Samuel, the fourteenth and final Judge of Israel, is one of the better known figures in the Old Testament. Two books of the Bible are named for him—in the original Hebrew Bible they comprise a single book, Sefer Shmuel. Jewish tradition ascribes most of the contents of these books to Samuel himself. He is also said to have penned two other books of the Bible: Judges and Ruth. The importance of the rôle he is alleged to have played in the history of Israel is beyond dispute: it was Samuel who anointed the first two Kings of Israel, Saul and David, bringing to an end the Period of the Judges and inaugurating the United Monarchy. Samuel was both the last of the Judges and the first of the Prophets, a priest and a seer.

But did Samuel really exist and do all the things that are recorded of him?

Samuel in the Bible

The story of Samuel as told in the Old Testament may be quickly recounted:

Samuel was the son of Elkanah and Hannah, of Ramathaim-zophim, in the hill-country of Ephraim ... He was born while Eli was judge. Devoted to YHWH in fulfilment of a vow made by his mother, who had long been childless, he was taken to Shiloh by Hannah as soon as he was weaned, to serve YHWH during his lifetime ...

Eli, old and dim of vision, had lain down to sleep, as had Samuel, in the Temple of YHWH, wherein was the Ark. Then YHWH called “Samuel!” Answering, “Here am I,” Samuel, thinking Eli had summoned him, ran to him explaining that he had come in obedience to his call. Eli, however, sent him back to his couch. Three times in succession Samuel heard the summons and reported to Eli, by whom he was sent back to sleep. This repetition finally aroused Eli’s comprehension; he knew that YHWH was calling the lad. Therefore he advised him to lie down again, and, if called once more, to say, “Speak, for Thy servant heareth.” Samuel did as he had been bidden. YHWH then revealed to him His purpose to exterminate the house of Eli.

Samuel hesitated to inform Eli concerning the vision, but next morning, at Eli’s solicitation, Samuel related what he had heard ... YHWH was with Samuel, and let none of His words “fall to the ground.” All Israel from Dan to Beer-sheba recognized him as appointed to be a prophet of YHWH; and Samuel continued to receive at Shiloh revelations which he imparted to all Israel. (Singer 5)

The extermination of the house of Eli was accomplished during the war with the Philistines, who had been oppressing the Israelites for twenty years:

During the war with the Philistines the Ark was taken by the enemy. After its mere presence among the Philistines had brought suffering upon them, it was returned and taken to Kirjath-jearim. While it was there Samuel spoke to the children of Israel, calling upon them to return to YHWH and put away strange gods, that they might be delivered out of the hands of the Philistines ...

The test came at Mizpah, where, at Samuel’s call, all Israel had gathered, under the promise that he would pray to YHWH for them, and where they fasted, confessed, and were judged by him ... Before the Philistines attacked, Samuel took a sucking lamb and offered it for a whole burnt offering, calling unto YHWH for help; and as the Philistines drew up in battle array YHWH “thundered with a great thunder” upon them, “and they were smitten before Israel.” As a memorial of the victory Samuel set up a stone between Mizpah and Shen, calling it “Ebenezer” (= “hitherto hath the Lord helped us”). This crushing defeat kept the Philistines in check all the days of Samuel. (Singer 5-6)

There ensued a long period—eleven years according to the Seder Olam Rabbah— of peace, during which Samuel continued to judge Israel from Ramah (ie his birthplace Ramathaim-Zophim), where he built an altar. It was originally his hope that he would be succeeded by his two sons, Joel and Abijah, but when he was old and approaching death they proved unworthy:

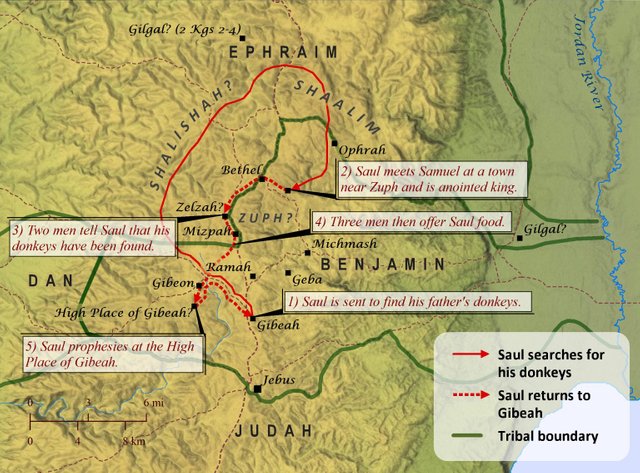

... they “turned aside after lucre, and took bribes” ... This induced the elders to go to Ramah and request Samuel to give them a king, as all the other nations had kings ... In this crisis Samuel met Saul, who had come to consult him, the seer, concerning some lost asses. YHWH had already apprised him of Saul’s coming, and had ordered him to anoint his visitor king. When Saul inquired of him the way to the seer’s house, Samuel revealed his identity to the Benjamite, and bade him go with him to the sacrificial meal at the “high place,” to which about thirty persons had been invited. He showed great honor to Saul, who was surprised and unable to reconcile these marks of deference with his own humble origin and station. The next morning Samuel anointed him, giving him “signs” which, having come to pass, would show that God was with him, and directing him to proceed to Gilgal and await his (Samuel’s) appearance there. (Singer 6)

Saul’s reign was not a happy one and the relationship between the two men was difficult from the start. They fell out when Saul offered sacrifice alone and later spared the life of Agag, the King of the Amalekites:

Thereupon the word of YHWH came unto Samuel, announcing Saul’s deposition from the throne. Meeting Saul, Samuel declared his rejection and with his own hand slew Agag ... This led to the final separation of Samuel and Saul ... Mourning tor Saul, Samuel was bidden by YHWH to go to Jesse, the Beth-lehemite, one of whose sons was chosen to be king instead of Saul ... Fearing lest Saul might detect the intention, Samuel resorted to strategy, pretending to have gone to Beth-lehem in order to sacrifice. At the sacrificial feast, after having passed in review the sons of Jesse, and having found that none of those present was chosen by YHWH, Samuel commanded that the youngest, David, who was away watching the sheep, should be sent for. As soon as David appeared YHWH commanded Samuel to anoint him, after which Samuel returned to Ramah. (Singer 6)

Samuel’s part is the history of Israel was largely concluded with the anointing of David, as the conflict between Saul and David took centre stage. He died shortly after:

The end of Samuel is told in a very brief note: “And Samuel died, and all Israel gathered themselves together, and lamented him, and buried him in his house at Ramah” ... But after his death, Saul, through the witch of Endor, called Samuel from his grave, only to hear from him a prediction of his impending doom. (Singer 6)

In the Seder Olam Rabbah, it is calculated that Saul died four months after Samuel (Guggenheim 132, 135 : Johnson 27:68).

The Historicity of Samuel

Although most Biblical scholars accept that there is at the very least a kernel of historical truth in the story of Samuel, they have not hesitated to dispute many of the details:

The outline of the life of Samuel given in the First Book of Samuel is a compilation from different documents and sources of varying degrees of credibility and age, exhibiting many and not always concordant points of view. (Singer 7)

Samuel’s life is presented to us in the Bible with very little supporting chronology. We must turn to later rabbinical scholars to learn how many years he judged Israel (eleven) or how old he was when he died (fifty-two):

The Old Testament furnishes no chronological data concerning his life. (Singer 6)

This is in marked contrast to the accounts of his predecessors in the Book of Judges, which generally record the precise lengths of their successive Judgeships. Nevertheless, many scholars see Samuel’s Judgeship as the most credible part of his story:

The role with which the greatest number of scholars associate the historical Samuel is that of judge. 1 Sam 7:15 declares that “Samuel judged Israel all the days of his life,” an expression akin to that used of the so-called “minor judges” who are mentioned briefly in the book of Judges ... and whose activity is usually assumed to have been primarily judicial. This aspect of Samuel’s “judgeship” is credited by a number of commentators as rooted in historical fact ... (Freedman 7782)

Another discrepancy concerns the lineage of Samuel. His father Elkanah is from Ephraim, but Elkanah’s ancestor Zuph is from Ephrathah, which is usually identified with Bethlehem in Judah:

1 Sam. ch 1 indicates that Samuel was of either Ephraimite or, less plausibly, Judahite origin. (Berlin & Brettler 1725)

But I Chronicles 6:22-28 explicitly makes Elkanah and Samuel descendants of Levi’s son Kohath:

The appearance of Elkanah and the prophet Samuel in the list of Levites is unparalleled in other sources ... Chronicles’ revised position is informed by the fact that 1 Sam. chs 2-3 present Samuel as having ministered in the Shiloh Tabernacle, an activity typically identified with (later) Levitic service. Inasmuch as Torah law (e.g., Num. ch 18) proscribes cultic service by anyone not of Levitic descent, the author felt compelled to attach an explicit Levitic pedigree to Samuel. Some argue that 1 Samuel views Samuel’s family as a Levitical family hailing from Ephraim or Judah (Berlin & Brettler 1725)

Emil G Hirsch, who wrote the article on Samuel for The Jewish Encyclopedia, concludes his article with the following:

The Levitical genealogy of I Chron. vi. is not historical. (Singer 8)

The argument is that the historical Samuel lived at a time when the priesthood was not restricted to the Tribe of Levi, but when the Book of Samuel was compiled this restriction was in place and so it was necessary to provide him with a Levitical genealogy:

It is quite conceivable that, at a time when levitic ancestry was not a prerequisite for priestly service ... Samuel was apprenticing for the priesthood, but the calling of the Lord turned him to other forms of ministry. Later Israelites, assuming a priestly role for Samuel, assigned to him a levitic ancestry (1 Chr 6:7-13; contrast the lineage in 1 Sam 1:1) (Freedman 7783).

Arguably, Samuel’s most significant rôle in the history of Israel was not as Judge or Priest but as anointer of kings:

Since virtually all of the accounts surrounding the establishment of Saul’s kingship assign Samuel an instrumental role, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that he was a major figure in the transition to monarchy, but scholars are divided over where in these accounts genuine historical recollections are to be found. (Freedman 7783)

The anointing of Saul has been called into question on the grounds that this sort of ritual was foreign to the ancient Israelites:

As noted above, the references to Samuel in 9:1-10:16 [the anointing of Saul] are widely thought to have been inserted at a secondary stage of the tradition by prophetic editors. Some have suggested that the foreign origin of the anointing ritual, with its magical connotations, makes it unlikely that Samuel would have utilized the practice ... (Freedman 7783)

Moreover, the account of Saul’s first meeting with Samuel and his anointment (I Samuel 9:1-10:16) is immediately contradicted by another account in which Saul is chosen king by lot (I Samuel 10:17-27):

Several traditions of varying historical value seem to have been combined in 10:17-27. There is no reference elsewhere in the OT to choosing a king by lot, which is an unlikely way to select a king ... It seems more reasonable that Saul was identified via an oracle from God specifying the tallest man to be the divine nominee. Although 10:25 is often attributed (with reference to Deut 17:14-20) to later redactors, a fairly widespread interpretation is that this refers to a constitutional document spelling out royal regulations negotiated by Samuel with the popular assembly ... The prophetic oracle in vv 18-19 is usually regarded as an addition by prophetic or Deuteronomistic editors ... (Freedman 7783)

His Name

Samuel’s very name may also be artificial, casting doubt on his historicity:

The name “Shemu’el” is interpreted “asked of YHWH,” and, as Ḳimḥi suggests, represents a contraction of מאל שאול [m’l s’wl], an opinion which Ewald is inclined to accept (Lehrbuch der Hebräischen Sprache, p. 275, 3). But it is not tenable. The story of Samuel’s birth, indeed, is worked out on the theory of this construction of the name (i.1 et seq., 17, 20, 27, 28; ii.20). But even with this etymology the value of the elements would be “priest of El” (Jastrow, in “Jour. Bib. Lit.” xix.92 et seq.). Ch. iii. supports the theory that the name implies “heard by El” or “hearer of El.” The fact that “alef” and “ayin” are confounded in this interpretation does not constitute an objection; for assonance and not etymology is the decisive factor in the Biblical name-legends, and of this class are both the first and the second chapter. The first of the two elements represents the Hebrew term “shem” (= “name”); but in this connection it as often means “son.” “Shemu’el,” or “Samuel,” thus signifies “son of God” ... (Singer 7 : Strong 118)

Some scholars have even acknowledged a possible connection between the names Saul and Samuel:

In order to apply to him the title of “judge” in the sense it bore in connection with the heroes of former days—the sense of “liberator of the people”—the story of the gathering at Mizpah is introduced (vii.2 et seq.). Indeed, the temptation is strong to suspect that originally the name שאול (Saul) was found as the hero of the victory, for which later that of שמואל (Samuel) was substituted. (Singer 7)

Seer

It is possible, however, that some elements of Samuel’s story are historical:

The older strata in the story are more trustworthy historically than are the younger. In I Sam. ix.1-x.16 Samuel is a seer and priest at one of the high places; he is scarcely known beyond the immediate neighborhood of Ramah. Saul does not seem to have heard of him; it is his “boy” that tells him all about the seer (ix.). But in his capacity as seer and priest, Samuel undoubtedly was the judge, that is, the oracle, who decided the “ordeals” for his tribe and district. (Singer 7)

In this respect, it is curious that the Bible preserves the tradition that Samuel was believed by the local people to be able to reveal the whereabouts of lost animals. It was precisely in the hope of locating his strayed asses that Saul first approached Samuel—though some scholars believe that Samuel was only later substituted for an anonymous seer (Freedman 7782).

According to I Sam. ix. 9, the prophets preceding Samuel were called seers, while it would appear that he was the first to be known as “nabi,” or “prophet.” He was the man of God (ix. 7-8), and was believed by the people to be able to reveal the whereabouts of lost animals. In his days there were “schools of prophets,” or, more properly, “bands of prophets.” From the fact that these bands are mentioned in connection with Gibeah ... Jericho ... Ramah ... Beth-el ... and Gilgal ...—places focal in the career of Samuel—the conclusion seems well assured that it was Samuel who called them into being. (Singer 6)

Sons

Is it significant that Samuel’s two sons Joel and Abijah prove to be corrupt and unworthy of judging Israel, which lead’s Samuel to anoint Saul as King? The Judge Eli’s two sons Hophni and Phinehas had also proved unworthy, leading to the Judgeship of Samuel. The similarity between the two cases was noted by the commentator Charles Ellicott:

It is strange that the same ills that ruined Eli’s house, owing to the evil conduct of his children, now threatened Samuel. (Ellicott 321)

In The Legends of the Jews Louis Ginzberg notes another detail common to the two accounts. One of the brothers is censured for not correcting the other:

During his lifetime, his [Eli’s] youngest son Phinehas, the worthier of the two, officiated as high priest. The only reproach to which Phinehas laid himself open was that he made no attempt to mend his brother’s ways ... In a sense, therefore, the curse with which Eli threatened Samuel in his youth was accomplished: both he and Samuel had sons unworthy of their fathers. Samuel at least had the satisfaction of seeing his sons mend their ways. One of them is the prophet Joel, whose prophecy forms a book of the Bible. [Endnote: ... (the views differ; according to one opinion, both were wicked; while others maintain that when they repented, both were found worthy of receiving the gift of the holy spirit) ... See also ps.-Jerome., 1 Chron. 6.13; who (following Jewish tradition?) maintains that Abijah was an unworthy judge, but not his brother Joel, though he too is censured by Scripture for not having attempted to restrain his brother from his evil deeds. See a similar view with regard to the two sons of Eli, vol. IV, p. 61. (Ginzberg 4:61 ... 64-65, 6:229:46)

Are these doublets of the same story?

The rabbinical tradition that Samuel’s eldest son was Joel the Prophet, one of the so-called Minor Prophets of the Old Testament, is contradicted by the opening verse of the Book of Joel, which identifies this Joel as the son of Pethuel (Ginzberg 4:65 : Joel 1:1).

Geography

The identity of Samuel’s birthplace and burial place, which is referred to in the Book of Samuel as both Ramathaim-Zophim and Ramah, is still uncertain. Two places—both a few kilometres north of Jerusalem—have been proposed as the home town of Samuel:

Al-Nabi Samwil, a Palestinian village about 8 km northwest of Jerusalem. The name means The Prophet Samuel (Palmer 324). No remains from the Late Bronze Age—the period to which I would assign an historical Samuel—have been found here, but some pottery from the Iron I and II Ages has been excavated (Israel Antiquities Authority).

Al-Ram, a Palestinian town about 8 km north of Jerusalem. Its name means The Height or The Hill (Palmer 324). It is thought to be the same as the Ramah in Benjamin mentioned in Joshua 18:25 and Judges 19:13. No remains from the Late Bronze Age have been found, and only scanty remains from the Iron I Age (Israel Antiquities Authority).

These towns lay in the territory of the Tribe of Benjamin. I Samuel 1 says that Ramoth-Zophim was in Mount Ephraim, but this area extended from Ephraim into northern Benjamin, so there is no contradiction here (Ellicott 294). The Jewish historian Josephus distinguishes between Samuel’s birthplace and burial place, but he does not state explicitly that they were two different places:

Ramathaim, a city of the tribe of Ephraim. (Josephus 146) ...

They buried him in his own city of Ramah. (Josephus 171)

Some scholars believe that Josephus implies that these are two names for the same place (McClintock & Strong 896).

The city of Ramallah, which lies about 14 km north of Jerusalem, has also been proposed as a candidate. It has the merit of lying in the southern part of Mount Ephraim, though it too lies in the territory of Benjamin. Its modern name is Arabic for God’s Height, so it is plausible that it was known as Ramah in ancient times. Strong interprets Ramah as a height (as a seat of idolatry), the feminine active participle of a primitive root רום [rûwm], meaning to be high, to rise, to raise (Strong 109, 107). Ramathaim is the dual of Ramah, so Ramathaim-Zophim means double height of watchers (Strong 109).

As regards this famous subject of controversy, it is safest to say that we do not know where Ramathaim Zophim was; like all controversies, it arises from the fact that there is very little absolute information to be obtained on the subject. The main points to be observed seem to me to be: first, that the city was in Mount Ephraim; secondly, that a place called Sechu lay on the road from it to Gibeah [I Samuel 19:22]; thirdly, that Samuel belonged to the family of the Kohathites who possessed Beth Horon (1 Chron. vi. 67), from which it might be argued that his native town was probably near Beth Horon; lastly, that the name Ramathaim Zophim means “the [two] heights of the views,” so that it is natural to expect a position commanding an extensive prospect. These considerations seem to point to Râm Allah, east of Beth Horon on the west slopes of Mount Ephraim, overlooking the maritime plain, and in confirmation of this proposition we find a ruined village called Sueikeh, perhaps the Sechu of the Bible (1 Sam. xix. 22), on the high-road from Geba to Râm Allah. (Conder 116)

As Ramallah is still a thriving city, it has never been extensively excavated. The modern city only dates back to the 16th century, and the oldest remains are from the time of the Crusades. But the Palestinian historian Mustafa Murad al-Dabbagh, author of the Encyclopedia Biladuna Filastin [Our Land Palestine], has added his support to Conder:

According to Mustafa Murad al-Dabbagh, Ramallah is located in the area of “Ramtayim Sufim” (which he erroneously translates as the “two Sufi mounts,” whereas the Aramaic meaning is “overlooking hills”), mentioned in the Old Testament as the birthplace of the prophet Samuel. Others think it might possibly be Ramah, mentioned in the New Testament as the hometown of Joseph of Arimathea, where according to gospel accounts, he buried the body of Christ after the crucifixion in the grave prepared for his own use (Dabbagh, Biladuna, 234). Dabbagh relays an anonymous account that during the Roman period, two small villages sat on Ramallah’s current location: one of the villages, Gabaon, was located in the northern hills, while the second, Eleasa, was located on the southern hills (Dabbagh, Biladuna, 234).

This anonymous account may shed light on why the ancient city was called Ramathaim, or Two Heights. But has al-Dabbagh correctly identified his two small villages? Eleasa, which is mentioned in the First Book of the Maccabees (Chapter 9), is usually placed between Upper and Lower Beth-Horon, a good 10 km from the centre of Ramallah (International Standard Bible Encyclopedia Online). And Gabaon is the usual form in Greek of the name of the well-known city of Gibeon, which lies about 6 km south of central Ramallah. But another site has been proposed for Eleasa, Khirbet el-Ašši, by modern Ramallah, which is less than 2 km from the city centre (Freedman 312). On the following map, Zelzah, where Samuel told Saul he would meet two men with news that his missing asses had been found, is identified with Khirbet el-Ašši in modern Ramallah.

The early Christian historian Eusebius of Caesarea identified Ramathaim-Zophim with the Arimathea of the New Testament, which he located about 14 km northeast of Lod at a place called Remphis (Freeman-Grenville 26). This place has been identified with the Palestinian village of Rantis. Close to Rantis lie the ruins of Horvat Hani, or Khirbat Burj el-Haniyah, Ruin of the Tower of Haniyah, which are traditionally identified with the burial place of Samuel’s mother Hannah (Miriam Feinberg Vamosh

Sep 11, 2018). Rantis is in Ephraim.

It may be significant that Saul was a Benjaminite. Perhaps the references to Ephraim are misleading us. Mizpah, the city where Samuel and the Israelites atoned for worshipping strange gods, was also in Benjamin. The Madaba Mosaic Map, which was created in the 6th century, agrees with Eusebius in identifying Ramathaim-Zophim and Arimathea, but places this city in the vicinity of Al-Nabi Samwil and Ramallah (Wolf Endnote 144).

Conclusion

There is something very credible about a holy man in Mount Ephraim to whom local shepherds turned for advice whenever one of their animals strayed. Perhaps this is all the historical Samuel was. He was not the Second Moses of the Bible (Orr 2677, 2678), and his father Elkanah was not a Second Abraham (Ginzberg 4:57). The whole story, at least insofar as it is history, may belong entirely within the borders of Benjamin. Was Saul simply a local King of Benjamin?

Many of the places mentioned in Samuel’s story have names that imply an upland region: Ramah (height), Mizpah (watchtower), Shen (tooth, meaning crag). Mount Ephraim extends into the northern part of Benjamin.

On the other hand, the Kingdom of Israel certainly existed in historical times, so there must have been a point in time when it was first established. Was the first king anointed by a holy man, or did he simply make himself king by conquering his enemies on the battlefield? And if he was anointed—or, perhaps, appointed—by a holy man, was that holy man Samuel?

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), The Jewish Study Bible, Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Claude Reignier Conder, Tent Work in Palestine: A Record of Discovery and Adventure, Volume 2, Richard Bentley & Son, London (1879)

- Mustafa Murad al-Dabbagh, Biladuna Filastin, Volumes 1-11, Dar al-Tali'a in Beirut (1965-76)

- Charles John Ellicott (editor), An Old Testament Commentary for English Readers, Volume 2, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co, London (1883)

- Heinrich Ewald, Ausführliches Lehrbuch der Hebräischen Sprache des Alten Bundes, Fifth Edition, Hahn’sche Verlags-Buchhandlung, Leipzig (1844)

- David Freedman (editor-in-chief), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, Doubleday, New York (1992)

- G S P Freeman-Grenville (translator), The Onomasticon of Eusebius of Caesarea and the Liber Locorum of Jerome, Carta, Jerusalem (2003)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 4, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1913)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 6, Translated from the German by Henrietta Szold, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1928)

- Heinrich W Guggenheimer (translator & commentator), Seder Olam: The Rabbinic View of Biblical Chronology, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD (2005)

- Morris Jastrow, Jr, The Name of Samuel and the Stem שאל, Journal of Biblical Literature, Volume 19, Number 1, Pages 82-105, The Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, Georgia (1900)

- Ken Johnson, Ancient Seder Olam: A Christian Translation of the 2000-year-old Scroll, Xulon Press, Maitland, FL (2006)

- John McClintock, James Strong, Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 8, Harper & Brothers, New York (1879)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 4, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- Edward Henry Palmer, The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists, Collected by C R Conder & H H Kitchener, The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London (1881)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 11, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1905)

- James Strong, Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, in The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

- Carl Umhau Wolf, The Onomasticon of Eusebius Pamphili: Compared with the Version of Jerome and Annotated, Noel C Wolf, Online (1971)

Image Credits

- The Prophet Samuel: Claude Vignon (artist), Rouen Musée des Beaux Arts, Rouen, Public Domain

- Hannah Presents Her Son Samuel to the Priest Eli: Gerbrand van den Eeckhout (artist), Louvre Museum, Paris, Public Domain

- Kirjath-Jearim (Abu Ghosh): © Hagai Agmon-Snir [حچاي اچمون-سنير חגי אגמון-שניר] (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Samuel Anointing Saul: François de Nomé (artist), Harvard Art Museums, Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Public Domain

- The Witch of Endor Summons the Shade of Samuel: Dmitry Nikiforovich Martynov (artist), Ulyanovsk Regional Art Museum, Public Domain

- The Tomb of Samuel (Al-Nabi Samwil): © עמוס גל [Gal Amos] (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Saul Reproved by Samuel: John Singleton Copley (artist), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Public Domain

- Al-Ram (Ramah of Benjamin): G Eric & Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Public Domain

- Samuel Anoints Saul: Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Die Bibel in Bildern, Woodcut 89, Georg Wigand’s Verlag, Leipzig (1860), Public Domain

- Map of Canaan in the Time of Samuel: Alexander Francis Kirkpatrick, The Second Book of Samuel in the Revised Version, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1930)

- Al Manara Square in the Centre of Ramallah: © Joel Carillet (photographer), Fair Use

- A View of the Judean Hills from Ramallah: © Anthony Baratier (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Saul’s Journey in Search of His Strayed Asses: © David P Barrett (designer), Creative Commons License

- Benjamin in the Time of Samuel: © David P Barrett (designer), Creative Commons License