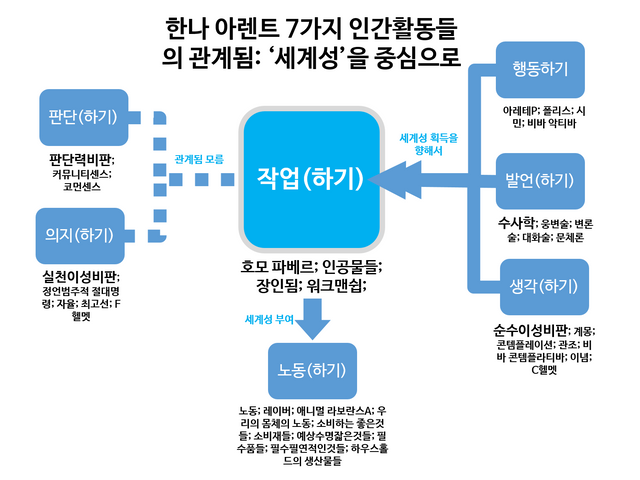

12.. 세계의 거시기-성격The Thing-character of the WorId

The contempt for labor in ancient theory and its glorification in modern theory both take their bearing from the subjective attitude or activity of the laborer, mistrusting his painful effort or praising his productivity. The subjectivity of the approach may be more obvious in the distinction between easy and hard work, but we saw that at least in the case of Marx— who, as the greatest of modern labor theorists, necessarily provides a kind of touchstone in these discussions— labor's productivity is measured and gauged against the requirements of the life process for its own reproduction; it resides in the potential surplus inherent in human labor power, not in the quality or character of the things it produces. Similarly, Greek opinion, which ranked painters higher than sculptors, certainly did not rest upon a higher regard for paintings.30 It seems that 노동과 작업 사이의 구별은... 생산된 거시기의 세계있음의 성질 또는 성격, 곧 그것의 장소, 그것의 기능, 세계 안에서 그것이 머무는 길이의 정도등급 안에서의 차이이다(122)the distinction between labor and work, which our theorists have so obstinately neglected and our languages so stubbornly preserved, indeed becomes merely a difference in degree if the worldly character of the produced thing— its location, function, and length of stay in the world— is not taken into account. 세계 안에서의 "예상수명"이 하루도 안되는 어떤 빵(노동의 생산물, 애니멀 라보란스)과 사람들의 몇세대를 쉽게 거치는 어떤 탁자(작업의 생산물; 호모 파베르)의 구별은 제빵사와 목수의 구별보다 일정하게 더 명확하고 결정적이다(172)The distinction between a bread, whose "life expectancy" in the world is hardly more than a day, and a table, which may easily survive generations of men, is certainly much more obvious and decisive than the difference between a baker and a carpenter.

- On the contrary, it is doubtful whether any painting was ever as much admired as Phidias' statue of Zeus at Olympia, whose magical power was credited to make one forget all trouble and sorrow; whoever had not seen it had lived in vain, etc.

The curious discrepancy between language and theory which we noted at the outset therefore turns out to be a discrepancy between the world-oriented, "objective" language we speak and the manoriented, subjective theories we use in our attempts at understanding. 비타 악티바가 스스로를 써버리는 곳인, 세계의 거시기들은 매우 다른 어떤 본성자연의 것이고, 그리고 활동들의 사뭇 다른 종류들에 의해 생산된다는 것을 우리에게 가르쳐주는 바, 그것은 그저 한낱 이론 따위가 아니라 그런 사실 아래 깔려있는 근본기초적인 인간경험들이고 언어이다 * 이것이 바로 <일언어>라고 여겨진다. 이 글줄 안 "이론"은 글언어라고 보면 되겠다(172)It is language, and the fundamental human experiences underlying it, rather than theory, that teaches us that the things of the world, among which the vita activa spends itself, are of a very different nature and produced by quite different kinds of activities. Viewed as part of the world, 그것들이 없으면 결코 존재할 수 없는, 어떤 세계의 영속성과 내구성을 보증하는 '그것들'이라는 것은, 노동의 생산물들이 아니라 작업의 생산물들이다(172)the products of work— and not the products of labor— guarantee the permanence and durability without which a world would not be possible at all. It is within this world of durable things that we find the consumer goods through which life assures the means of its own survival. Needed by our bodies and produced by its laboring, but without stability of their own, these things for incessant consumption appear and disappear in an environment of things that are not consumed but used, and to which, as we use them, we become used and accustomed. As such, they give rise to the familiarity of the world, its customs and habits of intercourse between men and things as well as between men and men. 소비자의 좋은것들(노동의 생산물들; 애니말 라보란스)이 사람의 생명삶을 위해 있다면, 쓸모있는 오브젝트들(작업의 생산물들; 호모 파베르)은 사람의 세계를 위해 있다(172)What consumer goods are for the life of man, use objects are for his world. 쓸모있는 오브젝트들로부터, 소비자의 좋은것들은 그것들의 거시기-성격을 갈래쳐받는다; (그렇지않다면) 노동하는 활동(애니멀 라보란스)으로하여금 어떠한것도 결코 그렇게 고체화되게 그리고 동사가 아닌 어떤 명사로써 형태화하도록 허락하지 않음을, 언어(가 말하고 있고)는 "우리의 손들의 작업(호모 파베르)"이라는 할만한 것을 우리 앞에 우리가 갖지 않는 이상, 심지어는 어떤 거시기가 무엇인지조차 우리가 알 수 없을 거라는 점을 강한 개연성으로 암시한다(172)From them, consumer goods derive their thing-character; and language, which does not permit the laboring activity to form anything so solid and non-verbal as a noun, hints at the strong probability that we would not even know what a thing is without having before us "the work of our hands."

소비자의 좋은것들 및 쓸모있는 오브젝트들, 이 둘과 구별되는, 마지막으로 행동의 '생산물들' 및 로고스(발언; 이성; 낱말)의 '생산물들'이 있다. 써그것들은 함께 인간의 관계됨들과 일들의 패브릭(짜임새)을 컨스티튜트한다(173)Distinguished from both, consumer goods and use objects, there are finally the "products" of action and speech, which together constitute the fabric of human relationships and affairs. Left to themselves, they lack not only the tangibility of other things, but are even less durable and more futile than what we produce for consumption. 행동과 발언(로고스)의 실재현실은 전적으로 인간의 여럿됨 상에, 그리고 보고 듣고 그래서 그것들의 실존을 증언해주는, 타자의 항상적인 현전 상에 종속된다(173)Their reality depends entirely upon human plurality, upon the constant presence of others who can see and hear and therefore testify to their existence. 행동하기와 발언하기는 인간생명삶의 바깥을향한 선언들이다(173)acting and speaking are still outward manifestations of human life, which knows only one activity that, though related to the exterior world in many ways, is not necessarily manifest in it and needs neither to be seen nor heard nor used nor consumed in order to be real: the activity of thought.

Viewed, however, in their worldliness, action, speech, and thought have much more in common than any one of them has with work or labor. They themselves do not "produce," bring forth anything, they are as futile as life itself. In order to become worldly things, that is, deeds and facts and events and patterns of thoughts or ideas, they must first be seen, heard, and remembered and then transformed, reified as it were, into things— into sayings of poetry, the written page or the printed book, into paintings or sculpture, into all sorts of records, documents, and monuments. The whole factual world of human affairs depends for its reality and its continued existence, first, upon (1)the presence of others who have seen and heard and will remember, and, second, on (2)the transformation of the intangible into the tangibility of things. Without remembrance and without (2')the reification which remembrance needs for its own fulfilment and which makes it, indeed, as the Greeks held, the mother of all arts, the living activities of action, speech, and thought would lose their reality at the end of each process and disappear as though they never had been. The materialization they have to undergo in order to remain in the world at all is paid for in that always the "dead letter" replaces something which grew out of and for a fleeting moment indeed existed as the "living spirit." They must pay this price because they themselves are of an entirely unworldly nature and therefore need the help of an activity of an altogether different nature; 행동, 발언(로고스), 생각의 살아있는 활동들은 그것들의 실재현실과 물질화를 위해, 다른 거시기들을 인간의 인공체 안에 지어내는 것과 동일한, 워크맨쉽(작업하는이됨)에 종속된다(174)they depend for their reality and materialization upon the same workmanship that builds the other things in the human artifice.

The reality and reliability of the human world rest primarily on the fact that we are surrounded by things more permanent than the activity by which they were produced, and potentially even more permanent than the lives of their authors. 인간생명삶은, 그것이 세계-짓기인 한, 항상적인 사물화의 어떤 과정 안에 참여한다. 그리고 모두 함께 인간의 인공체를 형태화하는, 생산된 거시기들의 세계있음의 정도등급은 세계 안에서의 더커다란 또는 덜커다란 영속성 그자체에 종속된다(174)Human life, in so far as it is world-building, is engaged in a constant process of reification, and the degree of worldliness of produced things, which all together form the human artifice, depends upon their greater or lesser permanence in the world itself.

● 이 3부 11장 안에서 아렌트는, 먼저 한번더 <노동 vs 작업>이 어떻게 다른지를 설명합니다. 먼저 아렌트는 노동의 생산물의 세계있음worldliness은 예상수명이 짧다는 점, 정반대로 작업의 그것은 길다는 점을 에로 듭니다.그다음으로 아렌트는 노동의 그것들 곧 소비자의 좋은것들(소비재)은 생활필수품에 그치는 반면, 작업의 그것들은 인간의 인공체들로써 세계의 지속성과 내구성을 보증하는 것들이라고 규정합니다. 더나아가 소비되는 좋은것들은 그것들의 거시기-성격 곧 세계있음을 작업된 인공체들로부터 수여받는다고 합니다(그 반대는 불가능함).이렇게 노동과 작업의 차이를 밝힌 다음, 아렌트는 행동, 발언, 생각(또는 이념)이라는 다른 또는 남아있는 인간활동들의 세계있음을 서술합니다. 이들 행동하기, 생각하기, 발언하기의 세계있음은 노동하기나 작업하기와는 무척 다른데,(1)타자들의 현전(2)만질수없는것들로부터 만져지는것들로의 트랜스포메이션( 곧 기억의 사물화)라는 과정들을 필요로 하며, 이러한 과정들 없이는 이들 3가지 활동들은 물질화될 수 없다고 아렌트는 생각합니다.그리고 11장 결론부에 이르는데, 아렌트는 여기서, 생각하기, 발언하기, 행동하기의 세계있음은 작업하기 상에 종속된다는 생각을 밝힙니다. 이렇게해서, 아렌트의 표상을 받아들인다면, 우리는 다섯가지 인간활동들(노동, 작업, 행동, 발언, 생각)이 어떻게 서로 관계되는지를 알 수 있게 됩니다.