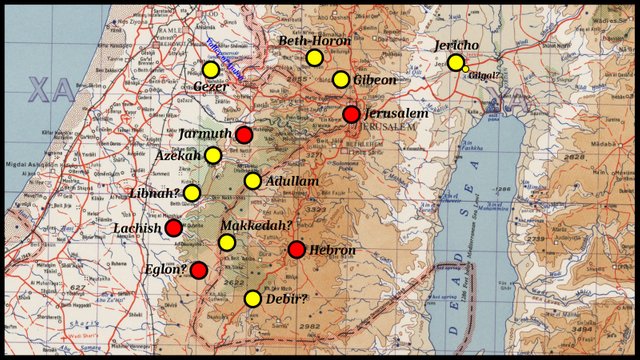

In Joshua 10:28-43 Joshua’s campaign in southern Canaan is briefly described. After the capture and execution of the five kings of the Amorites, the Israelites turn their attention to their cities:

And that day Joshua took Makkedah, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and the king thereof he utterly destroyed, them, and all the souls that were therein; he let none remain: and he did to the king of Makkedah as he did unto the king of Jericho. Then Joshua passed from Makkedah, and all Israel with him, unto Libnah, and fought against Libnah: And the Lord delivered it also, and the king thereof, into the hand of Israel; and he smote it with the edge of the sword, and all the souls that were therein; he let none remain in it; but did unto the king thereof as he did unto the king of Jericho. And Joshua passed from Libnah, and all Israel with him, unto Lachish, and encamped against it, and fought against it: And the Lord delivered Lachish into the hand of Israel, which took it on the second day, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and all the souls that were therein, according to all that he had done to Libnah.

Then Horam king of Gezer came up to help Lachish; and Joshua smote him and his people, until he had left him none remaining. And from Lachish Joshua passed unto Eglon, and all Israel with him; and they encamped against it, and fought against it: And they took it on that day, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and all the souls that were therein he utterly destroyed that day, according to all that he had done to Lachish. And Joshua went up from Eglon, and all Israel with him, unto Hebron; and they fought against it: And they took it, and smote it with the edge of the sword, and the king thereof, and all the cities thereof, and all the souls that were therein; he left none remaining, according to all that he had done to Eglon; but destroyed it utterly, and all the souls that were therein.

And Joshua returned, and all Israel with him, to Debir; and fought against it: And he took it, and the king thereof, and all the cities thereof; and they smote them with the edge of the sword, and utterly destroyed all the souls that were therein; he left none remaining: as he had done to Hebron, so he did to Debir, and to the king thereof; as he had done also to Libnah, and to her king. So Joshua smote all the country of the hills, and of the south, and of the vale, and of the springs, and all their kings: he left none remaining, but utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the Lord God of Israel commanded.

And Joshua smote them from Kadeshbarnea even unto Gaza, and all the country of Goshen, even unto Gibeon. And all these kings and their land did Joshua take at one time, because the Lord God of Israel fought for Israel. And Joshua returned, and all Israel with him, unto the camp to Gilgal. (Joshua 10:28-43)

This account of Joshua’s Southern Campaign contradicts some of the elements of the preceding account of the Five Kings of the Amorites:

In Joshua 10:3, Debir is the King of Eglon. But in Joshua 10:38-39, Debir is a city in southern Canaan.

In Joshua 10:26, Joshua executes the five kings of Jerusalem, Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish, and Eglon. But in Joshua 10:36-37, Joshua kills the King of Hebron during the subsequent capture of his city.

In his Southern Campaign, Joshua does not attack Jerusalem or Jarmuth, even though the kings of those two cities were among the Five Kings of the Amorites executed in Joshua 10:26.

The Southern Campaign also engulfs a number of cities that were not mentioned before: Libnah, Gezer, Kadeshbarnea, Gaza, and Goshen. While this does not flatly contradict the earlier account of the campaign, it is inconsistent with it.

Clearly, we have here an account that was constructed using at least two independent sources, and errors were made when they were conflated to produce a continuous narrative. This ineluctable conclusion should put us on our guard when we come to assess the historicity of Joshua’s Southern Campaign.

Archaeology

In this series of articles, I have adopted as my working hypothesis a chronological model in which the Exodus was a historical event that occurred at the time of the Expulsion of the Hyksos from Egyptian—that is, at the end of the Middle Bronze Age and the beginning of the 18th Dynasty. According to the mainstream chronology, these events occurred sometime between 1550 and 1500 BCE. But the Short Chronology places them much later—763 BCE according to the working model I am using. In this model, the Conquest of Canaan by Joshua took place around 760 BCE.

So what does the archaeology have to say about Joshua’s Southern Campaign? Is there evidence of a large-scale military campaign being waged in southern Canaan at the beginning of the Late Bronze Age?

Destruction layers dating to the end of the Middle Bronze Age and the beginning of the Late Bronze Age have been found on some thirty sites in Palestine. (Grabbe 159)

Grabbe’s source for this piece of information is James M Weinstein’s 1981 paper The Egyptian Empire in Palestine: A Reassessment. In this paper, Weinstein investigates the common assumption that this destruction was the work of the Egyptians:

That the Egyptians were responsible for most if not all the destructions of the MB cities of Palestine has long been a basic assumption in virtually all reconstructions of Palestinian history and archaeology of this period. Now, however, at least two scholars have brought even this supposition into doubt. Redford (1979: 273) has asserted that the early 18th-Dynasty campaigns, being limited to only one or two per reign, could not have been responsible for so many destructions, while Shea has claimed that “there is very little inscriptional evidence from Egypt to indicate that the Egyptians had anything to do with these destructions” (Shea1979: 3), and so “some other explanation for the destructions of these sites should therefore be sought” (Shea 1979: 4). (Weinstein 1-2)

If the Egyptians were not responsible, the Israelites might have been. But of the thirty Palestinian sites considered by Weinstein, only Lachish and Gezer figure in Joshua’s Southern Campaign. If Lachish was destroyed at the beginning of the Late Bronze Age, it must have been quickly resettled, as it sent an envoy to Amenhotep II in Thebes during LB IB (Weinstein 13). As for Gezer, the fiery destruction of Stratum XVIII is generally dated to the reign of Amenhotep I or Thutmose I, if not later—possibly too late for our dating of Joshua’s Campaign of Conquest (Weinstein 4). Moreover, Joshua 10 does not claim that Gezer was attacked by the Israelites, only that its king and people were routed when they came to the aid of Lachish.

Tell el-Hesi is also included in Weinstein’s list of thirty sites. This tell has been identified in the past with both Lachish and Eglon, but both of these identifications are now considered unlikely. Lachish is now sought at Tell ed-Duweir (Tel Lachish) and Eglon at Tell ‛Eton.

Weinstein comes down firmly on the side of the mainstream archaeologists. In his opinion, the Egyptians were responsible for the destruction of these thirty cities during their campaign to root out the Hyksos from Canaan once and for all (Weinstein 8). Whatever the truth, the archaeological evidence does not lend much support to the historicity of Joshua’s Southern Campaign as described in the Book of Joshua.

Cardinal Points

In Joshua 10:40-41, we are told of the culmination of Joshua’s Southern Campaign:

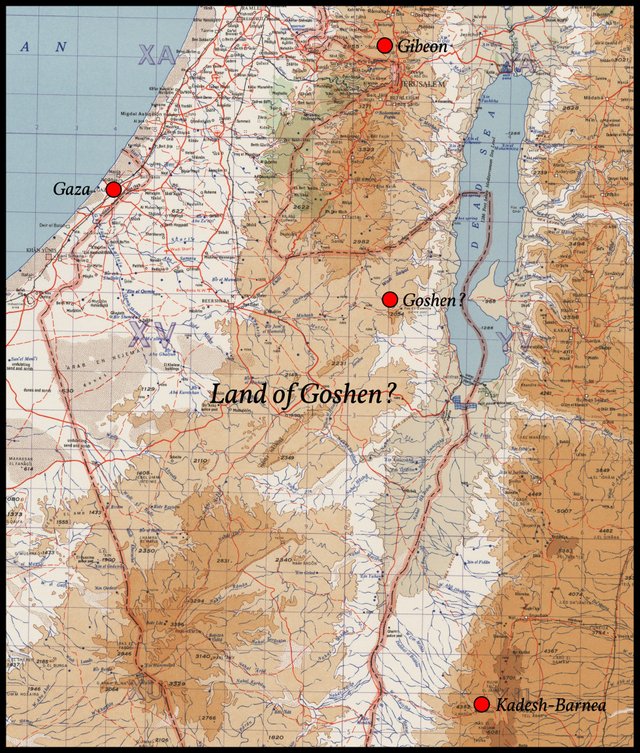

So Joshua smote all the country of the hills, and of the south, and of the vale, and of the springs, and all their kings: he left none remaining, but utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the Lord God of Israel commanded. And Joshua smote them from Kadeshbarnea even unto Gaza, and all the country of Goshen, even unto Gibeon. (Joshua 10:40-41)

These four locations, I believe, represent the extreme cardinal points of the area encompassed by Joshua’s Southern Campaign: And Joshua smote them from Kadeshbarnea in the east to Gaza in the west, and from Goshen in the south to Gibeon in the north.

This supports our earlier identification of Kadesh-Barnea with Petra, which lies far to the east of Gaza. The commonest identification of Kadesh-Barnea is with the present-day Tell el-Qudeirat, which lies south of Gaza.

Goshen’s location is unknown. Some early scholars identified it with the Land of Goshen in Egypt (see Clarke 51), where the House of Israel dwelt before the Exodus, but this is surely untenable. The only candidate I have come across is Sekiyeh, which lies about 65 km south of Jerusalem. This would make it an ideal location for the southern extremity of Joshua’s campaign. The country of Goshen, as it is expressed in Joshua 10:41, has also been identified with a broader region in the north of the Negev Desert (Berlin & Brettler 483).

In conclusion, I am inclined to believe that the conquest of southern Canaan was a lengthy process undertaken by a later generation of Israelites, long after Joshua’s death and his successful conquest of the north. As I suggested in an earlier article, this scenario could explain how the Dual Monarchy of Israel and Judah first arose. The northern territory conquered by Joshua became the Kingdom of Israel. Later, the Tribe of Judah conquered southern Canaan and established a rival Kingdom of Judah.

There is little decisive evidence in support of the hypothesis that Joshua campaigned in southern Canaan at the beginning of the Late Bronze Age. The identities of several of the cities mentioned in Joshua 10 are still disputed, however, so this conclusion is by no means certain.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), The Jewish Study Bible, Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Adam Clarke, The Holy Bible ... With a Commentary and Critical Notes, Volume 2, G Lane & P P Sandford, New York (1843)

- Lester L Grabbe (editor), The Land of Canaan in the Late Bronze Age, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, London (2016)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2003)

- James M Weinstein, The Egyptian Empire in Palestine: A Reassessment, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Volume 241, Pages 1–28, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1981)

Image Credits

- Tel Burna (Libnah?): Joeuziel (photographer), Public Domain

- Joshua’s Southern Campaign: University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Jerusalem, D Survey, Great Britain War Office and Air Ministry (1960), Public Domain

- Lachish (City Gate): © Wilson44691, Creative Commons License

- The Limits of Joshua’s Southern Campaign: University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Jerusalem, D Survey, Great Britain War Office and Air Ministry (1960), Public Domain