The fourth Judge of Israel was the prophetess Deborah, one of the best known characters in the Bible. Her story is recounted in the fourth and fifth chapters of the Book of Judges.

After the death of Ehud, the Israelites are oppressed for twenty years by Jabin, the king of Canaan, who reigns from the city of Hazor.

Deborah, the wife of Lapidoth, becomes Judge of Israel. She delivers her judgements from beneath a palm tree between Ramah and Bethel in mount Ephraim.

Deborah commands her general, Barak son of Abinoam of Kedesh Naphtali, to march an army of ten thousand men from Naphtali and Zebulun to Mount Tabor, overlooking the Plain of Esdraelon. He agrees only on condition that she accompany him. She accepts this condition, but prophesies that the honour of defeating the Canaanites will fall to a woman.

Jabin’s general, Sisera, from Harosheth Haggoyim (Smithy of the Nations), marches with an army of 900 iron chariots and a multitude of troops to the River Kishon.

Heber the Kenite, a descendant of Moses’ father-in-law Hobab, informs Sisera that the Israelites have mustered on Mount Tabor. Heber lives in the Plain of Zaanaim, which is near Kedesh Naphtali.

In the ensuing battle, Sisera is routed.

Sisera escapes on foot. His army is pursued as far as Harosheth Haggoyim, where it is destroyed.

Sisera comes to the tent of Jael, the wife of Heber, and lies down to rest. She gives him milk to drink, and while he is asleep she hammers a tent-pin through his temple. Deborah’s prophesy is fulfilled and the honour of defeating the Canaanites redounds to Jael, even though she desecrated the sanctuary of her own home by murdering a guest.

After the battle, there is peace in the land for forty years.

Chapter 5 of the Book of Judges comprises the Song of Deborah, a victory hymn sung by Deborah and Barak:

... although these chapters [Judges 4 and 5] agree in some details, the differences between the two are so great as to make it necessary to treat them separately. (Singer 489)

Based on its grammar and context, some scholars have identified the Song of Deborah as one of the oldest passages in the Bible, but this has been disputed recently.

The story of Deborah and her Judgeship is replete with details and proper names, which scholars have used to assess the historicity of the story and its characters.

Dramatis Personae

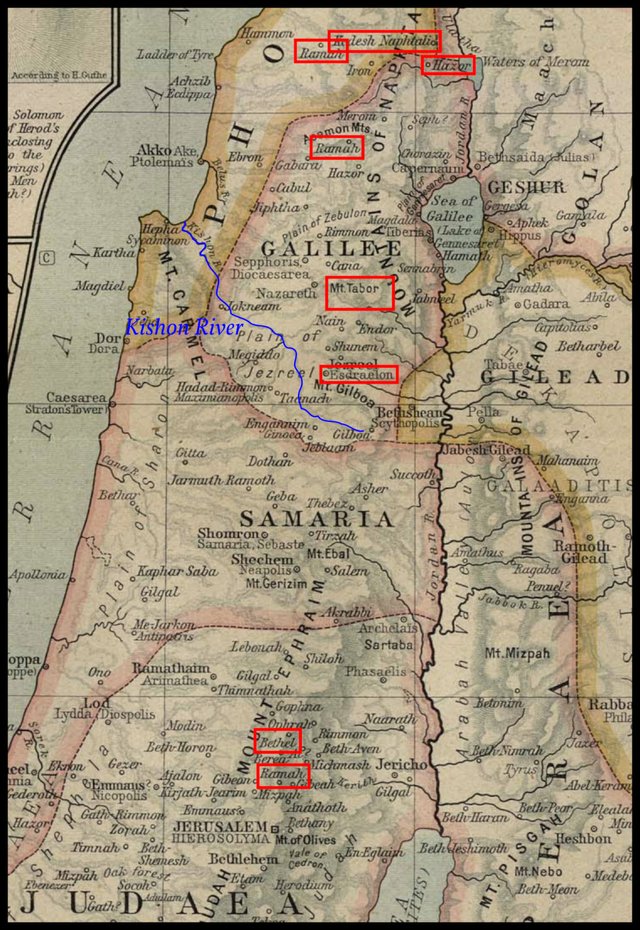

What of Deborah herself? The text associates her with Ramah and Bethel, in Mount of Ephraim, close to Jerusalem. But all the action takes place much farther north, in the vicinity of the Sea of Galilee (Lake of Sarsenet). Has the author or redactor confused two northern towns called Ramah and Bethel with a pair of better-known towns in Judaea?

We are told that Deborah delivered her judgements from beneath “the palm tree of Deborah.” But this appears to have resulted from the conflation of two different people:

Deborah Rebekah’s nurse, who accompanied Jacob, and died on the road to Beth-el. She was buried under a terebinth (“oak” in A.V. and R.V.), on this account named “Allon-bakut” (terebinth of weeping; Gen.xxxv. 8). This tree appears later on in Jewish history in connection with another Deborah. In Judges iv. 5 it is called “the palm-tree of Deborah,” as though named in honor of the prophetess, who sat under it and judged Israel; but it is more likely that “Deborah” in this connection is a reminiscence of the nurse. (Singer 4:489)

Perhaps both stories are aetiological myths, devised to account for the traditional name of an oracular shrine, the true origin of which had been lost to time. Was Deborah the deity associated with an ancient oracle known as The Palm? Or was she the priestess who spoke for the deity, like the Pythia who pronounced the words of Apollo at the Oracle of Delphi in Greece (Grant 295 ff)? An oracle is more likely to be named for its tutelary deity than for its priestess.

In Hebrew, Deborah means bee, which might be significant. Deborah is described as woman of Lapidoth. Is Lapidoth the name of her husband? In Hebrew, lapidoth means torches or lightning flashes. Is this related to Barak, which means lightning? Or is it a divine epithet, like Zeus of the Thunder-Bolt or Poseidon the Earthshaker?

Jabin King of Hazor shares his name with the leader of a Canaanite confederacy defeated by Joshua during the Conquest of Canaan (Joshua 11). Following his victory, Joshua burned Hazor to the ground.

Some scholars who are skeptical of the Joshuan Conquest of Canaan reject the account in Joshua 11 but accept that in Judges 4. Fundamentalists accept both accounts, concluding that there were two Kings of Hazor with the name Jabin. I am more inclined to accept the account in Joshua 11 than that in Judges 4. In an earlier article in this series—Joshua’s Northern Campaign—we saw that there was archaeological evidence for the burning of Hazor at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, which is where I locate Joshua’s Conquest. But there is also evidence that the city was burnt again towards the end of the Late Bronze Age, so perhaps there is also some truth to the account in Judges 4.

Significantly, Jabin is not mentioned in the Song of Deborah.

In Judges 4:11, Hobab is referred to as Moses’ father-in-law. In Numbers 10:29, Hobab is the son of Moses’ father-in-law Reuel (or Raguel). In Exodus 3:1, Moses’ father-in-law is called Jethro. Presumably, these discrepancies reflect independent traditions. Heber the Kenite is described as a descendant of Hobab.

The Talmudists, who tried to make sense of this plethora of names, came to the conclusion that Moses’ father-in-law had seven different names or titles: Reuel, Jether, Jethro, Hobab, Heber (Judges 4:11), Keni (Judges 1:16), and Putiel (Exodus 6:25) (Singer 7:173-174).

Jabin’s general Sisera is not known from any other early source. His identity, assuming he even existed, is unknown. The etymology of his name is unknown, though there is no lack of speculation: Philistine, Hittite, Hurrian, Egyptian, Sea Peoples. In The Legends of the Jews, he is described in fabulous terms:

The enemy whom God raised up against Israel was Jabin, the king of Hazor, who oppressed him sorely. But worse than the king himself was his general Sisera, one of the greatest heroes known to history. When he was thirty years old, he had conquered the whole world. At the sound of his voice the strongest of walls fell in a heap, and the wild animals in the woods were chained to the spot by fear. The proportions of his body were vast beyond description. If he took a bath in the river, and dived beneath the surface, enough fish were caught in his beard to feed a multitude, and it required no less than nine hundred horses to draw the chariot in which he rode. (Ginzberg 4:35)

Is it possible that Sisera is the same person as Shishak, the Egyptian conqueror who sacked Jerusalem during the reign of Rehoboam (I Kings 14:25-26)? In the Short Chronology, Shishak is identified with Thutmose III, who conquered the greatest empire in the history of ancient Egypt. In transcribing the Egyptian Thoth, the Hebrew scribes substituted the letter shin (-sh-) for the Egyptian -th- sound. In Herodotus, the same pharaoh is called Sesostris. There is certainly a similarity between Sesostris and Sisera.

Jael’s name is good Hebrew, meaning ibex, a type of wild mountain goat.

Sisera’s mother, whose grief is depicted in the Song of Deborah, is never named. In The Legends of the Jews she is called Themac, meaning “may she be destroyed.” The same name was borne by Cain’s wife (Ginzberg 4:38 and 6:198).

Song of Deborah

The Song of Deborah, which follows the victory over Sisera, has long been regarded as one of the oldest passages in the Bible:

The song belongs to the earlier poetry of the Hebrews, but shows such a remarkable power of expression and such a spontaneity that it takes a high place among the masterpieces of the world’s poetic literature. The Masoretic text, while exhibiting corruptions and obscurities, may be said on the whole to be fairly faithful to the original ... The poem may have been included in the “book of the wars of YHWH” (Num. xxi. 14; see Ber. 58a). Modern critics for the most part concede that the song was written very near the time at which the battle therein described took place. (Singer 4:490)

But is the Song as old as this? Today there is no longer a consensus on this point.

To be sure, the consensus outlined here is by no means perfect; several publications that appeared in the 1980s and 1990s diverge from it, sometimes in a major way. In particular, Alberto Soggin, Ulrike Schorn, and Barnabas Lindars see the Song, or at least the bulk thereof, as a product of the early monarchy; Ulrike Bechmann and Manfred Görg place it in the late pre-exilic period; Michael Waltisberg advocates early post-exilic provenance (fifth to third centuries BCE); and B.-J. Diebner shifts the composition’s date all the way to the turn of the eras ... With the text’s internal parameters and the external conditions of its existence considered in a systematic fashion, what we know as Judg. 5.2–31a presents itself as an integral part of the Deuteronomistic oeuvre and should be dated, accordingly, between c. 700 and c. 450 BCE. (Frolov 165 ... 183)

Frolov surmises that the Song of Deborah was actually composed by the Deuteronomist (Dtr), the supposed author of the Deuteronomistic History in late pre-Exilic, Exilic, or early post-Exilic times (Frolov 181):

As a very early text, predating Dtr by centuries, the Song would constitute arguably the strongest proof that word-for-word citation of received sources was a part of Dtr’s modus operandi. With this showcase piece turning out to be roughly contemporaneous with Dtr and broadly compatible with the Deuteronomic/Deuteronomistic worldview and agenda, chances increase that Joshua–Kings is a largely or even entirely authorial work whose creator was talented enough to feel at home in more than one genre and to be flexible in their deployment. (Frolov 184)

The numerous discrepancies between the Song and Chapter 4 suggest that they derive from independent traditions, but an alternative theory is that the prose account in Judges 4 was inspired by the Song:

Many scholars believe that the story was composed as an interpretation of the song. Stylistically, the song is in archaic Heb, and is extremely difficult, and in places, perhaps corrupt. It makes use of extensive contrasts and extreme transitions: from the Lord’s might to Israel’s unfortunate situation; from the Israelite tribes to their enemies; from Jael to Sisera’s mother. It also conveys an atmosphere of spontaneous enthusiasm. The poem does not mention Judah, Simeon, and Levi, suggesting that it was composed in the north. (Berlin & Brettler 519)

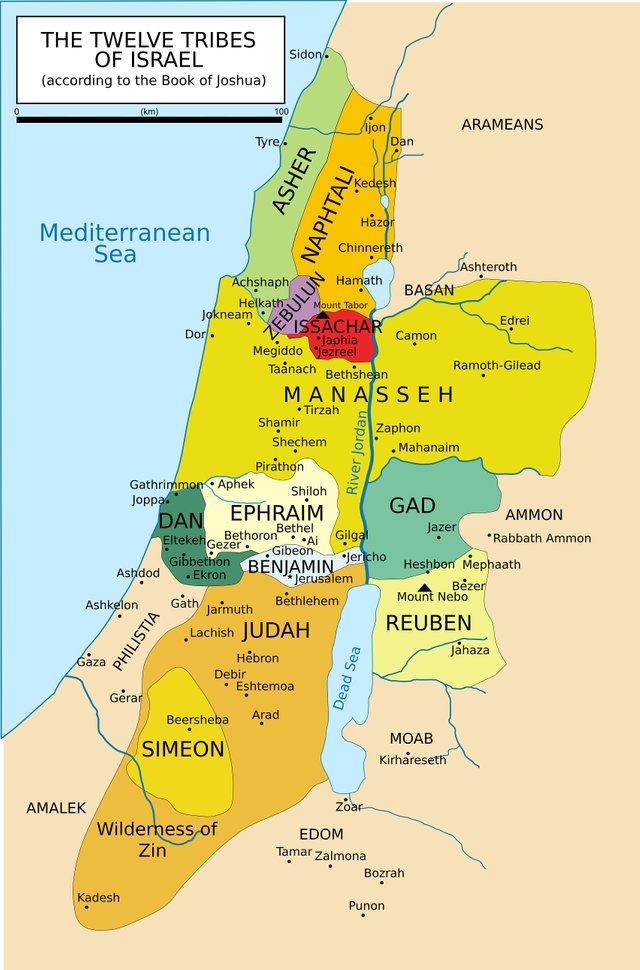

If Judges 4 was inspired by the Song, then it is easy to see how some elements could have been added to the tale—Jabin’s involvement, for example, or the inclusion of Mount Tabor—that were not in the Song. But Judges 4 also omits some elements that are in the Song. For example, only Zebulun and Naphtali fight against the Canaanites, whereas the Song also credits Ephraim, Benjamin, Machir (ie the western part of the Half-Tribe of Manasseh) and Issachar with the victory. The Song also mentions Reuben, Gilead (ie the eastern part of Manasseh), Dan and Asher, but implies that they declined to take part. On the other hand, some scholars believe that Judges 5:14-17, the four verses that mention these other tribes, are later interpolations (Na’amon 426).

The Song ends by contrasting the grief of Sisera’s mother with the glory of Jael, an image that is missing from the prose narrative.

Earlier Model

Some proponents of Martin Noth’s theory of the Deuteronomistic History have hypothesized that Judges 4-5 were modelled on the Passage of the Red Sea in Exodus 14-15:

In Jewish tradition this story, and the song which follows, constitute the haftarah for “Be-shallah,” whose Torah reading relates that the Lord confused the camp of Egypt (cf. Exod. 14.24; Judg. 4.15), that they drowned in the sea until “not one of them remained” (cf. Exod 14.28; Judg. 4.16), and that Moses and Israel sang a song to the Lord after they saw their salvation (cf. Exod. 15.1-18; Judg. ch 5). The prose account of the defeat of Sisera in ch 4, followed by the song in ch 5, is structurally similar to the prose account of the drowning of the Egyptians in Exod. ch 14, followed by the Song of the Sea in ch 15. (Berlin & Brettler 517)

Moses’ sister Miriam also participates in the celebrations, singing a shorter song of her own after Moses’ Song of the Sea. Is this why the song in Judges 5 is sung by Barak and Deborah?

Confused Geography

The account of Israel’s revolt against Jabin in Judges 4 is geographically detailed (Na’aman 427):

Jabin rules over the Israelites from Hazor.

His general Sisera is based in Harosheth of the Nations

Deborah holds court at the Palm of Deborah between Ramah and Bethel in the hill country of Ephraim.

Her general Barak is based in Kedesh Naphtali.

Barak marches with 10,000 troops of Naphtali and Zebulun to Mount Tabor.

Sisera consults Heber the Kenite at Zaanannim near Kedesh Naphtali, and learns from him that Barak is at Mount Tabor.

Sisera summons his army (900 iron chariots and a multitude of troops) from Harosheth of the Nations to the Kishon River.

Barak descends Mount Tabor and engages Sisera, routing his forces.

Barak pursues Sisera’s army and chariots to Harosheth of the Nations, where all the survivors of the battle are slain.

Sisera flees on foot to the tent of Jael, Heber’s wife—presumably at Zaanannim near Kedesh Naphtali, though this is not stated explicitly. Jael kills him as he sleeps.

Barak arrives at Jael’s tent in search of Sisera and is shown Sisera’s corpse.

Making sense of the sequence of events is complicated by the fact that some of these places are unknown. The identities of Harosheth, Zaanannim, Ramah and Bethel are still matters of scholarly debate. Nevertheless, Nadav Na’aman, Professor of Jewish History at Tel-Aviv University, believes that the geography of Judges 4 is confused and contradictory:

According to the prose, the Canaanite troops were summoned to Harosheth-ha-goiim ... crossed the Kishon river and fought the Israelites. After their defeat they fled back to their gathering place ... How, then, should we account for the fact that Sisera fled in an entirely different direction, namely, to the oak of Zaanannim ... a place located on Naphtali’s southern border (Josh. xix 33)? And how did it happen that Barak reached this northern place at the end of his pursuit, after he had followed the fleeing Canaanite troops westwards, to Harosheth-ha-goiim ...? (Na’aman 427-428)

And did Sisera advance southwards from the area of Hazor to the Kishon river to fight Barak who likewise went southwards from Kedesh of Naphtali to Mount Tabor ...? (Na’aman 428)

The oak of Zaanannim is situated near Kedesh according to the story ... However, Kedesh of Naphtali is located in the northern part of the tribal inheritance, whereas the oak of Zaanannim was a toponym on Naphtali’s southern border, near Adaminekeb and Jabneel (Josh. xix 33) ... (Na’aman 428-429)

Barak summoned Zebulun and Naphtali to Kedesh, his city. This is odd: Zebulun is situated in the area north of Wadi Kishon; his wandering northwards to Kedesh in order to return southwards to Mount Tabor, on the border of his inheritance, does not make geographical or military sense ... (Na’aman 429)

Deborah’s seat in the area of Bethel (v. 5) also involves geographical problems. According to the prose, only Zebulun and Naphtali participated in the battle against Sisera. Thus, in order to bridge the territorial gap between Deborah’s and Barak’s seats and to ensure her integration within the plot, the author (or redactor) made her walk all the way from the area of Bethel to Kedesh of Galilee, and then join Barak and his troops on their way southwards to Mount Tabor. The inhabitants of Mount Ephraim do not play any role in the prose account; Deborah’s wandering north and south is another odd trait in the story of Judg. iv. (Na’aman 429)

Na’aman draws a decisive conclusion from his analysis of the narrative:

The conclusion is inevitable: either the author of the story or a late redactor was not acquainted with the geography of northern Israel and mixed up the narrative elements in a way that excludes any geographical sense from the description. (Na’aman 429)

It would be easy, then, to dismiss the whole story as a late fiction, but Na’aman believes that a late Judean redactor who did not understand the story and had little knowledge of the topography of northern Israel was responsible for the geographical conundrums. Having isolated and removed this redactor’s supposed interpolations, Na’aman gives the following as the original account:

Jabin, “king of Canaan”, and his commander Sisera had subjugated the Israelite tribes. Deborah, the north Israelite prophetess, urged Barak to start a rebellion. He summoned the troops of Zebulun and Naphtali and they marched to Mount Tabor to fight the Canaanites. The Canaanites’ commander, Sisera, immediately called his army with its mighty iron chariots (compare Josh. xvii 16, 18; Judg. i 19) to Harosheth-ha-goiim, i.e., the western Jezreel plain, on the other side of the Kishon river. The fighting broke out near Wadi Kishon, and after his victory Barak chased the Canaanites up to their towns. Sisera fled alone on foot, and arrived at Jael’s tent, which must have been located in the western Jezreel plain. There he was betrayed and killed, just before the arrival of the Israelite commander at the place. The surrender of Jabin (v. 23), who subjugated the Israelites at the beginning of the story, closes the circle and brings the plot to its natural end. (Na’aman 432-433)

But even the original account, Na’aman believes, represents a departure from what actually happened:

B. Halpern has recently suggested that the story of Judg. iv was derived from the Song of Deborah ... In the discussion above it was pointed out that the story in its final form cannot be reconciled with the song, and that the description of the kings of Canaan who assembled “at Taanach by the Waters of Megiddo” to fight the Israelites across Wadi Kishon is in marked contrasts to the geographical background of the prose. The mention of the ten tribes in the song (Judg. v. 14-17) is another serious obstacle for the comparison of the two sources.

By eliminating both the interpolated ten tribes from the song (see n. 12 above) and the “Galilean oriented” redaction from the prose, the way is open for a fresh equation of the two sources. It seems to me that Halpern’s thesis is essentially correct and that the song was the source from which the author of the prose drew the main details for his story ...

By composing the “framework” ... and by eliminating the episodes of Meroz and the mother of Sisera, the narrator succeeded in crystallizing the plot. Two combating warriors and two women of contrasting characters are represented at the centre of the stage. The “king of Canaan” was added to the plot as the subjugating enemy, in accord with the “framework” of the stories of the Judges. It is clear that the author has in mind the kingdoms of his time, in which the king was the central figure and the chief commander sometimes led the army to battle ... In place of the kings of Canaan and their leader (Sisera) he therefore described a king and his commander of staff. The author further replaced certain geographical names by others, which presumably were better known to his readers. Thus, Mount Tabor took the place of Sarid and Harosheth-ha-goiim replaced the poetic “Taanach by the Waters of Megiddo”. (Na’aman 433-434)

Conclusion

The memory of a great battle between Zebulun-Issachar and a Canaanite army in the Plain of Jezreel may lie behind the story of Deborah, Barak, Sisera and Jael in Judges 4-5. But the chronology of this event is impossible to determine and its neat placement in the sequence of the Judges of Israel between the Conquest of Canaan by Joshua and the establishment of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah is probably spurious. Deborah’s association with an oracle in Ephraim suggests that she may have been a Canaanite deity.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), The Jewish Study Bible, Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Serge Frolov, How Old Is the Song of Deborah?, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, Volume 36, Issue 2, Pages 163-184, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA (2011)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 4, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1913)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 6, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1928)

- Elihu Grant, Deborah’s Oracle, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Volume 36, Number 4, Pages 295-301, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1920)

- Tyler Mayfield, The Accounts of Deborah (Judges 4-5) in Recent Research, Currents in Biblical Research, Volume 7, Number 3, Pages 306-335, SAGE Publishing, Thousand Oaks, CA (2009)

- Nadav Na’aman, Literary and Topographical Notes on the Battle of Kishon (Judges IV-V), Vetus Testamentum, Volume 40, Fascicle 4, Pages 423-436, Brill Publishers, Leiden (1990)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 4, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1903)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 7, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1904)

Image Credits

- Deborah: Guillaume Rouillé, Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum, Part 1, Page 34, Lyon (1553), Public Domain

- The Defeat of Sisera: Luca Giordano (artist), Museo del Prado, Madrid, Public Domain

- Jael and Sisera: James Northcote (artist), Royal Academy of Arts, London, Public Domain

- Victory of the Israelites and the Song of Deborah: Luca Giordano (artist), Museo del Prado, Madrid, Public Domain

- Tel Hazor (Tel el-Qedah): אסף.צ (photographer), Public Domain

- The Mother of Sisera Looked out a Window: Albert Joseph Moore (artist), Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery, Carlisle, Public Domain

- Martin Noth, Author of the Deuteronomistic Hypothesis: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Mount Tabor: © BiblePlaces.com, Fair Use

- The Song of Miriam: Luca Giordano (artist), Museo del Prado, Madrid, Public Domain

- The Geography of Judges 4: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, William Robert Shepherd, The Historical Atlas, Third Edition, Pages 6-7, Reference Map of Ancient Palestine, Henry Holt & Co, New York (1923), University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin, Public Domain

- The Twelve Tribes of Israel: © Janz, Creative Commons License

- The Plain of Esdraelon (Jezreel Valley) and Mount Tabor: © Joe Freeman (photographer), Creative Commons License