And he gave him tithes of all. And the king of Sodom said unto Abram, Give me the persons, and take the goods to thyself. And Abram said to the king of Sodom, I have lift up mine hand unto the Lord, the most high God, the possessor of heaven and earth, That I will not take from a thread even to a shoelatchet, and that I will not take any thing that is thine, lest thou shouldest say, I have made Abram rich: Save only that which the young men have eaten, and the portion of the men which went with me, Aner, Eshcol, and Mamre; let them take their portion. (Genesis 14)

Like the story in Joshua 10, this story involves a coalition of five kings. It also has a king of Jerusalem called Melchizedek, a name curiously reminiscent of Adonizedek King of Jerusalem in Joshua 10. According to Velikovsky, Zedek was a Hebrew name for the planet Jupiter. The subsequent destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, which is described in Genesis 18-19, takes place during an earlier Velikovskian catastrophe. Velikovsky dated this particular catastrophe to the late third millennium BCE:

The destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah took place in historical times, according to my scheme in a catastrophe which caused also the end of the Old Kingdom in Egypt. (In the Beginning)

In the Short Chronology, however, this catastrophe was the one which occurred around 1500 BCE, at the end of the Younger Dryas. Sodom and Gomorrah were contemporary with pre-Dynastic Egypt.

Conclusion

Read literally—as Biblical Fundamentalists read it—the Book of Joshua ascribes the complete Conquest of Canaan to Joshua. In the Book of Judges, however, we read of later campaigns waged against the Canaanites by individual tribes of Israel. The truth may well be that there was indeed a historical Conquest of Canaan by a historical Joshua, but that it was far from complete. The task of finishing what Joshua began may have taken several generations:

The tenth chapter of the Book of Joshua begins by describing Israel’s defeat of a Canaanite coalition of five kings. It concludes with the description of a successful campaign against the Shephelah and hill country of that part of southern Palestine later occupied by the tribe of Judah. The first chapter of the Book of Judges, purporting to describe events which took place “after the death of Joshua” (1:1) appears to give a rather different picture of the Conquest, in which the individual tribes bear the responsibility for conquering their respective territories. The one describes a successful campaign of a united Israel under Joshua’s direction. The other, supported by statements in Joshua 15-19, indicates that the seizure of the Promised Land was a long process, accomplished not by a single great campaign but by a series of campaigns on the part of the individual tribes. (Wright 105)

Perhaps this is how the Dual Monarchy first came about: Joshua conquered Northern Canaan, and this territory became the Kingdom of Israel. Subsequently, the Tribe of Judah conquered Southern Canaan, and this territory became the Kingdom of Judah. This is just a piece of idle speculation on my part, but it is worth keeping in mind as we continue our research.

And that’s a good place to stop.

To be continued ...

References

- James Barr, Mythical Monarch Unmasked? Mysterious Doings of Debir King of Eglon, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, Volume 15, Issue 48, Pages 55-68, Sheffield Academic Press Limited, Sheffield (1990)

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 1, Forest Hills, NY (2003)

- Martin Noth, Das Buch Josua, J C B Mohr (Paul Siebeck), Tübingen (1938)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 1, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1904)

- G Ernest Wright, The Literary and Historical Problem of Joshua 10 and Judges 1, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Volume 5, Number 2, Pages 105-114, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1946)

Image Credits

- Joshua and the Five Captive Kings: Jacques-Joseph Tissot (artist), Jewish Museum, New York, Public Domain

- Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still upon Gibeon: John Martin (artist), National Gallery of art, Washington, DC, Public Domain

- The Five Cities of the Amorites: University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Jerusalem, D Survey, Great Britain War Office and Air Ministry (1960), Public Domain

- Joshua’s Victory over the Amorites: Nicolas Poussin (artist), Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Public Domain

- Immanuel Velikovsky: Donna Foster Roizen (photographer), © Frederic Jueneman, Creative Commons License

- The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah: John Martin (artist), Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle, Public Domain

- The Meeting of Abraham and Melchizedek: Peter Paul Rubens (artist), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Public Domain

Online Resources