In the Book of Joshua, we are told that in the wake of the destruction of Jericho and Ai, several Canaanite nations compacted an alliance and made preparations for war with the Israelites:

And it came to pass, when all the kings which were on this side Jordan, in the hills, and in the valleys, and in all the coasts of the great sea over against Lebanon, the Hittite, and the Amorite, the Canaanite, the Perizzite, the Hivite, and the Jebusite, heard thereof; That they gathered themselves together, to fight with Joshua and with Israel, with one accord. (Joshua 9:1-2)

One tribe of Hivites, however, decided that the better course of action was to come to terms with Joshua, using guile rather than arms to achieve a favourable settlement with the invaders:

And when the inhabitants of Gibeon heard what Joshua had done unto Jericho and to Ai, They did work wilily ... And they went to Joshua unto the camp at Gilgal, and said unto him, and to the men of Israel, We be come from a far country: now therefore make ye a league with us.

And the men of Israel said unto the Hivites, Peradventure ye dwell among us; and how shall we make a league with you?

And they said unto Joshua, We are thy servants.

And Joshua said unto them, Who are ye? and from whence come ye?

And they said unto him, From a very far country thy servants are come because of the name of the Lord thy God: for we have heard the fame of him, and all that he did in Egypt, And all that he did to the two kings of the Amorites, that were beyond Jordan, to Sihon king of Heshbon, and to Og king of Bashan, which was at Ashtaroth. Wherefore our elders and all the inhabitants of our country spake to us, saying, Take victuals with you for the journey, and go to meet them, and say unto them, We are your servants: therefore now make ye a league with us ...

And Joshua made peace with them, and made a league with them, to let them live: and the princes of the congregation sware unto them. (Joshua 9:3-11 ... 15)

In Joshua 9, the Gibeonites are identified as Hivites, but in 2 Samuel 21, they are said to be of the remnant of the Amorites.

The Gibeonites, we are told, comprised a tetrapolis in Canaan:

Now their cities were Gibeon, and Chephirah, and Beeroth, and Kirjathjearim. And the children of Israel smote them not, because the princes of the congregation had sworn unto them by the Lord God of Israel. (Joshua 9:17-18)

Does the archaeological evidence support this account? Were these cities sacked at the end of the Middle Bronze Age or beginning of the Late Bronze Age—which is where I place Joshua’s Conquest of Canaan—or were they spared the fate of other Canaanite cities such as Jericho and Ai?

Gibeon

The ruins of Gibeon lie on the outskirts of the Palestinian village of al-Jib, about 9 km NNW of Jerusalem. This identification is considered secure by most modern scholars. Although excavations at Gibeon began as early as 1956, the site has not yet been thoroughly explored:

Gibeon. The identification of El-Jib as the site of Gibeon seems assured, in terms of geography and general remains so far found. The limited excavations at the site have yielded first visitors in Middle Bronze I, a proper settlement for Middle Bronze II, eight Late Bronze Age tombs, then a walled township in Iron I-II. Given that 95 percent of the site remains undug, the possibility of a Late Bronze Age occupation (in the light of the tombs) remains open for future work to clarify. (Kitchen 189)

Kitchen placed Joshua’s conquest in LB II, whereas I place it at the end of MB II or the beginning of LB I. James B Pritchard of the University of Pennsylvania excavated the site between 1956 and 1962. He too sought for Joshua’s Gibeon at the end of the Late Bronze period, late in the thirteenth century [conventional chronology] (Pritchard 157):

Since Gibeon is described as “a great city” at this time, one would expect to find city walls and houses if the tradition preserved in the Book of Joshua is historically trustworthy. Yet traces of this city of the latter part of the Late bronze period have not come to light in the four seasons of excavations. (Pritchard 157)

If, however, we look for Joshua’s “great city” at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, we will not be disappointed:

During the Middle Bronze II period at Gibeon the material culture reached a level of artistic sophistication which is unique in the long history of the city ... Gibeon was evidently an independent city-state, free for a time from Egyptian domination during the period of the Hyksos rule in the Delta.

If the Gibeon of the Hyksos period may be termed sophisticated in its artistic attainments, particularly in ceramic forms, then it is appropriate to speak of its successor in the late bronze period as cosmopolitan. It is in this period, more than in any other of the city’s history, that one encounters a wide variety of imported artifacts from such distant points as Egypt in the south and Cyprus in the west. (Pritchard 155-156)

It is clear, then, that the city of Gibeon thrived both immediately before and immediately after the time of Joshua. The Middle Bronze II ended as the Hyksos were being expelled from Egypt and Ahmose I was establishing the 18th Dynasty. This is where I place the Exodus and the Conquest of Canaan. The city of Gibeon was in existence at this time, and Pritchard found clear evidence of continuity across the interface between MB II and LB I. This supports the Biblical account.

Chephirah

The ancient city of Chephirah is now identified with Khirbet Kefireh, a modern hilltop village about 12 km NW of Jerusalem, or 8 km WSW of Gibeon. The site of Khirbet Kefireh was surveyed several times in the 1970s, but extensive excavation is impossible due to the presence of modern habitations:

The surface survey has shown that Khirbet Kefireh was occupied continuously from the Iron Age II until the Byzantine Era and the early Islamic Period. Isolated potsherds from the Early Bronze Age and Iron I Age do not permit us to conclude that the site was occupied in these early epochs. We must then recognize clearly that we still lack definitive proof that Khirbet Kefireh is the Chephirah that existed prior to the establishment of the Israelite Monarchy. But its identification with the city of that name during and after the Monarchy poses no difficulty. (Vriezen 415)

Without more extensive excavation, we cannot say for certain whether the town existed at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, or, if it did, whether it was sacked or spared. Nevertheless, the presence of potsherds from the Early Bronze Age and the continued occupation of the site into the Middle Ages do nothing to refute the Biblical account, and might even be said to lend support to it.

Beeroth

The city of Beeroth is thought to have stood somewhere between Gibeon and Chephirah, approximately 10 km NW of Jerusalem. The name is Hebrew for wells. No ruins in this region have been identified with Beeroth and its location is still a matter of scholarly dispute. Several Palestinian villages in this region—including Bidu, Nabi Samwil and al-Qubeibah—have been identified with the Biblical Beeroth, but this seems to be little more than speculation.

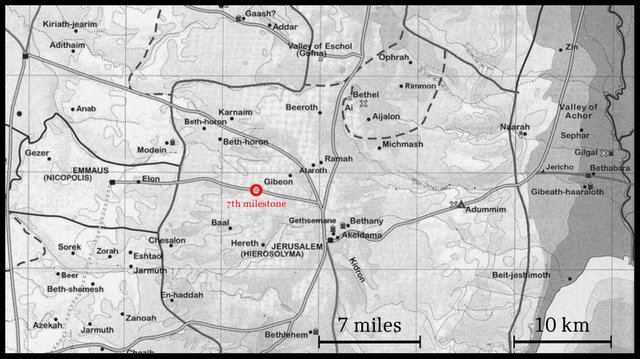

Eusebius’s Onomasticon places Beeroth at the seventh milestone from Jerusalem on the road to Nicopolis. If Nicopolis is the Biblical Emmaus, and Eusebius’s miles are Roman miles, then this would place Beeroth in the vicinity of Chephirah. More than this we cannot say.

Khirbat el-Burj, a tell close to the modern village of Beit Iksa, is another possible candidate. This hilltop site lies just to the west of the Golda Me’ir Boulevard, 1 km NE of Beit Iksa. Excavations have uncovered settlement remains from the Middle Bronze II and later periods.

Al Bireh, which lies 15 km N of Jerusalem, has also been proposed as a candidate—apparently on account of the similarity of the two names—and is so marked on the map above (Gauthier 2).

Clearly, there is too much uncertainty surrounding the location of Beeroth to allow any firm conclusions to be drawn.

Kirjathjearim

The fourth city of the Gibeonites, Kirjath-Jearim, is currently identified with Deir el-Azar, a hill situated in the town of Abu Ghosh, about 13 km west of Jerusalem. Eusebius places Kirjath-Jearim nine miles from Jerusalem, or a little more than 13 km:

The identification of the site of Kiriath-jearim with Deir el-ʽAzar—a large mound above the village of Abu Gosh, 13 km west of the Old City of Jerusalem—is secure, based on the following arguments:

In the description of the border between the inheritances of the tribes of Benjamin and Judah (Josh 15,8-10; 18,14-16) Kiriath-jearim is located south of Beth-horon (Beit Ur et-Tahta), north (in biblical terms, in fact, northeast) of Chesalon (Kesla, G.R. 154 132) and east of the Waters of Nephtoah (Lifta or Qaluniya).

According to Eusebius “there is a village Kiriathiareim on the way down to Diospolis], about 10 milestones from Ailia [Jerusalem]”. In another entry he puts it “between Ailia and Diospolis, lying on the road 9 milestones from Ailia”. Note that the Roman road from Jerusalem to Lod (Diospolis) passed immediately to the south of the hill.

The Arabic name of the site, Deir el-ʽAzar, seems to be a corruption of “The Monastery of Eleazar”, probably the name of the Byzantine monastery that commemorated the priest who was in charge of the Ark when it was kept at Kiriath-jearim (1 Sam 7,1).

The name Kiriath is preserved in the name of the village at the foot of the hill—Qaryat el-ʽInab (currently known as Abu Gosh). (Finkelstein & Römer 213-214)

Archaeological excavations of this site have only been ongoing for a few seasons. Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University and Thomas Römer and Christophe Nicolle of the Collège de France are the directors of the project. Little that is of interest to our query has yet been learnt other than that the site was occupied at the time of the Conquest of Canaan:

The site of Deir el-̔Azar was inhabited, probably continuously, from the Early Bronze to the Early Islamic period, but according to two archaeological surveys, a salvage excavation and our own work there, the main periods of activity were in the Iron IIB-C and the late Hellenistic and early Roman periods. (Finkelstein & Römer 215)

This, at least, does not undermine the Biblical account.

An alternative candidate for the Biblical Kirjath-Jearim is Khirbet Erma, a ruin about 17 km WSW of Jerusalem. This location, however, does not agree with Eusebius’s account and has received little support from the scholarly community.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Eusebius, The Onomasticon of Eusebius of Caesarea, Translated by G S P Freeman-Grenville, Carta, Jerusalem (2003)

- Israel Finkelstein, Thomas Römer, Kiriath-Jearim, Kiriath-Baal/Baalah, Gibeah: A Geographical-History Challeng, in Ido Koch, Thomas Römer & Omer Sergi (editors), Writing, Rewriting and Overwriting in the Books of Deuteronomy and Former Prophets, pp 211-222, Peeters Publishers, Leuven (2019)

- Henri Gauthier, Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques, Volume 2, La Société Royale de Géographie d’Égypte, Cairo (1925)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2003)

- James Bennett Pritchard, Gibeon, Where the Sun Stood Still: The Discovery of the Biblical City, Princeton University Press , Princeton, NJ (1962)

- Karel J H Vriezen, Chronique Archéologique (Fin), Revue Biblique, Volume 84, Number 3 (July 1977), pp 412–6, Peeters Publishers, Leuven (1977)

Image Credits

- The Ruins of Gibeon: © Natritmeyer, Creative Commons License

- The Pool of Gibeon: © Natritmeyer, Creative Commons License

- Khirbet Kefireh: Created by Funhistory with the consent of the original creator Karel J H Vriezen, Public Domain

- Khirbat el-Burj: © יהונתן הימן, Fair Use

- Map of Jerusalem and Environs after the Onomasticon of Eusebius: After S Notley & Z Safrai, Eusebius, Onomasticon: The Place Names of Divine Scripture, Jewish and Christian Perspectives, Number 9, Brill, Leiden (2005), Fair Use

- Kirjath-Jearim: © William Schlegel, Satellite Bible Atlas, Fair Use

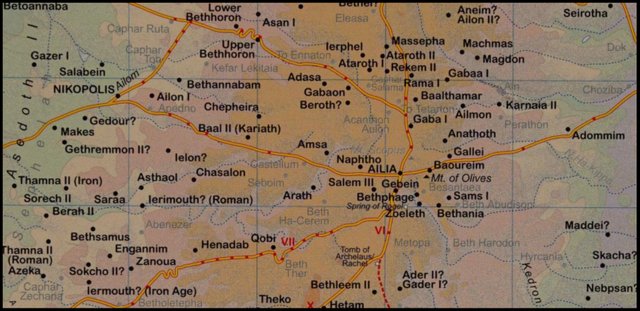

- Map of Judea after the Onomasticon of Eusebius, The Onomasticon of Eusebius of Caesarea, Translated by G S P Freeman-Grenville, Map 7, Carta, Jerusalem (2003), Fair Use