In the Book of Judges Samson is the twelfth and final Judge of Israel, but he was not the last Judge of Israel if the Old Testament is to be believed. In the following book of the Hebrew Bible, the Book of Samuel, which was later divided by the translators of the Septuagint into two books, we read:

Now Eli was ninety and eight years old; and his eyes were dim, that he could not see ... and he died: for he was an old man, and heavy. And he had judged Israel forty years. (I Samuel 4:15 ... 18)

Who was this man Eli? Was he a historical figure?

Biography

Eli’s history is bound up with that of Samuel, whom he prepares to be his successor:

After Samuel had been weaned, his parents brought him to the tabernacle at Shiloh to begin service as a lifelong Nazirite under Eli. The contrast between Eli’s young charge and his own two [reprobate] sons [Hophni and Phinehas] could scarcely be more stark ... Eli rebuked his sons for their wicked behavior, but they refused to listen to him.

An unnamed prophet—later identified by rabbinic sources as Samuel’s father Elkanah (Ginzberg 4:61, 6:222)—came to Eli and told him that the sins of his sons would bring judgment and that his priestly line would be cut off and superseded by that of another ...

After a severe military defeat suffered by the Israelites at the hands of the Philistines, Hophni and Phinehas accompanied the ark of the covenant onto the battlefield ... the Philistines fought bravely and captured the ark. Apparently Eli’s two sons were among the casualties who died in the battle ...

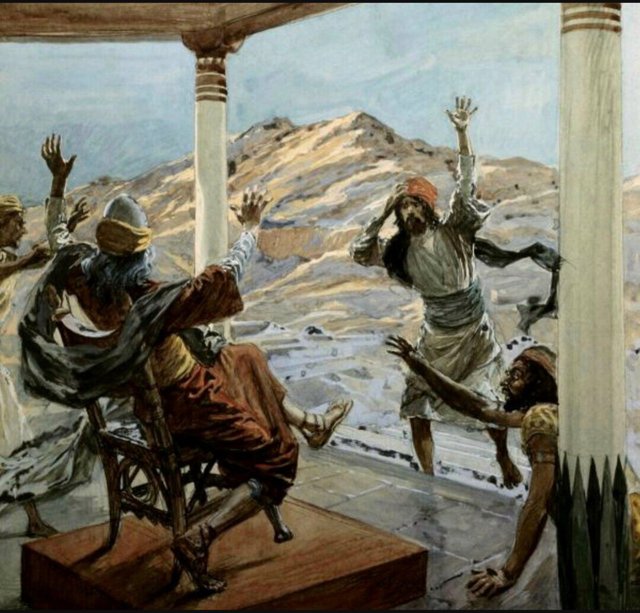

By this time Eli was an obese old man, ninety-eight years of age and nearly blind. When he heard the report of the death of his sons and the capture of the ark, the shock was such that he fell backward off his chair, broke his neck and died. He had been a judge in Israel for forty years. A tragic figure, Eli had successfully prepared Samuel for divine service but had failed with his own sons. (Freedman 351)

Eli is only referred to as a Judge of Israel in a single verse (I Samuel 4:18). Not everyone agrees that this refers to the office of the same name described in the Book of Judges:

Eli was not a tribal judge but a Levitical priest at the (post)tabernacle sanctuary at Shiloh. (Kitchen 208)

Eli is also described as High Priest at Shiloh, where the Ark of the Covenant was kept after the Conquest of Canaan.

For the first time in Israel, Eli combined in his own person the functions of high priest and judge, judging Israel for 40 years ... (Orr 928)

In the Greek Septuagint translation, he is said to have judged Israel for 20 years. Biblical scholars have been at pains to resolve this discrepancy:

He is said to have judged Israel 40 years (1 Sam. iv, 18) : the Septuagint makes it 20. It has been suggested, in explanation of the discrepancy, that he was sole judge for 20 years, after having been co-judge with Samson for 20 years (Judg. xvi, 31). (McClintock & Strong 137)

There are also discrepancies among the early sources concerning Eli’s age. In the Septuagint he was 90 when he died, and in the Syriac Version he was only 78 (Ellicott 310).

According to rabbinical sources, Eli was also President of the Sanhedrin, the supreme court in the land:

Eli succeeded to the three highest offices in the land: he was made high priest,. president of the Sanhedrin, and ruler over the political affairs of Israel. (Ginzberg 4:61)

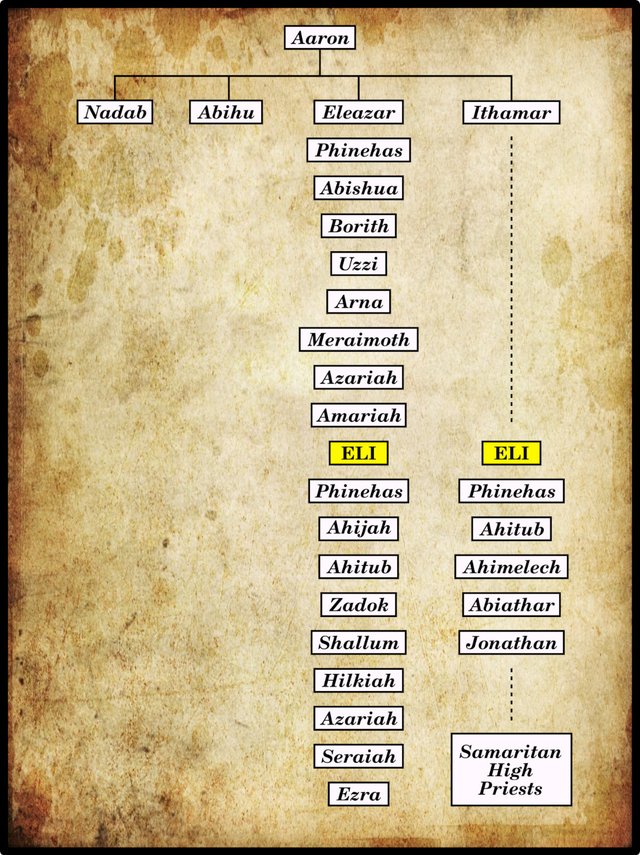

Genealogy

Eli’s ancestry has been traced back to Moses’ brother Aaron. His genealogy is never given explicitly in the Bible, but must instead be deduced from statements concerning his sons and their descendants. To confuse matters, the Scriptures contain two separate lineages for Eli:

Eli’s ancestry is not clearly outlined in the OT text, and any reconstruction must remain speculative. If the Ahimelech who was Eli’s great-grandson and successor (1 Sam 22:9, 11, 20; 14:3) is the same as the one mentioned in 1 Chr 24:3, then Eli was a descendant of Aaron’s son Ithamar (see also Josephus Ant 5.11.5 §361; contrast, however, 2 Esdras 1:2, where Eli is traced back to Eleazar, another of Aaron’s sons). 1 Sam 22:9-20 indicates that Eli’s descendants, through Ahimelech’s son Abiathar, continued to serve as priests at Nob, at least temporarily. When Doeg the Edomite slaughtered the priests at the command of Saul, Abiathar escaped (22:20) and shared the priesthood with Zadok under David (2 Sam 19:11). The prophecy concerning the demise of Eli’s line ... was further fulfilled when Solomon relieved Abiathar of his priestly duties (1 Kgs 2:26-27 ... ). The sole priesthood then reverted to the line of Eleazar under Zadok (cf. 1 Chr 6:4-8; Josephus Ant 5.11.5 §362), to whose house Ezra traced his own priestly lineage (Ezra 7:1-5). (Freedman 351)

It has been noted by Biblical scholars that the Judgeship of Eli, unlike those his predecessors, is never properly introduced:

Biblical criticism has advanced few new theories in regard to Eli’s life. The only point that has been made with some probability is mentioned by H. P. Smith (“Samuel,” in “International Critical Commentary,” p. 30): “An earlier source on Eli’s life contained originally some further account of Eli and of Shiloh, which the author [of the Books of Samuel] could not use. One indication of this is the fact that Eli steps upon the scene in i. 3 without introduction.” H. P. Smith also admits that great difficulties are encountered “in assigning a definite date to either of our documents.” (Singer 107)

Eli’s two sons have Egyptian names:

Eli’s two reprobate sons—unfortunately also priests of the Lord [I Samuel 1:3]—bore appropriately Egyptian names: Hophni (“Tadpole”) and Phinehas (“The Nubian”). (Freedman 350-351)

Phinehas is a name we have encountered before. The elder Phinehas was a grandson of Aaron and son of Eleazar. He was the third High Priest of Israel, after his grandfather and father. According to rabbinical sources, Eli succeeded this older Phinehas in the office of high priest:

In his office as high priest he was successor to no less a personage than Phinehas, who had lost his high-priestly dignity on account of his haughty bearing toward Jephthah. (Ginzberg 4:61)

It is impossible to square this tradition with the lineage given in II Esdras, according to which no less than seven generations separated Eli from Phinehas. The other lineage, however, does not tell us how many generations elapsed between Ithamar and Eli, so it is at least possible in this scenario that Eli succeeded Phinehas as High Priest. This chronology, however, implies that the rise of the monarchy, which was inaugurated when Samuel anointed Saul, took place shortly after the Exodus—not several centuries later, as the Scriptures claim.

Philistines

Eli’s Judgeship is marred by the loss of the Ark of the Covenant to the Philistines. The Philistines are the implacable enemies of Israel from the Judgeship of Samson until the rise of the so-called Neo-Assyrian Emperors during the Divided Monarchy.

Who were the Philistines? Where did they come from? To what period of history did they belong? These are questions that we will examine in a future article. The answers will surely have an important bearing on the true chronology of ancient Israel.

Eli and the Samaritans

According to the Samaritans, it was Eli who precipitated the schism between the Jews and the Samaritans, when he abandoned Mount Gerizim and established a rival shrine at Shiloh. The Ark of the Covenant that was kept at Shiloh was a replica of the true Ark.

The Samaritan historian Abu’l-Fath, who wrote a history the Samaritans in Arabic in the 14th century, describes the origin of the schism as follows:

A terrible civil war broke out between Eli son of Yafni, of the line of Ithamar, and the sons of Phineas, because Eli son of Yafni resolved to usurp the High Priesthood from the descendants of Phineas. He used to offer sacrifice on the altar of stones. He was 50 years old, endowed with wealth and in charge of the treasury of the children of Israel ...

He offered a sacrifice on the altar, but without salt, as if he were inattentive.

When the Great High Priest Ozzi learned of this, and found the sacrifice was not accepted, he thoroughly disowned him; it is (even) said that he rebuked him.

Thereupon he [Eli] and the group that sympathized with him rose in revolt and at once he and his followers and his beasts set off for Shiloh>

Thus Israel split into three factions ...At this time the children of Israel became three factions: A (loyal) faction on Mount Gerizim [Samaritans]; a heretical faction that followed false gods [Gentiles]; and the faction that followed Eli son of Yafni in Shiloh [Jews]. (Anderson & Giles 11-12 : Stenhouse 47-48)

This tradition, which follows the Ithamar lineage, identifies Eli’s father as Yafni, which is probably an Arabic form of Hophni. This is certainly plausible, as it would be appropriate for Eli to name his eldest son after his own father.

The orthodox Jewish position is that the Samaritans emerged following the Assyrian conquest of the Kingdom of Israel and the deportation of its people. The Samaritans were either the remnant Israelite population that escaped deportation or a foreign people who were settled in Israel by the Assyrians and who adopted the Jewish faith. Genetic studies suggest that modern Samaritans and Jews share a common ancestry.

Conclusion

Eli is principally remembered for his rôle in preparing Samuel for his ministry. The historicity of Samuel is, therefore, inextricably linked with that of Eli. There are, however, several anomalies in the account of Eli that cause me to doubt his historicity.

Like Jesus of Nazareth, Eli is given two contradictory genealogies, which casts doubt on the veracity of both.

The unlikely Egyptian names for Eli’s sons also calls his story into question. Were these names chosen because Hebrew names were considered unfitting for two reprobates?

The contradictory histories of Eli found in Judaism and Samaritanism also invite skepticism, though the genetic evidence, which favours the latter, inclines me to entertain the possibility that Eli was a historical personage after all—a schismatic, who lived shortly before the establishment of the Kingdom of Israel. His strange death—he falls backward off his seat and breaks his neck when he is told the bad news of the capture of the Ark and the death of his sons—is, perhaps, unnecessarily precise and detailed for a fictional account.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Robert T Anderson & Terry Giles, The Keepers: An Introduction to the History and Culture of the Samaritan, Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody, Massachusetts (2002)

- Charles John Ellicott (editor), An Old Testament Commentary for English Readers, Volume 2, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co, London (1883)

- David Freedman (editor-in-chief), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, Doubleday, New York (1992)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 4, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1913)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 6, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1928)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2003)

- John McClintock, James Strong, Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 3, Harper & Brothers, New York (1882)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 2, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 5, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1903)

- Henry Preserved Smith, The International Critical Commentary: A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Books of Samuel, T & T Clark, Edinburgh (1904)

- Paul Stenhouse, The Kitab al-Tarikh of Abu’l-Fath, Translated into English with Notes, Mandelbaum Trust, University of Sydney, Sydney (1985)

Image Credits

- Hannah Presenting Her Son Samuel to Eli: Jan Victors (artist), Berlin State Museums, Berlin, Public Domain

- Eli and Samuel: John Singleton Copley (artist), Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, Public Domain

- Shiloh: © Holy Land Site Ministries, Fair Use

- The Holy Ark Falling into the Hands of the Philistines: Gerrit Claesz Bleker (artist), Museum of Fine Arts, budapest, Public Domain

- Phinehas and Hophni: William de Brailes (artist), Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland, Public Domain

- The Death of Eli: Georges Bertin Scott (artist), after James Tissot (artist), The Bad News, The Jewish Museum, New York, Public Domain