In the Book of Judges, the eleventh Judge of Israel is Abdon, another of the minor judges. Only three verses are devoted to his judgeship:

And after [Elon] Abdon the son of Hillel, a Pirathonite, judged Israel. And he had forty sons and thirty nephews, that rode on threescore and ten ass colts: and he judged Israel eight years. And Abdon the son of Hillel the Pirathonite died, and was buried in Pirathon in the land of Ephraim, in the mount of the Amalekites. (Judges 12:13-15)

The reference to his forty sons and thirty nephews (literally sons of sons, meaning grandsons) riding on seventy ass colts is suspiciously similar to the account of the seventh judge, Jair:

And after him arose Jair, a Gileadite, and judged Israel twenty and two years. And he had thirty sons that rode on thirty ass colts, and they had thirty cities, which are called Havothjair unto this day, which are in the land of Gilead. (Judges 10:3-4)

Another minor judge, Ibzan, had thirty sons and thirty daughters (Judges 12:9).

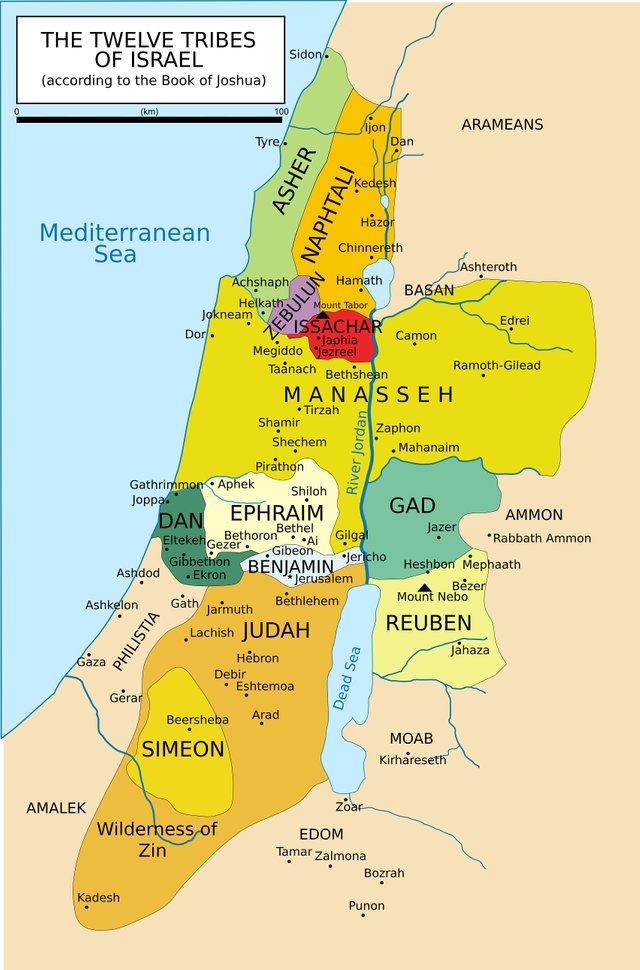

In the last article, we saw that the name of the tenth judge, Elon, occurs in the Bible as both a personal name and the name of a place. The same is true of Abdon, which is also the name of one of the thirteen Levitical cities assigned to the family of Gershon. Abdon is in the territory of the Tribe of Asher:

And the children of Israel gave unto the Levites out of their inheritance, at the commandment of the Lord, these cities and their suburbs ...

And unto the children of Gershon, of the families of the Levites, out of the other half tribe of Manasseh they gave Golan in Bashan with her suburbs, to be a city of refuge for the slayer; and Beeshterah with her suburbs; two cities.

And out of the tribe of Issachar, Kishon with her suburbs, Dabareh with her suburbs, Jarmuth with her suburbs, Engannim with her suburbs; four cities.

And out of the tribe of Asher, Mishal with her suburbs, Abdon with her suburbs, Helkath with her suburbs, and Rehob with her suburbs; four cities.

And out of the tribe of Naphtali, Kedesh in Galilee with her suburbs, to be a city of refuge for the slayer; and Hammothdor with her suburbs, and Kartan with her suburbs; three cities.

All the cities of the Gershonites according to their families were thirteen cities with their suburbs. (Joshua 21:3 ... 27-33 : I Chronicles 6)

Abdon has been identified with Khirbet ’Abda, or Tel Avdon, an archaeological tell in northern Israel. A modern Israeli village or moshav that was established nearby was given the name Avdon. The earliest remains at Khirbet ’Abda may only go back to the Late Bronze Age (Freedman 129). According to the Archaeological Survey of Israel, however, the site was first settled in the Middle Bronze Age II. Abdon the Judge is said to be a native of the Land of Ephraim, which lies much further south.

In I Samuel 12, Samuel names four Judges of Israel:

And the Lord sent Jerubbaal, and Bedan, and Jephthah, and Samuel, and delivered you out of the hand of your enemies on every side, and ye dwelled safe. (I Samuel 12:11)

Bedan is believed to refer to Abdon, though earlier scholars assumed that it referred to Samson, who was of the Tribe of Dan (McClintock & Strong 8, 716).

Legends

Although we are told little of the Judgeship of Abdon in the Book of Judges, some traditions survive that record his exploits. In The Legends of the Jews, Louis Ginzberg has collated these. Here, Abdon is described as the immediate successor of Jephthah and predecessor of Elon:

As it had been Jephthah’s task to ward off the Ammonites, so his successor Abdon was occupied with protecting Israel against the Moabites. The king of Moab sent messengers to Abdon, and they spoke thus: “Thou well knowest that Israel took possession of cities that belonged to me. Return them.” Abdon’s reply was: “Know ye not how the Ammonites fared? The measure of Moab’s sins, it seems, is full.” With his army of twenty thousand men he went out against the enemy, slew forty-five thousand of their number, and routed the rest. (Ginzberg 4:46-47)

This account is taken from Pseudo-Philo’s Biblical Antiquities, which was probably written sometime in the 1st or 2nd century CE (Ginzberg 6:204, James 194). As Ginzberg notes, Josephus’s account of the Judgeship of Abdon is at odds with this (Ginzberg 6:204):

Abdon, also, the son of Hillel, of the tribe of Ephraim, and born at the city Pyrathon, was ordained their supreme governor after Helon. He is only recorded to have been happy in his children; for the public affairs were then so peaceable, and in such security, that neither did he perform any glorious action. He had forty sons, and by them left thirty grand-children; and he marched in state with these seventy, who were all very skilful in riding horses, and he left them all alive after him. He died an old man; and obtained a magnificent burial in Pyrathon. (Josephus & Havercamp 348-349)

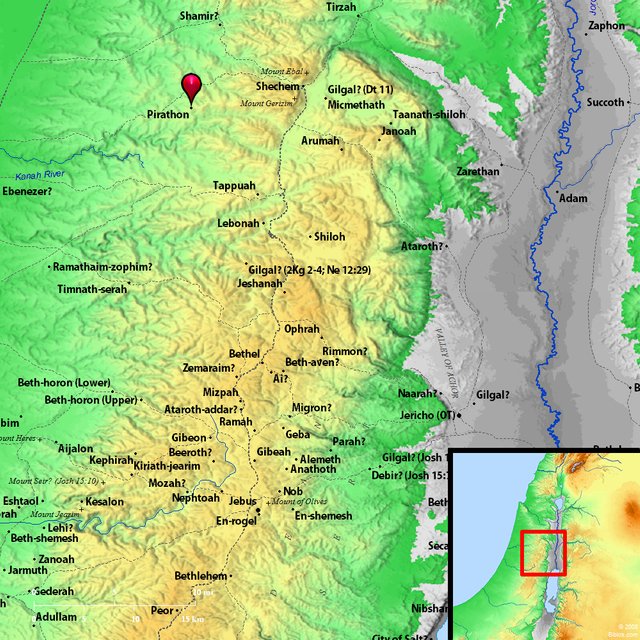

Pirathon

Abdon’s native city of Pirathon is now generally identified with the modern Fara’ata, which lies about 10 km southwest of Nablus (ancient Shechem) (Freedman 6989). Opponents of this view point out that the name Ferảta is not testified before the 14th century:

It is mentioned in the fourteenth century by its present name, and has been thought to be the ancient Pirathon, but the Samaritan Chronicle (dating from the twelfth century), gives its ancient name as Ophrah, which suggests its being Ophrah of Abiezer [Judges 6:11] (Conder & Kitchener 162-163).

Ophrah, you may recall, was the home of Gideon, Fifth Judge of Israel. It too has been identified with Fara’ata. Another problem with the identification of Pirathon with Fara’ata is that Pirathon lay in the territory of the Tribe of Ephraim, whereas Fara’ata is in Manasseh. Fara’ata is located to the north of the Wai Qana (Kanah), which forms part of the boundary between Manasseh and Ephraim:

And the coast of Manasseh was from Asher to Michmethah, that lieth before Shechem; and the border went along on the right hand unto the inhabitants of Entappuah. Now Manasseh had the land of Tappuah: but Tappuah on the border of Manasseh belonged to the children of Ephraim; And the coast descended unto the river Kanah, southward of the river: these cities of Ephraim are among the cities of Manasseh: the coast of Manasseh also was on the north side of the river, and the outgoings of it were at the sea: Southward it was Ephraim’s, and northward it was Manasseh’s, and the sea is his border; and they met together in Asher on the north, and in Issachar on the east. (Joshua 17:7-10)

In the Biblical Antiquities Pseudo-Philo says that Abdon was buried in Ephrata his city (James 194). Could this mean that Pirathon and Ephrata were different names for the same city? Ephrath was another name for Bethlehem, which is in Judah, not hill country of Ephraim. In an earlier article we saw that there was also a Bethlehem in the territory of Zebulun. Ibzan, the Ninth Judge of Israel, was a native of this Bethlehem and was buried there. But Zebulun is too far north and Judah is too far south.

Freedman points that the gentilic form of Ephraim (ie Ephraimites) has a similar spelling in Hebrew to Ephrathah, but that this is just an etymological coincidence (Freedman 493). This gentilic form actually occurs in this very chapter—Judges 12:5, in the well-known Shibboleth story. Pseudo-Philo calls Abdon Addo the son of Elech of Praton, butchering all three names, so perhaps we should not set great store by his Ephrata.

Last Judge of Israel?

Although Abdon is followed by Samson, whose story is also told in the Book of Judges, there is a very real sense that his Judgeship marks an important epoch in the history of the Israelites:

A certain importance attaches to Abdon from the fact that he is the last judge mentioned in the continuous account (Judges 2:6–13:1) in the Book of Judges. After the account of him follows the statement that Israel was delivered into the hands of the Philistines forty years, and with that statement the continuous account closes and the series of personal stories begins—the stories of Samson, of Micah and his Levite, of the Benjamite civil war, followed in our English Bibles by the stories of Ruth and of the childhood of Samuel. With the close of this last story (I Samuel 4:18) the narrative of public affairs is resumed, at a point when Israel is making a desperate effort, at the close of the forty years of Eli, to throw off the Philistine yoke. A large part of one’s views of the history of the period of the Judges will depend on the way in which he combines these events. My own view is that the forty years of Judges 13:1 and of I Samuel 4:18 are the same; that at the death of Abdon the Philistines asserted themselves as overlords of Israel; that it was a part of their policy to suppress nationality in Israel; that they abolished the office of judge, and changed the high-priesthood to another family, making Eli high priest; that Eli was sufficiently competent so that many of the functions of national judge drifted into his hands. It should be noted that the regaining of independence was signalized by the reestablishment of the office of judge, with Samuel as incumbent (I Samuel 7:6 and context). This view takes into the account that the narrative concerning Samson is detachable, like the narratives that follow, Samson belonging to an earlier period. (Orr 4)

Kenneth Kitchen suggests that Abdon may have been a contemporary of Samuel:

From Table 14 we have the sequence of “recognized” judges back from Abdon to Jephthah. Eli was not a tribal judge but a Levitical priest at the (post)tabernacle sanctuary at Shiloh. And Samuel, his spiritual successor, was a prophet and kept normally to the very narrow circuit of Bethel, Gilgal, Mizpah, and home to Ramah (1 Sam. 7:15-16), where people might consult him. Thus the last-named tribal judge, Abdon, may have been his nonreligious contemporary, whose role was in practice supplanted by the monarchy of Saul (who replaced all “judges”). (Kitchen 208)

Conclusion

In my study of the Book of Judges I have consistently suggested that any historical content of this book probably refers to a period before the Joshuan Conquest of Canaan, when the House of Israel was still in Egypt. This dating is supported by the reference in this chapter to Pirathon lying in the land of Ephraim, in the mount of the Amalekites. The Amalekites ought to have been driven out of Canaan by this date, in accordance with God’s prophecy in Deuteronomy:

Remember what Amalek did unto thee by the way, when ye were come forth out of Egypt; How he met thee by the way, and smote the hindmost of thee, even all that were feeble behind thee, when thou wast faint and weary; and he feared not God. Therefore it shall be, when the Lord thy God hath given thee rest from all thine enemies round about, in the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee for an inheritance to possess it, that thou shalt blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven; thou shalt not forget it. (Deuteronomy 17-19)

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Claude Regnier Conder & Horatio Herbert Kitchener, The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archæology, Volume 2, Sheets 7-16, The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London (1882)

- David Freedman (editor-in-chief), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, Doubleday, New York (1992)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 4, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1913)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 6, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1928)

- Montague Rhodes James (translator), The Biblical Antiquities of Philo, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London (1917)

- Flavius Josephus, Syvert Havercamp (translator), Complete Works of Josephus, Volume 1, Bigelow, Brown & Co, Inc, New York (1800)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan (2003)

- John McClintock, James Strong, Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 1, Harper & Brothers, New York (1880)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 1, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

Image Credits

- Abdon: Bartholomaeus Gaius, Epitome Historico-Chronologica Gestorum Omnium Patriarcharum, etc, Number 48, Giovanni Generoso Salomoni, Rome (1751), Public Domain

- Elon and Abdon: After Jan Snellinck (artist), Gerard de Jode, Thesaurus Sacrarum historiarum Veteris et Novi Testamenti, Folio 95r, Antwerp (1585), Public Domain

- Tel Avdon: © בייבלווקס (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Louis Ginzberg: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- The Twelve Tribes of Israel: © Janz (designer), Creative Commons License

- Pirathon?: © BibleHub (designer using BibleMapper), Fair Use