Originally posted in Syncretic Politics June 21, 2019

Source: Forbes

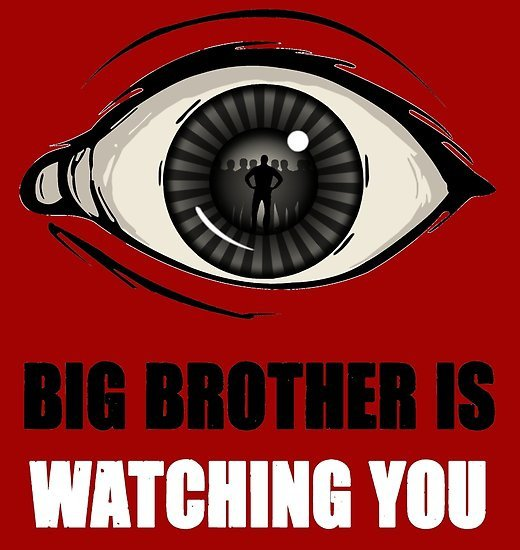

In Chicago, food trucks are not allowed within 200 feet of a food establishment, which includes not only restaurants and grocery stores, but convenience stores as well. To add insult to injury, the city also requires food truck vendors to install GPS tracking devices on their vehicles that transmits location data to a third party API every five minutes and are required to keep at least 6 months of location data. The state supreme court held that forcing businesses to install GPS tracking devices on their vehicles does not constitute a 4th amendment search because the GPS tracking device is a requirement to obtain an occupational license and food establishment permit and because the data is transmitted to a publicly accessible third party application rather than directly to city bureaucrats. However, the implications of this case go well beyond food trucks. About 20% of the labor force of Illinois needs a license to work. This would set a precedent for forcing other types of businesses to track their location in the future, some of whom may use personal vehicles to conduct business, which would directly conflict with the U.S. v. Jones ruling. Furthermore, the state supreme court contradicted themselves by simultaneously holding that forcing food trucks to operate with a GPS tracking device does not constitute a 4th amendment search and that if it did constitute a search, it would be a reasonable search because business owners have a reduced expectation of privacy and the city may have a substantial interest in enforcing the food truck ordinance. The latter confirms that the court would uphold this ordinance even if the city installed the GPS tracking devices themselves, even without the owner’s knowledge, and directly monitored their location. Remember this impacts more than just food trucks. The city could directly track vehicles used to conduct business, including personal vehicles in cases where a proprietor does not have a separate commercial vehicle, and this would be “reasonable.” For instance, if someone ran a home catering business, and used their own car to make deliveries, the government could install a GPS tracking device on their car, directly monitor their location and according to the Illinois Supreme Court this would be a perfectly “reasonable” search even though it would directly conflict with Jones and Carpenter, two U.S. Supreme court cases that established location tracking, one through cell site location data and another through GPS tracking, as a 4th amendment search.