The story of Gideon, Fifth Judge of Israel, is recounted in Judges 6-8. It is quite the epic:

For seven years the Midianites, Amalekites and Children of the East subjugate the Israelites, who have returned to their evil ways.

Gideon, the son of Joash of the Abiezrite Clan in the Tribe of Manasseh, is chosen by Yahweh to free Israel.

The Angel of Yahweh visits Gideon at his home in Ophrah and tells him that the Lord is with him.

Guided by the angel, Gideon throws down the altar of Baal.

Gideon requests proof of Yahweh’s will by having two miracles performed. Gideon places a fleece of wool upon the floor. Upon waking the following morning, he finds that the fleece is covered in dew while the surrounding ground is dry. The next morning, he awakes to find the opposite: the fleece is dry while the surrounding ground is covered in dew.

Gideon and his host encamp beside the Well of Harod. The Midianites camp to the north of them, by the Hill of Moreh, in the valley.

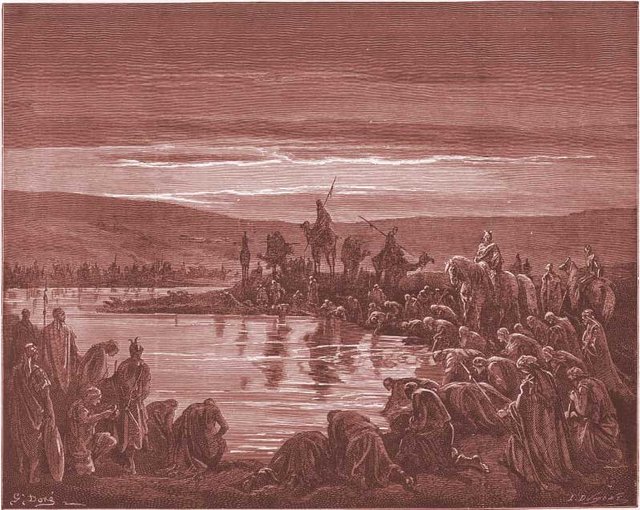

The Israelites are greatly outnumbered by 135,000 Midianites. Nevertheless, Gideon allows the fearful among his host to leave. 22,000 men depart, leaving Gideon with 10,000.

Yahweh tells Gideon that the Israelites are still too many. He instructs him to bring them to the water. All those who lap the water with their tongues, as a dog laps, are separated from those who kneel down to drink, putting their hands to their mouths. There are 300 of the former. Yahweh tells Gideon that he will deliver Israel with the 300. The rest depart to their homes.

The night before the battle, Gideon approaches the Midianite camp. There he overhears a Midianite man tell a friend of a dream in which a loaf of barley bread tumbled into the Midianite camp, causing their tents to collapse. This is interpreted as meaning that Yahweh has delivered Midian into the hands of Gideon.

Gideon returns to the Israelite camp and gives each of his men a trumpet (shofar) and a clay pitcher with a torch hidden inside.

Divided into three companies, Gideon and his 300 men march on the Midianite camp. They blow their trumpets, break their pitchers and hold up the lighted torches, crying out “The sword of the Lord and of Gideon”. The Midianite army, thinking that they are being attacked by a much larger host, flee in disarray.

The Midianites flee to Bethshittah in Zererath, and to the border of Abelmeholah, unto Tabbath.

Israelites from Naphtali, Asher and Manasseh pursue the Midianites.

Upon receiving instructions from Gideon, the Ephraimites muster and take the waters unto Bethbarah and Jordan.

The Ephraimites capture two Midianite princes: Oreb and Zeeb. Oreb is slain upon the rock Oreb, and Zeeb at the winepress of Zeeb. Their heads are brought to Gideon on the other side Jordan.

The Ephraimites are indignant to be called upon so late in the campaign, but Gideon assuages their anger by pointing out that their victory over Oreb and Zeeb in Ephraim is greater than his in Abiezer.

Gideon and his 300 cross the Jordan in pursuit of the Midianite kings Zebah and Zalmunna.

The men of Succoth and Peniel refuse to provision Gideon and his men.

Zebah and Zalmunna make camp in Karkor with about 15,000 men—all that is left of the Children of the East.

Gideon approaches the Midianites by the way of them that dwell in tents on the east of Nobah and Jogbehah. He routs the Midianites.

Zebah and Zalmunna flee, but Gideon gives pursuit and captures them.

Gideon punishes Succoth and Peniel, pulling down the Tower of Peniel.

Gideon asks Zebah and Zalmunna: “What manner of men were they whom ye slew at Tabor?” They reply: “As thou art, so were they; each one resembled the children of a king.” Gideon says: “They were my brethren, even the sons of my mother: as the Lord liveth, if ye had saved them alive, I would not slay you.”

Gideon commands his firstborn son Jether to slay Zebah and Zalmunna, but Jether, being young, is afraid to comply. So Zebah and Zalmunna call upon Gideon to do the deed, which he does.

The Israelites call upon Gideon to become their king and establish a dynasty, but he refuses.

Gideon fashions an ephod—a sacred apron?—from 1700 shekels of gold looted from the Midianites (“For they had golden earrings, because they were Ishmaelites”), and places it in Ophrah. Eventually, however, it comes to be worshipped as an idol, causing Israel to turn away from Yahweh once again.

Gideon has 70 sons by many different wives. His Shechemite concubine bears him a son, Abimelech.

Gideon dies in his old age, and is buried in the sepulchre of Joash his father, in Ophrah of the Abiezrites.

As soon as Gideon is dead, the Israelites backslide and worship Baalim, making Baalberith their false god. Gideon and his family are forgotten.

A story rich in detail. But how much of it is true?

Jerubbaal or Gideon

At four places in Judges 6-8 Gideon is given the name Jerubbaal:

6:32—Therefore on that day he called him Jerubbaal, saying, Let Baal plead against him, because he hath thrown down his altar.

7:1—Then Jerubbaal, who is Gideon, and all the people that were with him, rose up early, and pitched beside the well of Harod: so that the host of the Midianites were on the north side of them, by the hill of Moreh, in the valley.

8:29—And Jerubbaal the son of Joash went and dwelt in his own house.

8:35—Neither shewed they kindness to the house of Jerubbaal, namely, Gideon, according to all the goodness which he had shewed unto Israel.

Judges 6:32 explains how Gideon acquired this name, but this etymology is rejected by modern scholars:

Jerubbaal, originally a theophoric name, praising Baal as founder. The component “Jeru,” repeated in the name “Jerusalem,” means to establish. The derivation of the name here as Let Baal Contend ... is a folk etymology. (Berlin & Brettler 525)

In other words, Jerubbaal is a pagan name, quite unfitted for a Judge of Israel. The presence of two different names suggests that the story of Gideon is a conflation of two independent tales. Numerous other repetitions have led scholars to infer the existence of three, or even four, principal sources:

The critical school declares the story of Gideon to be a composite narrative, mainly drawn from three sources: the Jahvist (J), the Elohist (E), and the Deuteronomic (D) writers. In the portion credited to E there is recognized by the critics an additional stratum, which they denominate “ E2”. Besides, later interpolations and editorial comments have been pointed out. Behind these various elements, and molded according to different viewpoints and intentions, lie popular traditions concerning historical facts and explanations of names once of an altogether different value, but now adapted to a later religious consciousness ... While it is exceedingly difficult to separate in all particulars the various components of the three main sources, the composite nature of the Gideon narrative is apparent not so much, as has been claimed by some, from the use of the two names “Gideon” (an appellative meaning “hewer”) and “Jerubbaal” as from the remarkable repetitions in the narrative. (Singer 662)

Israel Finkelstein and Oded Lipschits also distinguish four independent narrators:

We can summarize this section [Judges 6-8] as follows:

The old story: 6:2aα (... without »Israel«), 11aβ–b (basic details in the Deuteronomistic verse); 34aβ–b–35a; 7:1 ... 5a, 6, 8aβ–b, 11b, 13–14a (without »the man of Israel«), 15aα ... 16a–bα, 17–18bα (without the references to the torches), 19, 21a, 22aα, 22b; 8:4, 5bβ, 10aα, 11a–bα, 12aα, 12bα, 18a (without Tabor), 19–20 (without »as the LORD lives«), 21bα, 28aα.

The author of the Book of Saviors: 6:2b, 6a; 7:14b, 15aβ, 28a; 8:5–9, 13–17 (these verses might also be part of the Deuteronomistic level, and this is why we mention some of them also below.

The Deuteronomistic layer: 6:1, 6b, 11aα, 12, 14aβ–bα, 15–19aα, 19b, 20a–bα, 21–24, 33, 34aα, 35b; 7:2–4, 5b, 7–8aα, 9–11a, 14aβ–b, 15b ... 61bβ, 18b, 20, 21b, 22aβ; 8:5–9, 13–17, 28aβ-b, 32–34.

Post-Deuteronomistic additions: 6:3–5, 7–10, 13–14aα, 14bβ, 19aβ, 20bβ, 25–32, 36–40; 7:2–8a, 12, 23–25; 8:1–3, 10aβ–b, 11bβ, 12aβ, 12bβ, 18b, 21a, 21bβ, 22–27, 29–31, 35. (Finkelstein & Lipschits 10)

The repetitive nature of the story has resulted in numerous inconsistencies.

In Judges 6:8 Yahweh sends the Israelites a prophet. In 6:11, his messenger is called the Angel of Yahweh. But in 6:14, when Gideon addresses the Angel, it is the Lord himself who replies.

There are also two different accounts of how Gideon’s doubts are assuaged. In 6:20, when he prepares meat and unleavened bread for the Angel, the Angel touches the food with the tip of his staff and fire flares from the rock, consuming the offering. This convinces Gideon that he has seen the Angel of the Lord face to face. But later, in 6:36-40, Gideon refuses to believe until the Lord has worked the two miracles of the fleece. Even here, the second miracle may be a doublet of the first.

There are two pairs of Midianite leaders: the generals Oreb & Zeeb, and the kings Zebah and Zalmunna.

Two towns, Succoth and Penuel, refuse to provision Gideon and his men and are subsequently punished for their failure to lend assistance.

In Judges 8:24, the Midianites are parenthetically described as Ishmaelites, a different people. Both were traditionally descended from sons borne to Abraham by concubines: Midian son of Keturah, and Ishmael son of Hagar.

In II Samuel 11:21, Gideon is called Jerubbesheth:

“Jerubbaal” is a theophorous name in which “Baal” originally and without scruples was the synonym of “YHWH,” its meaning being “Ba’al contends” or “Ba’al founds” ... The story (Judges vi. 29-32) belongs to a numerous class of similar “historical” explanations of names expressive of a former religious view, either naively provoked by the no longer intelligible designation, or purposely framed to give the old name a bearing which would not be offensive to the later and more rigorous development of the religion of YHWH, a purpose clearly apparent in the change of such names as “Ishbaal” and “Jerubbaal” into “Ishbosheth” and “Jerubbesheth” (II Sam. xi. 21). (Singer 662)

None of this lends any credence to the story of Gideon.

Oracle

When the Angel of Yahweh first visits Gideon, Gideon is seated under a sacred oak tree in Ophrah. This is reminiscent of the story of Deborah, who delivers her judgements from beneath the holy Palm of Deborah in Ephraim (Judges 4:5). In the last article, I hypothesized that Deborah was originally a pagan deity associated with a Canaanite oracle in Ephraim. Could Gideon, likewise, be a pagan god associated with a similar arboreal oracle in Manasseh?

When Gideon is called by the Lord, he not only throws down the altar of Baal that his father has built: he also cuts down the Asherah pole, or tree sacred to the Canaanite mother goddess Asherah. Presumably, this is the same as the sacred oak tree beneath which Gideon is seated when the Angel first visits him.

After his victory, Gideon fashions an ephod out of 1700 shekels of gold looted from the Midianites and sets it up in Ophrah. In later times, the ephod was an apron worn by Jewish priests. But was Gideon’s ephod an item of clothing or an idol?

Gesenius and others (Thes. p. 135 ; Bertheau, p. 133 iq.) follow the Peshite in making the word ephod here mean an idol, chiefly on account of the vast amount of gold (1700 shekels) and other rich material appropriated to it. But it is simpler to understand it as a significant symbol of an unauthorized worship. (McClintock & Strong 856)

It is impossible to overlook these traces of pre-Judaic paganism. Their inclusion suggests to me that any historical elements in this story belong to a period of history before the Joshuan Conquest of Canaan.

Transjordan

Initially, Gideon’s campaign against the Midianites is located in northern Canaan, in the territory of Issachar (southwest of the Sea of Galilee). But his pursuit of the Midianite kings, Zebah and Zalmunna, takes him across the River Jordan into Gad and Ammon, far to the south. This change of theatre suggests that we are dealing with two separate engagements, which were later conflated into a single narrative.

This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the two kings are only mentioned for the first time after the Midianite host has been routed. And when Gideon finally captures them, he converses with them about events that have not yet been recounted. He asks them about the men they slew at Mount Tabor, a location that was not mentioned during the campaign in Issachar. It transpires that these were Gideon’s brothers (or half-brothers), and Gideon executes the two kings in retaliation for this act.

The first two places Gideon comes too after he crosses the Jordan in pursuit of Zebah and Zalmunna are called Succoth and Peniel. A passage in the Jerusalem Talmud identifies Sukkot with a settlement also known as Dar’ellah. Based on this, Succoth has been identified with Deir Alla, a Jordanian town about 40 km northwest of Amman. An archaeological tell on the site has been excavated. The most notable find is an inscription that refers to Balaam, the Moabite prophet whose story was recounted in Numbers 22-24.

Peniel is now identified with one of two peaks overlooking the River Jabbok (Zarqa River), the other peak being identified with Mahanaim. Peniel is thought to be the eastern peak, Tall adh-Dhahab ash-Sharqi, and Mahanaim the western peak, Tall adh-Dhahab al-Gharbi. These peaks are about 8 km to the east of Deir Alla.

Gideon overtakes Zebah and Zalmunna at a place called Karkor, which he approaches by the way of them that dwelt in tents [ie Bedouin] on the east of Nobah and Jogbehah.

According to Numbers 32:42, Nobah of Manasseh captured the village of Kenath in Transjordan during Moses’ conquest of that region and renamed it Nobah. Nobah is identified with the modern town of Qanawat in the south of Syria. If this is true, then the original name of Kenath must have survived. I Chronicles 2:23 refers to the same town as Kenath. But Qanawat lies almost 100 km to the east of the Sea of Galilee, which is surely too far for Gideon to have pursued the Midianites. It is also nowhere near the places identified with Succoth and Peniel.

Jogbehah has been identified with Rujm el-Jebeha, a district in the northwest of Amman, in Jordan. The ruins of an Ammonite fortress are still extant here.

Clearly, if we accept all of these identifications, we cannot make sense of Judges 8. Qanawat lies about 100 km northeast of Peniel, while Rujm el-Jebeha lies 25 km southwest of Peniel. Wherever Karkor lay, Gideon cannot have passed through both Qanawat and Rujm el-Jebeha to reach it. The geography would make much more sense if Nobah could be located somewhere between Peniel and Rujm el-Jebeha, and Karkor somewhere to the east or southeast of Amman (Rabbah).

Karkor, however, remains a mystery. Several candidates have been proposed—Qarqar, el-Kerah, Kerak—but none of them fits the geography. Qarqar, a city mentioned in the Annals of Shalmaneser III, lay in northwestern Syria, over 400 km from Amman. El-Kerah lay to the south of Edrei, which is 75 km north of Amman. Kerak lay in Moab, 90 km south of Amman. Finkelstein & Lipschits suggest that the Biblical Karkor is a corruption of Aroer, overlooking Amman (Finkelstein 16). This Aroer is mentioned in Joshua 13:25 as lying before Rabbah (ie Amman), but its identity is still unknown. There is a slight similarity in the Hebrew spelling of these two toponyms: ערוער (Aroer) and קרקר (Karkor).

Archaeology

In 2019, archaeologists excavating a site in southern Canaan, close to the ruins of the ancient city of Lachish, found a potsherd inscribed with the name Jerubbaal in Proto-Canaanite (Early Alphabetic). The site where the find was made, Khirbet al-Ra‛i, is an ancient Cannanite-Philistine settlement tentatively identified by some scholars with the Biblical Ziklag:

It was unearthed in 2019 at Khirbet al-Ra‘i, located 4 km west of Tel Lachish, in a level dated to the late twelfth or early eleventh century BCE. Only part of the inscription had survived, with five letters indicating the personal name Yrb‘l ( Jerubba‘al). This name also appears in the biblical tradition, more or less in the same era: “[Gideon] from that day was called Yrb‘l” ( Judg. 6:31–32). (Rollston 1)

Rollston’s dating is, of course, in line with the Conventional Chronology of the Iron Age in Palestine:

In the 2019 season, we opened a small probe in the south-eastern side of Area A and identified an earlier occupation phase. Judging by the pottery assemblage, this phase too is of the Iron Age I, and hence should date from the late twelfth or first half of the eleventh century BCE. Part of stone-lined Silo A310 was revealed in the south-eastern corner of the probe, and all the sediment inside was sifted. On the last day of the season two small pottery sherds bearing letters were discovered. (Rolleston 3)

In the Short Chronology, to which I subscribe, the Joshuan Conquest of Canaan took place at the end of the Middle Bronze Age and the beginning of the Late Bronze Age, around 760 BCE. The Iron Age I must, therefore, be assigned to the time of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. But even if we accept the conventional dating of Rollston’s inscription, his find does not prove that Jerubbaal was a historical character, or that the inscription has anything to do with the Biblical Jerubbaal. Rollston’s reading has even been questioned. Another epigrapher, Haggai Misgav of Hebrew University, has suggested the alternative reading of Azruba‛al (Borschel-Dan).

The Khirbet al-Ra‘i inscription is an intriguing find, and proves that this name—or something like it—was current some centuries before the Book of Judges was compiled. It is not known when Judges reached its final form, but some time during the Babylonian Exile is the favoured date. In the Conventional Chronology, this would be around 550 BCE. In the Short Chronology, it would be more like 340 BCE, if not later.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), The Jewish Study Bible, Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Amanda Borschel-Dan, Five-Letter Inscription Inked 3,100 Years Ago May Be Name of Biblical Judge, The Times of Israel, 12 July 2021, Jerusalem (2021)

- Israel Finkelstein & Oded Lipschits, Geographical and Historical Observations on the Old North Israelite Gideon Tale in Judges, Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft, Volume 129, Issue 1, Pages 1-18, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin (2017)

- Livia Gershon, This 3,100-Year-Old Inscription May Be Linked to a Biblical Judge, Smithsonian Magazine, 13 July 2021, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (2021)

- John McClintock & James Strong, Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 3, Harper & Brothers, New York (1894)

- Christopher Rollston, The Jerubba‘al Inscription from Khirbet al-Ra‘i: A Proto-Canaanite (Early Alphabetic) Inscription, Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology, Volume 20, Number 2, Pages 1-15, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem (2021)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 5, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1904)

Image Credits

- Gideon: Guillaume Rouillé, Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum, Part 1, Page 35, Lyon (1553), Public Domain

- Gideon Choosing His Soldiers: Gustave Doré (engraver), La Grande Bible de Tours, Public Domain

- Gideon’s Campaign: © A History of Israel, Fair Use

- Gideon’s Battles: © Bible Study, Fair Use

- Gideon Overcoming the Midianites: Peter Paul Rubens (artist), North Carolina Musuem of Art, Raleigh, Public Domain

- The Well of Harod: © Aaadir (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Fara’ata, Palestine (Ophrah?): © Khaled Ishtawi (photographer), Fair Use

- The Hill of Moreh: Almog (photographer), Public Domain

- Asherah: Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv, Ashtoret Anat (photographer), Public Domain

- Tanit: Reuben and Edith Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, © Hanay (photographer), Creative Commons License

- The Valley of Jezreel and Mount Tabor: © Joe Freeman (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Tall adh-Dhahab ash-Sharqi (Peniel?): © יעקב (Jacob) (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Map of Gideon’s Campaign: © Crossway, Fair Use

- Rujm Al-Malfouf (An Ammonite Watchtower in Amman): © Bashar Tabbah (photographer), Creative Commons License

- The Jerubbaal Potsherd: © Dafna Gazit (photographer), Israel Antiquities Authority, Fair Use