Jephthah, the Eighth Judge of Israel, is one of the Bible’s most memorable characters, and his story, which is recounted in Judges 11:1-12:7, one of the Bible’s most popular narratives. His period in office was only six years, but he is regarded as a major judge on account of the number of Bible verses assigned to him—forty-seven. Like his predecessor, Jair, he was a Gileadite from Transjordan. He was, however, of illegitimate birth:

Now Jephthah the Gileadite was a mighty man of valour, and he was the son of an harlot: and Gilead begat Jephthah. And Gilead’s wife bare him sons; and his wife’s sons grew up, and they thrust out Jephthah, and said unto him, Thou shalt not inherit in our father’s house; for thou art the son of a strange woman. Then Jephthah fled from his brethren, and dwelt in the land of Tob: and there were gathered vain men to Jephthah, and went out with him. (Judges 11:1-3)

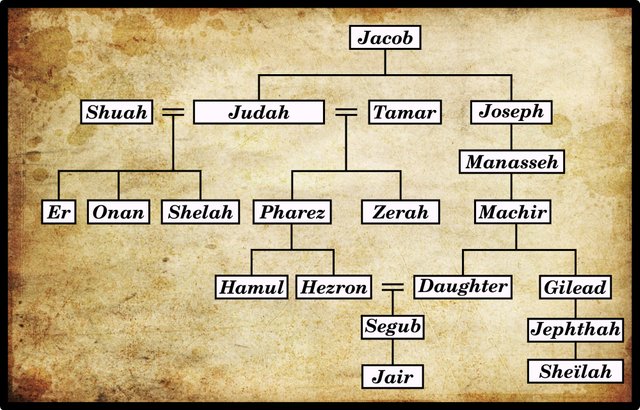

The identity of Jephthah’s father Gilead is disputed, but some commentators identify him with the grandson of Manasseh (Ellicott 230).

Tob is commonly identified with Aṭ-Ṭaībah (or Taibah), a town in Gilead, about 21 km SSE of the southern point of the Sea of Galilee.

The Hebrew expression אֲנָשִׁ֣ים רֵיקִ֔ים [anashím rêqîm] is variously translated as a gang of scoundrels, a group of rebels, worthless fellows, worthless and unprincipled men, etc. In Strong’s Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, Number 7386 רֵק [rêq] is translated as empty, worthless (Strong 108).

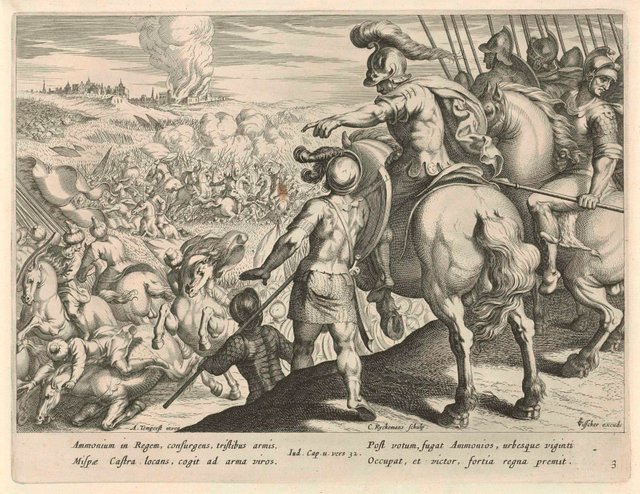

The Ammonites, a Canaanite people who also dwelt in Transjordan, make war on Israel and Jephthah is recalled from exile to lead the Israelite forces in the field. This account of Jephthah echoes that of Abimelech, who was born to Gideon not by one of his wives but by a concubine, and who succeeded in persuading the Gideonites to accept him as their leader:

This story depicts Jephthah similarly to Abimelech, hinting at his problematic rule. (Berlin & Brettler 535)

After his installation as leader, Jephthah opens negotiations with the King of the Ammonites. He is unnamed in the Bible, but Pseudo-Philo identifies him as Getal (Ginzberg 4:43). The Ammonites lay claim to all the land between the Arnon, the Jabbok and the Jordan.

In Numbers and Deuteronomy, the territory which the Ammonites claim comprises most of the Kingdom of Sihon the Amorite. Jephthah argues that this territory was conquered by Israel from the Amorites, not from the Ammonites, whose territory they never violated:

And Israel smote [Sihon the Amorite] with the edge of the sword, and possessed his land from Arnon unto Jabbok, even unto the children of Ammon: for the border of the children of Ammon was strong. (Numbers 21:24)

This argument, however, is undermined by a passage in Joshua:

And Moses gave inheritance unto the tribe of Gad, even unto the children of Gad according to their families. And their coast was Jazer, and all the cities of Gilead, and half the land of the children of Ammon, unto Aroer that is before Rabbah. (Joshua 13:24-25)

Note, in passing, the summary of the Exodus:

But when Israel came up from Egypt, and walked through the wilderness unto the Red sea, and came to Kadesh; (Judges 11:16)

The order of events is at odds with the earlier account of these events, in which the Israelites cross the Yam Suph (here translated as Red Sea) before they traverse the wilderness to Kadesh:

The account of the diplomacy used by J[ephthah] to prevent the Ammonites from invading Gilead is possibly an interpolation, and is thought by many interpreters to be a compilation from Nu[mbers] 20-21. It is of great interest, however, not only because of the fairness of the argument used (11:12-28), but also by virtue of the fact that it contains a history of the journey of the Israelites from Lower Egypt to the banks of the Jordan. This history is distinguished from that of the Pent[ateuch] chiefly by the things omitted. (Orr 1587)

Jephthah tells the Ammonites to be satisfied with the land their god gave to them, just as the Israelites are satisfied with what Yahweh gave to them:

Wilt not thou possess that which Chemosh thy god giveth thee to possess? So whomsoever the Lord our God shall drive out from before us, them will we possess. (Judges 11:24)

But Chemosh is associated with the Moabites. The principal god of the Ammonites was Milcom:

For a variety of reasons, including the fact that Chemosh (v. 24) is the national god of Moab, not Ammon, and that the story mentions the Moabite King Balak (v. 25), many scholars believe that much of this [chapter] was a separate document concerning Israel and Moab; once this became integrated here, Moab was changed to Ammon-at the beginning and at the end (vv. 12-14, 27-28) (Berlin & Brettler 536)

Finally, Jephthah reminds the Ammonites that they have had plenty of time to lay claim to this land since it was settled by the Israelites:

While Israel dwelt in Heshbon and her towns, and in Aroer and her towns, and in all the cities that be along by the coasts of Arnon, three hundred years? why therefore did ye not recover them within that time? (Judges 11:26)

This chronology is consistent with the earlier books of the Old Testament. According to the Seder Olam Rabbah, the Kingdom of Sihon was conquered by the Israelites just before the death of Moses, which took place in the year 2487, while Jephthah’s Judgeship began 293 years later, in the year 2779 (Johnson).

With war inevitable, Jephthah makes a fateful vow to Yahweh:

And Jephthah vowed a vow unto the Lord, and said, If thou shalt without fail deliver the children of Ammon into mine hands. Then it shall be, that whatsoever cometh forth of the doors of my house to meet me, when I return in peace from the children of Ammon, shall surely be the Lord's, and I will offer it up for a burnt offering. (Judges 11:30-31)

Jephthah is duly victorious. He returns home, where the first person to greet him is his own daughter—named Sheïlah (שְאֵילָה [Seelah]) according to Pseudo-Philo (Ginzberg 4:44 : Gaster 177):

And Jephthah came to Mizpeh unto his house, and, behold, his daughter came out to meet him with timbrels and with dances: and she was his only child; beside her he had neither son nor daughter. And it came to pass, when he saw her, that he rent his clothes, and said, Alas, my daughter! thou hast brought me very low, and thou art one of them that trouble me: for I have opened my mouth unto the Lord, and I cannot go back. (Judges 11:34-35)

His daughter dutifully accepts her fate , requiring only two months to bewail her virginity:

And he said, Go. And he sent her away for two months: and she went with her companions, and bewailed her virginity upon the mountains. And it came to pass at the end of two months, that she returned unto her father, who did with her according to his vow which he had vowed: and she knew no man. And it was a custom in Israel, That the daughters of Israel went yearly to lament the daughter of Jephthah the Gileadite four days in a year. (Judges 11:38-40)

The location of Mizpeh of Gilead is still unknown (Freedman 6082). In Pseudo-Philo’s account, Sheïlah bewails her virginity on Mount Telag or Tlag [תְלַג] (Ginzberg 4:44 : Gaster 178), which is believed to be an Aramaic name for Mount Hermon—about 100 km north of Gilead—meaning snow-capped (Gaster xcix).

Jephthah and Idomeneus

The story of Jephthah and his daughter is curiously reminiscent of the ancient Greek myth of Idomeneus and his son:

Apollodorus tells us that while Idomeneus, king of Crete, was away with his army at the siege of Troy, his wife Meda at home was debauched by a certain Leucus, who afterwards murdered her and her daughter, and, having seduced ten cities of Crete from their allegiance, made himself lord of the island and expelled the lawful king Idomeneus when, on bis return from Troy, he endeavoured to reinstate himself in the kingdom. The same story is told, almost in the same words, by Tzetzes, who doubtless here, as in so many places, drew his information direct from Apollodorus. The exile of Idomeneus is mentioned by Virgil, who says that the king, driven from his ancestral dominions, settled in the Sallentine land, a district of Calabria at the south-eastern extremity of Italy. The poet says nothing about the cause of the king’s exile; but his old commentator Servius explains it by a story which differs entirely from the account given by Apollodorus. The story is this.

When Idomeneus, king of Crete, was returning home after the destruction of Troy, he was caught in a storm and vowed to sacrifice to Neptune whatever should first meet him; it chanced that the first to meet him was his own son, and Idomeneus sacrificed him or, according to others, only wished or attempted to do so; subsequently a pestilence broke out, and the people, apparently regarding it as a divine judgment on their king’s cruelty, banished him the realm. The same story is repeated almost in the same words by the First and Second Vatican Mythographers, who clearly here, as in many places, either copied Servius or borrowed from the same source which he followed. But on one point the First Vatican Mythographer presents an interesting variation; for according to him it was not his son but his daughter whom the king first met and sacrificed, or attempted to sacrifice. (Frazer 394-395)

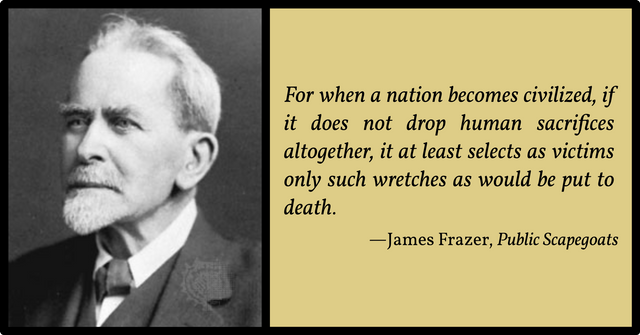

As the mythologist James Frazer notes, this is not the only myth that features this trope:

A similar story of a rash vow is told of a certain Maeander, son of Cercaphus and Anaxibia, who gave his name to the river Maeander. It is recorded of him that, being at war with the people of Pessinus in Phrygia, he vowed to the Mother of the Gods that, if he were victorious, he would sacrifice the first person who should congratulate him on his triumph. On his return the first who met and congratulated him was his son Archelaus, with his mother and sister. In fulfilment of his vow, Maeander sacrificed them at the altar, and thereafter, broken-hearted at what he had done, threw himself into the river, which before had been called Anabaenon, but which henceforth was named Maeander after him. The story is told by the Pseudo-Plutarch, who cites as his authorities Timolaus, in the first book of his treatise on Phrygia, and Agathocles the Samian, in his work, 7.6 Constitution of Pessinus. (Frazer 395-396)

Mention might also be made of the sacrifice of Iphigenia by her father Agamemnon before the Achaean fleet sails for Troy.

In Jephthah’s case, the intention from the beginning is to offer up a human being as a burnt offering:

In this last story, according to the only possible interpretation of the words, Maeander clearly intended from the outset to offer a human sacrifice, though he had not anticipated that the victims would be his son, his daughter, and his wife. Similarly in the parallel Israelitish legend of Jephthah’s vow it seems that Jephthah purposed to sacrifice a human victim, though he did not expect that the victim would be his daughter: “And Jephthah vowed a vow unto the Lord, and said, If thou wilt indeed deliver the children of Ammon into mine hand, then it shall be, that whosoever cometh forth of the doors of my house to meet me, when I return in peace from the children of Ammon, he shall be the Lord’s, and I will offer him up for a burnt offering.” For so the passage runs in the Hebrew original, in the Septuagint, and in the Vulgate and so it has been understood by the best modern commentators. In the sequel Jephthah did to his daughter according to his vow, in other words he consummated the sacrifice. “Early Arabian religion before Mohammed furnishes a parallel: ‘Al-Mundhir [king of al-Hirah] had made a vow that on a certain day in each year he would sacrifice the first person he saw; ‘Abid came in sight on the unlucky day, and was accordingly killed, and the altar smeared with his blood.’” (Frazer 396-397)

Frazer recounts several similar stories from folklore. Most of these folktales have happy endings, but Frazer suspects revisionism:

Thus in most of the folk-tales the rash vow turns out fortunately for the victim, who, instead of being sacrificed or killed, obtains a princely husband and wedded bliss. Yet we may suspect that these happy conclusions were simply devised by the story-teller for the sake of pleasing his hearers, and that in real life the custom, of which the stories preserve a reminiscence, often ended in the sacrifice of the victim at the altar. Of such a custom a record seems to survive in the legends of Idomeneus, Maeander, al-Mundhir, and Jephthah. (Frazer 404)

We have already noted a number of curious parallel between Greek mythology and the Old Testament:

Phineus and Phinehas.

The Danites and the Danaids.

And we will find more when we come to study the twelfth Judge of Israel, Samson. Also, the Greek alphabet was of Canaanite origin.

Jephthah and the Ephraimites

The story of Jephthah has an epilogue, which is almost as memorable as the story of his daughter:

And the men of Ephraim gathered themselves together, and went northward, and said unto Jephthah, Wherefore passedst thou over to fight against the children of Ammon, and didst not call us to go with thee? we will burn thine house upon thee with fire.

And Jephthah said unto them, I and my people were at great strife with the children of Ammon; and when I called you, ye delivered me not out of their hands. And when I saw that ye delivered me not, I put my life in my hands, and passed over against the children of Ammon, and the Lord delivered them into my hand: wherefore then are ye come up unto me this day, to fight against me?

Then Jephthah gathered together all the men of Gilead, and fought with Ephraim: and the men of Gilead smote Ephraim, because they said, Ye Gileadites are fugitives of Ephraim among the Ephraimites, and among the Manassites.

And the Gileadites took the passages of Jordan before the Ephraimites: and it was so, that when those Ephraimites which were escaped said, Let me go over; that the men of Gilead said unto him, Art thou an Ephraimite? If he said, Nay; Then said they unto him, Say now Shibboleth: and he said Sibboleth: for he could not frame to pronounce it right. Then they took him, and slew him at the passages of Jordan: and there fell at that time of the Ephraimites forty and two thousand. (Judges 12:1-6)

Nowhere in the previous chapter is there any mention of the Ephraimites: Jephthah does not in fact call upon their aid, as he here claims to have done. This alone suggests that this story was originally an independent narrative, quite unconnected with Jephthah. It has been argued that the story, which presents Jephthah in a negative light, was a later piece of propaganda directed by the Kingdom Judah against the northern Kingdom of Israel and drawing upon the accounts of two earlier judges:

This conflict mirrors Gideon’s conflict with Ephraim (8.1-3) and presents Ephraim negatively in a struggle for inter-tribal hegemony. Within the broader book, this fits the pro-Judean, anti-northern ideology of the editor. (Ephraim is used elsewhere in the Bible to refer to the Northern Kingdom.) While Gideon succeeded in preventing a civil war, Jephthah conducted a bloody conflict. The blocking of the Jordan crossings was a tactic used by Ehud (3-28), but while Ehud made war against the Moabites, Jephthah did so against his own people. These comparisons stress that Jephthah is not fit to lead. (Berlin & Brettler 538)

In English translations, the phonetic distinction is between [s] and [ʃ], but in the Hebrew text the distinction is between samekh [ס] and undotted sin [ש], both of which are pronounced similarly to our [s] (Clarke 156).

Although Jephthah is one of the major judges and a prominent figure in the Old Testament, he is assigned a very short term of office:

And Jephthah judged Israel six years. (Judges 12:7)

This has been interpreted as a negative commentary on Jephthah’s judgeship. His illegitimacy, his willingness to practise human sacrifice, his leadership of a band of ruffians, and his slaughter of 42,000 Ephraimites all paint him in a poor light that is at odds with the generally favorable portrayals of the other Judges:

While Jephthah the commander did indeed save his people from the Ammonites, he did not prove himself as a leader, and his term only lasted six years. (Berlin & Brettler 539)

The sacrifice of his virgin daughter—his only child—means that he dies without issue. This is another stain on his reputation.

This negative view of Jephthah is common in rabbinical literature (Singer 94-95 : Ginzberg 6:203). The compilers of the Book of Judges, however, may have seen him in a more favourable light. One commentator, for example, has noted similarities between Jephthah and David:

After the death of his father he was expelled from his home by the envy of his brothers, who, taunting him with illegitimacy, refused him any share of the heritage, and he withdrew to the land of Tob, beyond the frontier of the Hebrew territories. It is clear that he had before this distinguished himself by his daring character and skill in arms; for no sooner was his withdrawal known than a great number of men of desperate fortunes repaired to him, and he became their chief. His position was now very similar to that of David when he withdrew from the court of Saul. To maintain the people who had thus linked their fortunes with his, there was no other resource than that sort of brigandage which is accounted honorable in the East, so long as it is exercised against public or private enemies, and is not marked by needless cruelty or outrage. So Jephthah confined his aggressions to the borders of the small neighboring nations, who were in some sort regarded as the natural enemies of Israel, even when there was no actual war between them. (McClintock & Strong 818)

Then died Jephthah the Gileadite, and was buried in one of the cities of Gilead. (Judges 12:7)

The fact that his burial place is not explicitly identified as his home city of Mizpeh suggests that this passage is of different provenance than the rest of this chapter. The Hebrew text literally translates as in cities of Gilead (Ellicott 238), which may be the source of a curious legend concerning the manner of Jephthah’s death:

Jephthah died a horrible death. Limb by limb his body was dismembered. (Ginzberg 4:46)

Conclusion

The story of the Judgeship of Jephthah is beset with anomalies and inconsistencies similar to those that we find in the accounts of the other judges. In the opinion of most critics, the account is not a uniform one (Singer 95). This lends support to my thesis that the Book of Judges is unhistorical. If there is any historical truth to the story, it is probably only of local relevance to Gilead and probably belongs to an earlier period of Canaanite history, before the Joshuan Conquest.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), The Jewish Study Bible, Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Adam Clarke, The Holy Bible ... With a Commentary and Critical Notes, Volume 2, G Lane & P P Sandford, New York (1843)

- Charles John Ellicott (editor), An Old Testament Commentary for English Readers, Volume 2, Cassell & Company, Limited, London (1883)

- James George Frazer, Apollodorus: The Library, Volume 2, The Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann, London (1921)

- David Freedman (editor-in-chief), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, Doubleday, New York (1992)

- Moses Gaster (translator), The Chronicles of Jerahmeel, The Royal Asiatic Society, London (1899)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 4, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1913)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 6, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1928)

- Ken Johnson, Ancient Seder Olam: A Christian Translation of the 2000-year-old Scroll, Xulon Press, Maitland, FL (2006)

- John McClintock, James Strong, Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 4, Harper & Brothers, New York (1872)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 3, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 7, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1904)

- James Strong, Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, in The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

Image Credits

- Jephthah: Guillaume Rouillé, Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum, Part 1, Page 52, Lyon (1553), Public Domain

- The Amorites and the Bashanites: © Janz (designer), Creative Commons License

- Canaan after the Conquest: Edward Weller (cartographer), Charles John Ellicott (editor), An Old Testament Commentary for English Readers, Volume 2, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co, London (1883), Public Domain

- Jephthah and the Ammonites: Nicolaes Ryckmans (engraver), Battle between Jephthah’s Army and the Ammonites (1643), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Public Domain

- Jephthah Meets His Daughter: Hieronymus Francken III (artist), Private Collection, Public Domain

- The Return of Idomeneus: Jacques Gamelin (artist), Musée des Augustins Palais Niel, Toulouse, Léna (photographer), Public Domain

- James Frazer: Anonymous Photograph (1933), Public Domain

- A Ford of the River Jordan: Postcard, Public Domain

- Shibboleth: © Kevin Rolly (artist), Fair Use