Intro

The words we use (or do not use) is a good indicator of our mental prowess, and even more importantly, of the strength of our spirit.

The power of words was evident to the ancients, but we have largely forgotten it. The words that made up a name of a person were thought to control their destiny. To know the name of a god was equated with being able to make a claim on him (remember Moses?).

Here is something even more concrete. Have you ever thought about why we have names? Why not numbers (as in "Make it happen, Number One!"). Why not just "you guy" or "hey, girl"? Think of most traditional names - they all actually mean something. A lot of times it is a sign of character (Sophia - wisdom, Irene - peace, Peter - rock, Andrew - manly (and, by implication, strong, courageous). At other times it has some abstract, spiritual quality (Daniel - "God is my judge", Matthew - "gift of Yahweh", John - "Yahweh is gracious"). Including some popular names of Irish and Welsh descent, Jennifer is actually a transformed Guinevere (Gwenhwyfar in the original Welsh) which means a "white enchantress", Dylan - "strong tide/waves", Evan - "warrior". Well, you get the idea.

Names illustrate the power of words

The point is - words that conveyed a certain meaning were deemed important enough for a permanent association with a person (that is how naming probably developed, as either a wish for a particular type of future or an expression of some character or an event that had already taken place). In many cultures name was not assigned to a child until he performed some feat that was considered expressive of his personality. Until then everyone just called you "kid".

Today most people have a practical but a rather mundane reminder of the importance of words - a very specific kind of words - passwords. However, the idea behind passwords, viz. that words can "unlock" something hidden or secret, is millennia old.

Passwords illustrate the connection that words have to information, and by extension, knowledge. Knowledge is power.

The most practical and obvious reason why words are powerful is because they are inseparable from thought. Can you think of anything without using words in some language? It is hardly possible. Consequently, command of language is the equivalent of your ability to reason. The more nuanced your language is, - the more likely your thinking is precise, clear and versatile. Shakespeare's vocabulary was on the order of 20,000 words. On the other hand... Listen to how people talk in a crowded space, what words they use. "... and then he was like... and I was like... and they were like..." - this seemingly pervasive handicap, the utter inability to express oneself is not the problem per se, it is a symptom of a deeper issue - the degradation (or even complete atrophy) of inner mental and spiritual life.

It is hardly incidental that the three (the three-forked road or the "trivium") foundational blocks of the 7 liberal arts (Ars Liberalis) were grammar, rhetoric and dialectic (or logic). Notice the progression - from basic rules of language (writing), to the essential ability to creatively put those rules together in expressing oneself by way of public speaking, and, finally - the ability to reason. Only after mastering these essentials, an aspiring student would proceed to the more specific studies - arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy. Most powerful men in history have been men who knew how to mesmerize an audience - for good (think MLK or JFK) or evil (think Hitler, Mussolini).

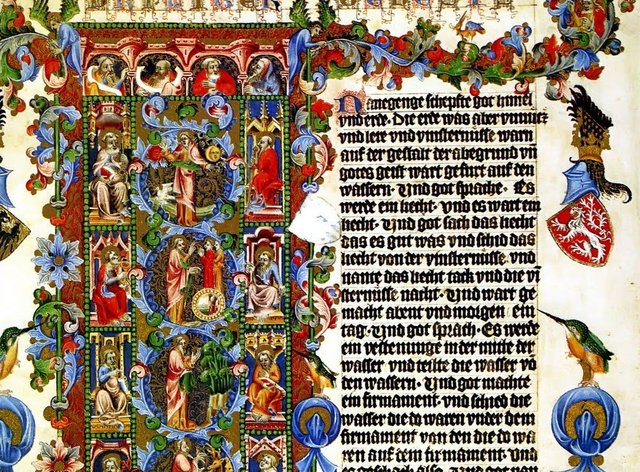

The medieval education system which ushered in the modern scientific era was hugely invested in the power of language and words.

Fragment of Wenceslas Bible c. 1389

A little background

The first time these ideas really came home for me was after reading Owen Barfield's "Poetic Diction". It is a mind-bending, if not to say mind-blowing book. In it Barfield shows how words are similar to the bones a paleontologist might dig out of the ground. As bones congeal the evidence of life that existed sometime in the past, words are the capsules of meanings that existed in the past. A closer look at a bone of an extinct animal might give us some clue about his external appearance or even some clues about his life. A closer inspection of words, on the other hand, gives us a look at something much more - a potential meaning that is ready to leap back into our lives, should we choose to let it. It is like holding a bone and having the ability to invite the pterodactyl to fly again... in your backyard.

What I would like to do with this series is to introduce a few of these largely extinct meanings and see if you catch the same excitement and breath of fresh air - winds that are blowing at us from the time of Homer and Socrates, Cicero and Horace. I am choosing Greek and Latin as my languages of choice, but almost any other ancient enough language will work as well.

Excursion #1 - "word"

The most logical place to start is with the word "word". There, I said it - "logical" - and pretty much gave it away already, because, of course, the Greek word for "word" is "logos" - λόγος. And, wonderfully, it itself shows beautifully the connections I have tried to make between word and thinking, because of course "logos" stands for both speech, word and reason. In fact, it is a hodgepodge word that has literally dozens of shades of meaning, depending on the context. And it is not surprising - words tend to have this kind of chameleon-like power to transform themselves into different things in different contexts.

One can see how from the earliest known usages of "logos" how it possessed its Protean duality. For instance, when Hesiod describes the crafty plan of Zeus to devour Athena, he uses the phrase "αἱμυλίοισι λόγοισιν" - "cunning words", but one can see how it could mean a type of reasoning or persuasion that is implied. (Hesiod, Theogony 890). On the other hand, in Homer's Iliad "logos" is used primarily in its more colloquial sense of "speech" or "words" (see the description of Patroclos' "cheering words" to Euryples in Homer, Iliad , 15.393).

Excursion #2 - "school"

This is one of those wonderful cases of words that have gradually changed their meaning, and thus possess the greatest contrast and insight when their original sense is rediscovered. Our English word "school" is immediately derivable from Latin "schola" which has the meaning of "learned debate", "lecture", "dissertation". The words "scholasticism", "scholastic" also come from the same root. This is intuitive enough. But, if we dig a bit deeper, we discover that the Romans actually borrowed this word from the Greek σχολή - "skoleh" which literally means "leisure, ease, rest". Wait, what? I thought that is what you do in between school work, not while you are at it? What gives?

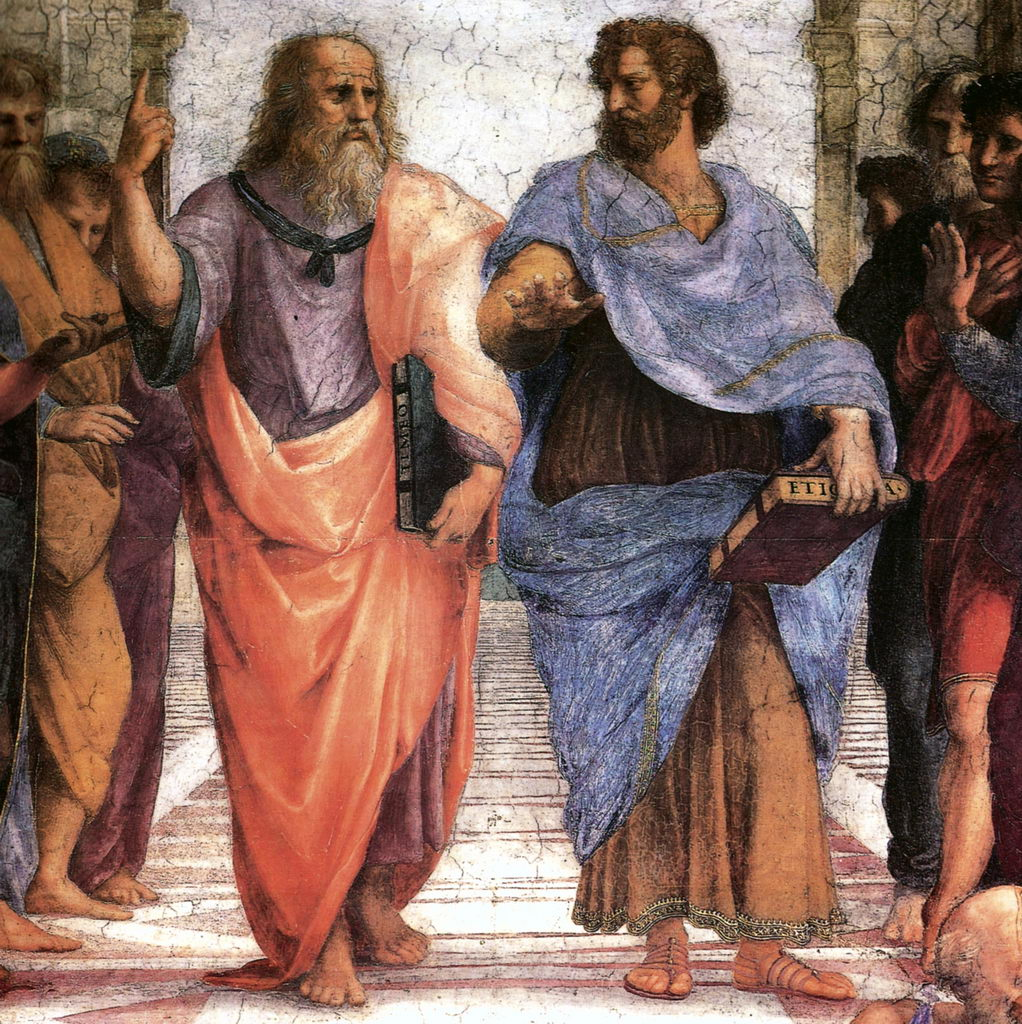

Well, the Greek idea was actually the opposite. The idea of study was closely associated with the idea of leisure (remember Plato's Symposium - the philosophers are basically having a party, reclining and havin a ball of a time, as they zero in on the definition of Love). Only those who could afford leisure, a respite from what one "had to do", were considered able to achieve the necessary tranquility of mind that would be conducive to contemplation and study of the world. It was only later that the association of "leisure" with "study" was forgotten and the former meaning was completely eclipsed by the latter.

Perhaps our idea of "school" with its over-engineered approach misses the very essence of what real study and learning is about. And we would never know about it without this little word "skoleh" which led us on this eye-opening detour.