In the last two articles, we looked at the opinions of two Biblical scholars—Kenneth A Kitchen and James K Hoffmeier—concerning the historicity of Joshua and the Conquest of Canaan. Although the majority view among scholars today is that the events depicted in the Book of Joshua are not historical and that no reliance can be placed on them, I believe that Kitchen and Hoffmeier have established a prima facie case for a military invasion of Canaan as depicted in the first eleven chapters of Joshua.

In their search for archaeological evidence for the Conquest, Kitchen and Hoffmeier have focused on the Late Bronze Age. Both identify Ramesses II of the 19th Dynasty as the Pharaoh of the Exodus. I, however, believe that the Exodus took place at the beginning of the 18th Dynasty, when the Hyksos were being expelled from Egypt. This places the Conquest of Canaan at the end of the Middle Bronze Age or during the earliest phase of the Late Bronze Age, about two centuries before the death of Ramesses. In the model of the Short Chronology to which I subscribe, the absolute date for the Conquest is around 760 BCE.

Transjordan

In the opening chapter of the Book of Joshua, we are told explicitly that the tribes of Reuben and Gad and the half-tribe of Manasseh also took part in the conquest, even though their territories on the eastern side of the Jordan had already been conquered by Moses:

And to the Reubenites, and to the Gadites, and to half the tribe of Manasseh, spake Joshua, saying, Remember the word which Moses the servant of the Lord commanded you, saying, The Lord your God hath given you rest, and hath given you this land. Your wives, your little ones, and your cattle, shall remain in the land which Moses gave you on this side Jordan; but ye shall pass before your brethren armed, all the mighty men of valour, and help them; Until the Lord have given your brethren rest, as he hath given you, and they also have possessed the land which the Lord your God giveth them: then ye shall return unto the land of your possession, and enjoy it, which Moses the Lord’s servant gave you on this side Jordan toward the sunrising. (Joshua 1:12-15)

I believe, however, that the Israelite Conquest of Transjordan followed the Conquest of Canaan. This is a subject to which I shall return in a later article. In the meantime, let us concentrate on the Conquest of Canaan.

Reconnaissance

At the close of the Book of Deuteronomy, the Israelites were encamped in the Plains of Moab, in Transjordan:

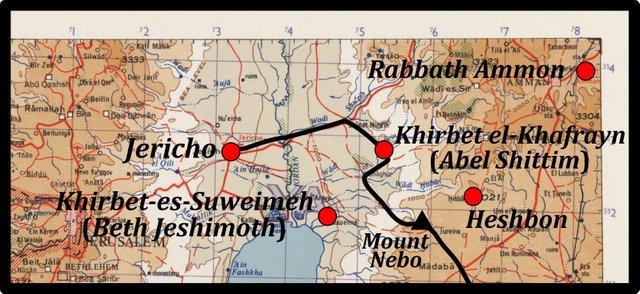

And they removed from Almondiblathaim, and pitched in the mountains of Abarim, before Nebo. And they departed from the mountains of Abarim, and pitched in the plains of Moab by Jordan near Jericho. And they pitched by Jordan, from Bethjesimoth even unto Abelshittim in the plains of Moab. (Numbers 33:47-49)

In as earlier article, we identified the Mountains of Abarim with Mount Nebo. As for the Plains of Moab, the location of Jericho is undisputed, and the valley of the River Jordan has hardly shifted since the days of the Old Testament. The plains of Moab on this side Jordan by Jericho (Numbers 22:01) can be easily identified on a modern map of the region.

And what of Bethjesimoth and Abelshittim, the extreme points of the area occupied by the Israelites? We saw that there are good candidates for these two toponyms. Bethjesimoth has been identified with Khirbet-es-Suweimeh, while Abelshittim is believed to be the same place as Shittim, or Ha-Shittim, which is mentioned elsewhere in the Bible. Shittim is now widely identified with Abila in Transjordan, an ancient city about 20 km east of Jericho. Abila is identified with the modern Khirbet el-Kafrayn or the nearby archaeological site of Tell el-Hammam.

It is debatable whether there were enough Israelites to occupy all the land between Bethjesimoth and Abelshittim—a distance of about 10 km. I suspect that later scholars realized that if there had been over 600,000 Israelites (Numbers 1:46), their encampment would have occupied a considerable area. But if we set aside such an extravagant number, and instead restrict the total number of Israelites to a few thousand, then there is no reason why they could not all have been encamped at Abelshittim.

And that this was the original version of the story seems to be confirmed by the Book of Joshua:

And Joshua the son of Nun sent out of Shittim two men to spy secretly, saying, Go view the land, even Jericho. (Joshua 2:1a)

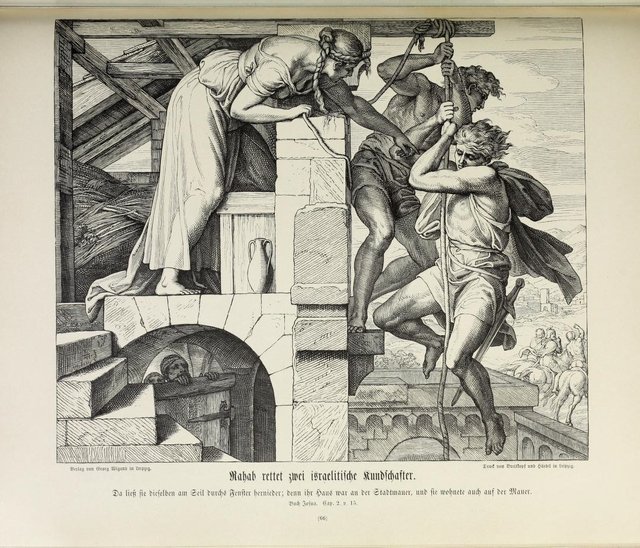

The episode of the two spies is something of a mystery. According to Joshua 2, a prostitute called Rahab hid the spies when the King of Jericho learnt of their presence and demanded that they be handed over. She then facilitated their escape, in return for which she and her family were spared when Joshua subsequently sacked Jericho (Joshua 6:22-25).

The ancient city of Jericho lay about 22 km west of Shittim, on the other side of the River Jordan. The two spies are not named in the Bible, but traditionally they have been identified as Caleb and Phinehas, two men who feature elsewhere in the story of the Exodus (Ginzberg 4:4-5):

Caleb, the son of Jephunneh, was one of the twelve spies sent by Moses from Kadesh-Barnea to reconnoitre the land of Canaan. When the spies returned, he and Joshua were the only two who urged Moses to proceed with the invasion.

Phinehas was the grandson of Aaron and the son of Eleazar, both High Priests of Israel. He demonstrated his zeal during the Heresy of Peor, an episode that took place during the sojourn at Shittim.

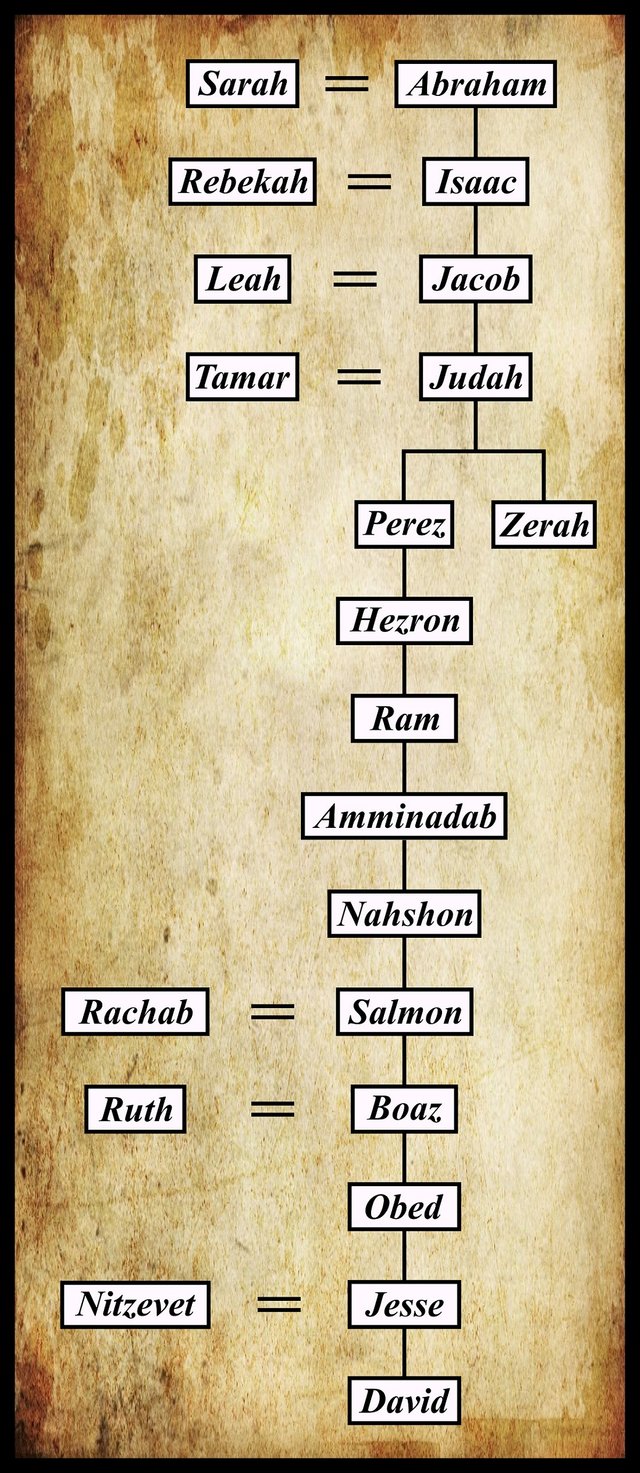

Another tradition identifies the two spies as Perez and Zerah, the sons of Judah, while a third names them as Kenaz and Seenamias, the two sons of Caleb (Ginzberg 6:171).

Curiously, when Rahab hides the spies, the Biblical text says: she hid him (ותצפנו, watizpeno). Various attempts have been made to explain this: for example, some rabbinical scholars have suggested that Phinehas made himself invisible, so that only Caleb had to be hidden. A simpler explanation is that there was only one spy in the original version of the story. Perhaps the second spy was added later so that there would be two virtuous spies, just as there had been two virtuous spies among the twelve that Moses dispatched from Kadesh-Barnea.

Later traditions claim that Rahab subsequently married Joshua and that several prominent figures in the subsequent history of Israel were numbered among their descendants: the prophet Jeremiah, his scribe Baruch, the prophetess Huldah, and the prophet Ezekiel among them (Ginzberg 4:5, 6:171). Matthew 1:5 preserves another tradition, according to which Ruth’s husband Boaz—the great-grandfather of David—was the son of Salmon and Rachab.

None of the intelligence acquired by the two spies is subsequently used by Joshua to compass the downfall of Jericho. Although the spies report that the Canaanites are terrified of the Israelites, the entire incident could be removed without doing any harm to the overall narrative of Joshua’s Conquest. So what purpose does this episode serve? Rabbinical scholars have drawn numerous moral lessons from it, as one would expect, but perhaps it is included because it actually happened. It is only natural that Joshua should have sent out spies to gather intelligence before embarking on the invasion. Perhaps these spies really were sheltered by an inhabitant of Jericho, whose life was subsequently spared as a reward for the risks she was willing to take for the Israelites.

Whatever the truth, there is little doubt that the tale grew in the telling, and many of the interesting details in the story—hiding the spies on the roof under stalks of flax, letting them down the city wall by a rope, the use of scarlet thread to mark Rahab’s house—were probably added at a later date. But even if the entire episode is a fabrication, it does not follow that the siege and destruction of Jericho were also made up.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 4, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1913)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 6, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1928)

- James K Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2003)

Image Credits

- The Two Spies Escape from Rahab’s House: Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Die Bibel in Bildern, Georg Wigand’s Verlag, Leipzig (1860), Public Domain

- Canaan after the Conquest: Charles John Ellicott (editor), An Old Testament Commentary for English Readers, Volume 2, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co, London (1883), Public Domain

- Map of the Plains of Moab: University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Jerusalem, D Survey, Great Britain War Office and Air Ministry (1960), Public Domain

- Tell el-Hammam (Shittim): © Deg777, Creative Commons License

- Rahab’s Window: © Gail Wallace, Fair Use