Samson, the twelfth Judge of Israel, is one of the Bible’s most famous characters. Who is not familiar with the tale of Samson and Delilah? How this Hercules of Israel was seduced by his lover and how she discovered that the secret of his strength lay in his long hair? How she betrayed him to his implacable enemies the Philistines? How his hair was cut and his eyes put out and how he was forced to grind grain in a prison at Gaza? How his hair grew back, restoring his strength? How he pulled down the columns in the Temple of Dagon, and collapsed the building, killing himself and three thousand Philistines?

But is this tale true?

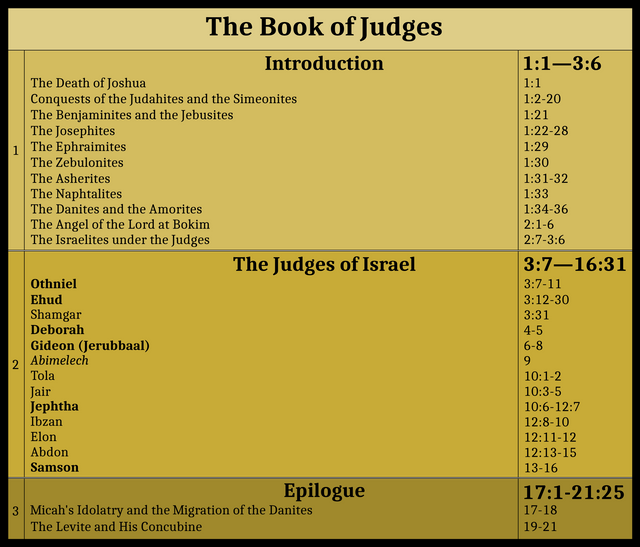

It has long been recognized that the Samson Cycle, as it is called, is quite different from the other narratives in the Book of Judges:

Samson was different from the other judges. His activity bears a miraculous character, he fights as an individual rather than a commander, and his heroic acts are the result of personal involvement with Philistine women. The stories concerning him are filled with remnants of myth, legends, and folk traditions. On the other hand, he is not portrayed as a giant, and he has a direct connection with God, both through his being a Nazirite and through his prayers. Concluding the stories of the judges with a hero who does not deliver his people but only himself, and who dies in enemy captivity, contributes to the feeling of disappointment with the type of leadership that the judges represent. This bolsters the book’s ultimate conclusion, that permanent kingship over all of Israel must be established. This cycle, like the others in the book, comprises originally distinct stories; for example, his status as a Nazirite is only operative in the first and last stories. In their final form here, they have been structured to focus on three subjects: his birth (ch 13), women in his life (chs 14-15), and his death (ch 16). (Berlin & Brettler 526)

Samson’s historicity has been questioned even by some Jewish scholars:

Even in the Talmudic period many seem to have denied that Samson was a historic figure; he was apparently regarded as a purely mythological personage. A refutation of this heresy is attempted by the Talmud (B. B. [l.c.), which gives the name of his mother, and states that he had a sister also, named “Nishyan” or “Nashyan” (variant reading, נשיק [n.sh.y.q]; this apparently is the meaning of the passage in question, despite the somewhat unsatisfactory explanation of Rashi). (Singer 2)

Solar Deity

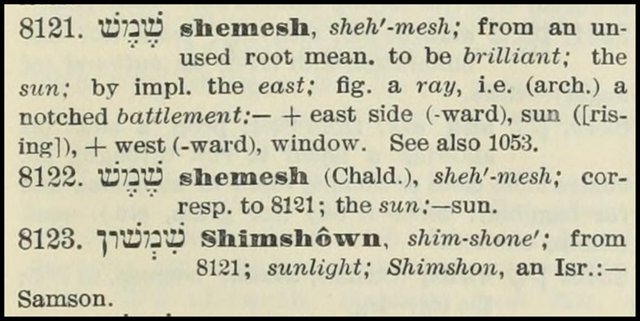

It has long been accepted that Samson’s name is closely related to the name of the Babylonian Sun god Shamash. The Hebrew form of his name שִׁמְשׁוֹן [shimshown] is derived from the Hebrew for sun: שֶׁמֶשׁ [shemesh]. James Strong interprets it as sunlight:

James Orr gives a slightly different etymology:

SAMSON ... derived probably from שֶׁמֶשׁ, shemesh, “sun,” with the diminutive ending וֹן-, -ōn, meaning “little sun” or “sunny,” or perhaps “sun-man”; (Orr 2675)

James L Crenshaw, Professor of the Old Testament at Duke University Divinity School and the author of the article on Samson in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, agrees:

The name Samson appears to be a diminutive form of šemeš (sun), hence “little sun.” Various features of the story suggest a connection at some stage with solar worship: e.g., Šamaš the sun god; the city Beth-shemesh (lit. “house/temple of the sun [god]’’); the blinding of Samson, analogous to a solar eclipse; the similarity between Delilah’s name and the Hebrew word for night (laylâ). The prominence of fire in the episodes further strengthens the hypothesis of solar mythology, as does the incident of the foxes, which recalls a ritual for preventing mildew reported to have taken place during the Roman festival of Cerealia. (Freedman 7775-7776)

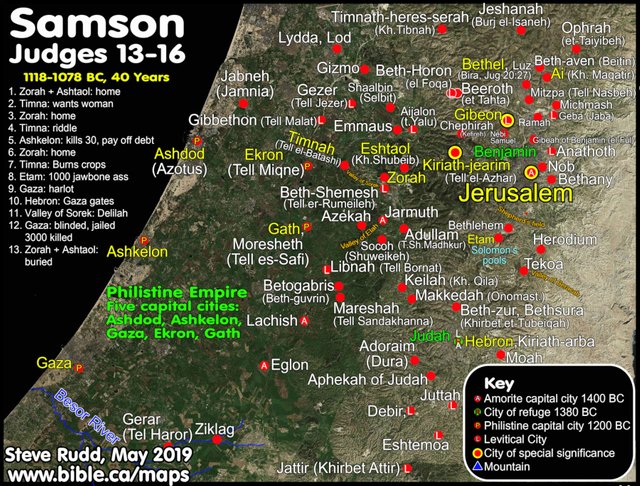

Samson’s birthplace, Zorah, identified with the depopulated Palestinian village of Sar’a, is only about 3 km north of Beth Shemesh. Other places featured in the Samson Cycle lie in the same locality, about 20 km west of Jerusalem:

Timnath, where Samson married his first wife.

Nahal Sorek, the river-valley in which Delilah lived.

Eshtaol, a city close to the place where Samson was first moved by the spirit of the Lord.

The Rock of Etam, where Samson hid from the Philistines.

Lehi, where Samson slew a thousand Philistines with the jawbone of an ass.

Before he pulls down the Temple of Dagon, Samson prays to God:

And Samson called unto the Lord, and said, O Lord God, remember me, I pray thee, and strengthen me, I pray thee, only this once, O God, that I may be at once avenged of the Philistines for my two eyes. (Judges 16:28)

The literal translation of the Hebrew is curious:

For my two eyes.—The words rendered “at once” in the previous clause may be rendered “that I may avenge myself the revenge of one of my two eyes.” If so, there seems to be in the words a grim jest, as though no vengeance would suffice for the fearful loss of both his eyes (LXX., “one revenge for my two eyes”), “one last tremendous deed, one last fearful jest.” There is a curious parallel to this achievement of Samson in the story of Cleomedes of Astypalaea, who in revenge for a fine pulls down a pillar, and crushes the boys in a school (Pausanias, Hellados Periegesis 6:9:6). Cassel tells us that on July 21st, 1864, many people were killed by the breaking of a granite pillar in the Church of the Transfiguration at St. Petersburg. (Ellicott 252)

It is possible that this detail reflects the fact that Samson was originally a one-eyed solar deity—like the Cyclops of Greek mythology or the Sun god of Celtic mythology—and lost only the one eye, like Polyphemus in the Odyssey:

From its shape and brightness the sun was regarded as the divine Eye of the heavens; hence we understand how the Irish word súil, which etymologically means ‛sun’, and is cognate with Welsh haul, Latin sol, etc., has acquired the meaning ‛eye’. When conceived anthropomorphically, the deity was often regarded as a huge one-eyed being ... [Footnote 5: So in Teutonic religion the far-travelling Odin (Wodan) is one-eyed, i.e. the sun-god, in addition to being lord of Valhalla and father of men. We have a Greek counterpart in the Kyklōpes, who, according to Hesiod, were three in number, their names Argēs (‛shining’), Steropēs (‛lightening’) and Brontēs (‛thundering’), and who forged the thunderbolts of Zeus. Originally there was but one Kyklōps, who, as his name (‛round-eyed’) suggests, was the sun-god, and consequently the source of lightning.] (O’Rahilly 58-59)

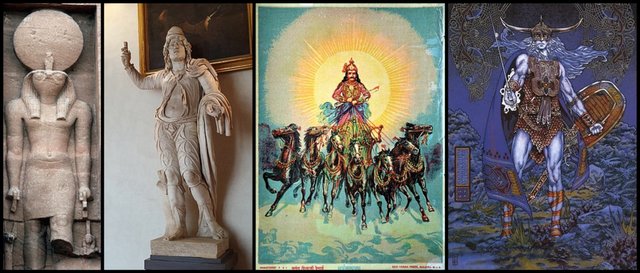

Samson’s long hair supports this interpretation, and is the reason he was regarded as a Nazirite. Long-haired sun-gods can be found in many cultures. For example: Ra-Horakhty. Attis, Surya, and Lugh. According to one theory, the long hairs represent the rays of the sun. According to another, they represent the coronal streamers that are visible during a solar eclipse.

Judges 16:13 mentions the seven locks of my head: compare this to the radiant crown of the Greek sun-god Helios, which was often depicted with seven spikes.

Iconotropy

In his classic study of Greek mythology, Robert Graves often explains a myth as a misreading of an icon. In the historical commentary to his semi-historical novel King Jesus, Graves calls this practice Iconotropy:

The long dialogue in Chapter Nineteen, between Jesus and Mary, may puzzle readers who do not know their Bible or Bible origins well. I am here suggesting a new theory of the composition of the early historical books: that to the parts not already existing in, say, the ninth century b.c. in the form of ballads or prose-epics were added anecdotes based on deliberate misinterpretation of an ancient set of ritual icons, captured by the Hebrews when they seized Hebron from the “Children of Heth”, whoever these people may have been. A similar technique of misinterpretation—let us it iconotropy—was adopted in ancient Greece as a means of confirming the Olympian religious myths at the expense of the Minoan ones which they superseded. For example, the story of the unnatural union of Pasiphaë (“She who shines for all”) and the bull, the issue of which was the monstrous Minotaur, seems to be based on an icon of the sacred marriage between Minos, the King of Cnossus (pictured with a bull’s head), and the representative of the Moon-goddess, in the course of which a live bull was sacrificed. The story of the rape of Europa (“Broadface”) by Zeus disguised as a bull belongs to a companion icon—an example of which has been found in a pre-Hellenic burial near Midea—showing the same Goddess riding on a bull. Again, the story of Oedipus (“Club-foot”) and the Sphinx who committed suicide when he guessed her riddle seems to be based on an icon of the Lame King (Hephaestus) adoring the Triple Goddess of Thebes after having killed his predecessor Laertes. The riddle, “four legs at dawn, two legs at noon and three legs at sunset”, suggests an attached cartoon showing a child, a youth and an old man with a staff—the meaning of which is that the Triple Goddess is man’s sovereign from the cradle to the grave.

In iconotropy the icons are not defaced or altered, but merely interpreted in a sense hostile to the original cult. The reverse process, of reinterpreting Olympian or Jahvistic patriarchal myths in terms of the mother-right myths which they have displaced, leads to unexpected results. (Graves 355)

I believe that the familiar story of Samson pulling down the Temple of Dagon is another example of iconotropy. The myth portrayed by the icon is the Greek story of the Pillars of Heracles. The Sun god—Atlas, Heracles—erects two great pillars, one at the eastern end of the world where the Sun rises and one at the western end where he sets. Upon these pillars he raises the firmament, or vault of the heavens:

Aeschylus tells us of the “Pillar of Heaven and Earth,” that is, the pillar which, resting on earth, supported the vault of heaven, and which was upborne by Atlas (Prometheus Bound 349, 428). (Smith 1054)

In Classical times, the Pillars of Hercules were generally associated with the Strait of Gibraltar, but in earlier times they had also been associated with the Bosporus Strait. In most accounts the Tenth Labour of Hercules—The Cattle of Geryon—took place in the far west, but the toponym Bosporus means Cattle Passage, and is thought by some to refer to the same Labour (Tony O’Connell).

These two Pillars of the Sun may also be identical to Boaz and Jachin, the two great columns that stood at the entrance to the Temple of Solomon. In Freemasonry these remain a potent symbol—though of what I cannot say.

The pagan icon, therefore, of the strong, long-haired Sun god standing between two pillars was reinterpreted by the Israelites as a hero pulling down a pagan temple. Whether this was a deliberate distortion of a pagan myth, as Graves’ definition of iconotropy implies, or an ignorant but innocent attempt to interpret a religious icon is neither here nor there.

The similarity of Samson and Heracles (or Hercules) has often been noted (eg Orr 2675, McClintock & Strong 315, Freedman 7776, Clarke 172). Several scholars—eg Georg Gustav Roskoff, Ernst Bertheau, Hans Bauer, Johann Karl Wilhelm Vatke, Heinrich Ewald—have even connected the deeds of Samson with the Twelve Labours of Heracles. Other commentators, however, have strenuously resisted these efforts:

Nor can it be made out, without arbitrary combination, that twelve of his acts are recorded (Bertheau). The attempts to draw out a parallel (as Roskoff has done) between the acts of Samson and the labours of Hercules is entirely valueless and unsuccessful, although, as will be seen ... parts of his story may have crept into Greek legends through the agency of Phoenician traders, and though certain features in his character—e.g., its genial simplicity and amorous weakness—resemble those of the legendary Greek hero. The narrative is in great measure biographical. (Ellicott 239)

A similar instance of iconotropy—involving the same icon—may also lie behind the following curious passage in the Book of Judges:

Then went Samson to Gaza, and saw there an harlot, and went in unto her. And it was told the Gazites, saying, Samson is come hither. And they compassed him in, and laid wait for him all night in the gate of the city, and were quiet all the night, saying, In the morning, when it is day, we shall kill him. And Samson lay till midnight, and arose at midnight, and took the doors of the gate of the city, and the two posts, and went away with them, bar and all, and put them upon his shoulders, and carried them up to the top of an hill that is before Hebron. (Judges 16:1-3)

The Tenth Labour of Hercules is often located at Cádiz, close to the Strait of Gibraltar. Could the ancient name of this city, Gadir, be the same as the Gaza of the Samson Cycle? It is interesting that Sebald Beham’s 16th-century engraving of Hercules carrying the Gaditanas Columnas [Columns of Cádiz] in generally known in English as Hercules Carrying the Columns of Gaza:

Conclusion

I believe that the story of Samson is myth, not history. There never was any such individual.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), The Jewish Study Bible, Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Ernst Bertheau, Das Buch der Richter und Ruth, S Hirzel, Leipzig (1883)

- Adam Clarke, The Holy Bible ... With a Commentary and Critical Notes, Volume 2, G Lane & P P Sandford, New York (1843)

- Gary G Cohen, Samson and Hercules, Evangelical Quarterly, Volume 42, Number 3, Pages 131-141, Paternoster Press, Milton Keynes (1970)

- Charles John Ellicott (editor), An Old Testament Commentary for English Readers, Volume 2, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co, London (1883)

- David Freedman (editor-in-chief), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, Doubleday, New York (1992)

- Robert Graves, King Jesus, Cassell and Company Limited, London (1946)

- John McClintock, James Strong, Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 9, Harper & Brothers, New York (1879)

- Tony O’Connell, Pillars of Herakles, Atlantipedia, Online, (2020)

- Thomas Francis O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 4, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- Georg Gustav Roskoff, Die Simsonfrage nach ihrer Entstehung, Form und Bedeutung und der Heraclesmythus [The Origin, Form and Meaning of the Samson Question and the Myth of Heracles], Leipzig (1860)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 11, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1905)

- William Smith (editor), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, Volume 1, John Murray, London (1873)

- James Strong, Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, in The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

Image Credits

- Samson: Guillaume Rouillé, Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum, Part 1, Page 57, Lyon (1553), Public Domain

- Samson and Delilah: Peter Paul Rubens (artist), National Gallery, London, Public Domain

- Places Mentioned in the Samson Cycle: © Steve Rudd (designer), Fair Use

- Samson Destroys the Temple of Dagon: Charles François Prosper Guérin (artist), Private Collection, Public Domain

- Ra-Horakhty: Anonymous Photograph, Abu Simbel, Fair Use

- Attis: Anonymous Greek Statue (2nd Century CE), Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Yair Haklal (photographer), Public Domain

- Surya: Raja Ravi Varma (lithographer), Ravi Varma Press, Malavli, Public Domain

- Lugh: The Coming of Lugh, © Jim FitzPatrick (artist), Fair Use

- Helios: 1st-Century Bust of Helios, Louvre Museum, Marie-Lan Nguyen (photographer), Public Domain

- Robert Graves: Datenbank Tripota, Robert Graves, Good-Bye to All That: An Autobiography, Frontispiece, Jonathan Cape, London (1929), Public Domain

- Rishi Sunak Adopts a Masonic Pose: © Tolga Akmen (photographer), EPA-EFE/Shutterstock, Fair Use

- Hercules Carrying the Columns of Gaza: Sebald Beham (engraver), Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Elizabeth, Julie, and Catherine Andrus in Memory of John and Marion Andrus, Public Domain