Read Part One and Part Two.

“You are ALWAYS being assessed!”

No other words sum up Special Forces Assessment and Selection (SFAS) more for me, and I’m sure many others would agree. I found out what these words meant and just how important they would become.

The day we left the relative comfort of Special Operations Preparation and Conditioning (SOPC) for SFAS was uneventful, but I still remember it distinctly. It was an early January day that still seems distinct to North Carolina: cold, damp, rainy, and full of sandy pine trees.

There were rumors swirling after returning from Christmas leave that the December SFAS class was outside during a major ice storm (which we all slept through, since it was on a weekend).

The rumor was that a few guys almost died from trees falling on them, with a few more just generally getting lost and frozen in the woods. Inspiring.

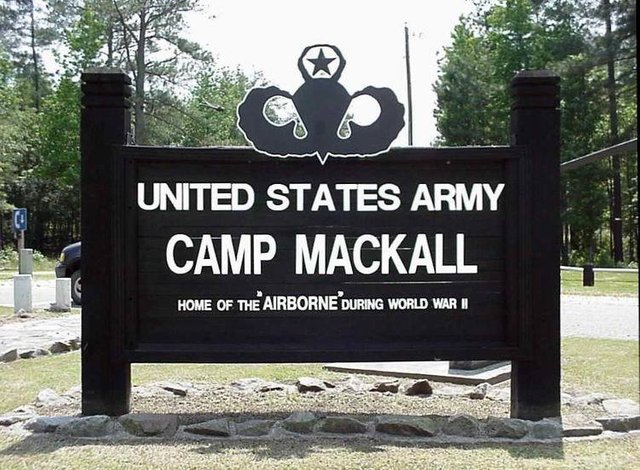

Side note: This was one 'barracks intel' rumor that actually turned out to be true. It was a miracle there were no deaths in the December 2002 SFAS, based on stories I heard. One guy managed to walk from the training area all the way back to Camp Mackall in a number of hours. The cadre had a number of rescue parties mobilized at this point, assuming the worst of this particular candidate.

I don’t think we were looking forward to the weather. We were looking forward to getting this shit over with. None of the other 18 X-Rays (Special Forces Recruit) wanted to go home, or to the 82nd Airborne for that matter. No offense against the 82nd Airborne. They have some great people over there. But it isn’t a Special Forces Group and it wasn’t why we were going to Selection.

I quite honestly don’t remember arriving. It was a total blur.

I remember downloading our gear and being told to go into the tin huts that were set up amidst a field of gravel that would be our ‘home’ for the next few weeks. The rest of the day was wholly uneventful, other than guys streaming in throughout the night, downloading trucks full of gear and bodies.

By the final count, I think our class totaled around 400 guys, all apparently ready to be ground into dirt.

SOPC definitely prepared us. We knew roughly what was coming. We had a chance to try out Nasty Nick, the infamous obstacle course at Camp Mackall. We had all completed the swim test of 25 meters in boots and uniform,

For the uninitiated, swimming in boots, utility cargo pants, blouse, and t-shirt absolutely sucks. Its like having a bunch of really weak people hanging on to your body while you're trying desperately to not drown.

We had all received some legitimate, world-class training in cross-country land navigation and had passed the barriers of those tests. We all knew that ruck marches sucked the life out of you.

Ultimately, you can never truly be 'prepared' in the truest sense of the word for something like SFAS. It’s just not something that humans typically endure or experience, willingly.

The general idea was that each day was a new event, or a new test. The cadre found it very important to remind us whenever they interacted with us (which wasn’t often, surprisingly) that we were always being assessed.

We were all assigned numbers, based on where our last names fell in the rosters. I was roster number 161. This meant that everywhere we went, we either needed to be wearing our fluorescent road guard vest with our number showing, or wearing our fatigues with white engineer tape sewn to the legs and jacket with the number written big and bold so the cadre could take notes on our every movement.

This was my actual roster number that I saved

Interestingly, the cadre weren't always watching. Actually, I don’t really remember seeing the eyes of any cadre during the daytime since they always had on sunglasses. You could never know what they saw or took note of. Nothing to indicate who their gaze was directed at.

Always. Being. Assessed.

We were told explicitly that we were not to sleep until lights-out time. Instructions would be on the whiteboard near the cadre hut. Someone from each hut (one hut = ~100 guys each) had to be checking every 5 minutes to make sure instructions weren’t missed. Most instructions only gave 15 minutes to prepare, sometimes much less. All part of the mind games, of which we were still being assessed on.

The first official day of the course came. Naturally, being the government, this consisted mostly of in-processing and paperwork. I remember sitting for what seemed like hours in one of the large classrooms within the camp, filling out the psychological evaluations and other paperwork. Candidates who fell asleep weren’t woken by the cadre. But you could see that the cadre took note on their clipboards. Generally, the buddy next to them would wake them up. I assume the cadre noted their neighbors as well for lack of situational awareness.

I must’ve been moderately delirious by the time I did the psychological evaluation. I know it was very late and we had all been up for around 18 hours at the time it was completed. A few questions I didn’t take seriously. For anyone who has taken this test, or tests like it (I believe this was the MMPI, you should know why not taking it seriously would bite me in the ass later.

As I said, each day was a new event and a new test. First was the Army Physical Fitness Test, which is comparatively trivial to the rest of the events. Two minutes of as many proper push-ups and sit-ups as you can do, followed by a two mile run. Early morning winter runs in battle-dress uniforms and tennis shoes have a way of waking you up. This is especially true when running in the loose sands of North Carolina. Fortunately, after constant training for the previous seven months, the push-ups and sit-ups routine embedded so deeply at this point for myself and the rest of the ‘SOPC kids’, it was a breeze.

Like magic, just as we had been told for weeks, the PT test would eliminate more people than you could imagine. Failure to surpass the 90th percentile in each event was rewarded with a 21-day detail of helping out the Selection Cadre. This did not sound enjoyable. The 90th percentile scores required <14:30 minute two-mile run, around 60 push-ups in two minutes, and 70 sit-ups in two minutes.

Four of the events were timed runs and ruck marches of an undefined distance. There were two separate runs and two separate rucks. Each was randomly thrown at us on different days. You are not told the distance. You are not told a standard. You are only told to be in formation in a certain uniform (with or without a rucksack and the required weight), marched to a random point, and told to follow the cones marked with directional arrows. Line up. Begin.

Watches aren’t allowed, so you can’t pace yourself. Even if you could know what time you’re running, you wouldn’t know the distance. All mental games. Without diving too deep into the theory, we were explained the purpose through prior SOPC graduates who were selected.

Consistency was what they were looking for. Weak times one day and stellar times another day shows inconsistency. The cadre would wonder why. The answer would generally never be a good one.

During one ruck march in the early morning, I remember finishing as the sun was coming up. I had never seen a pack of humans generate steam before. It was a hell of a sight to behold a bunch of huddled guys sweating their asses off, creating a giant cloud above them as they simultaneously tried to cool down and stay warm.

I received added bonus points that morning when I realized that icicles had formed from my sweat as it dripped off the brim of my patrol cap. That doesn’t happen often, but it ranks pretty high on the cool-chart, right next to having your beard or mustache freeze.

The worst day for me during the first “half” of SFAS was the rifle-and-log PT day. I got straight up broken. I don’t know how many hours it was, to be honest. Probably three or four. I mentally blocked much of that day. I remember the locations of the events and roughly what happened, so I know I was there. Anything else added would just be pure bullshit at this point. It only got more difficult from here on out, though not always physically.

You can see this day in all of its full HD glory from this documentary made by the Discovery Channel, 'Two Weeks in Hell'. This was filmed a number of years after I went through SFAS and there was no yelling that I remember. It was far more oppressive and spirit crushing.

One day was the 'Nasty Nick', named after . For those who aren’t in the know, Nasty Nick is regarded as one of the tougher obstacle courses in the United States Military. There have been more than a few pissing contests over whether the obstacle course maintained by the Ranger’s named "Darby Queen" is more difficult, but I’m all out of piss at the moment.

The rough flow of Nasty Nick goes sort of like this: rope climb, rope climb, rope climb, run, crawl through tunnel, rope climb, freeze in terror before walking down monkey bars, barbed wire crawl, rope climb, Tarzan rope swing, monkey bars, break through ice and swim through a giant puddle, cargo net, sprint.

It was much easier to type the process than to actually run through it. Plus, you don’t feel the oxygen pulled out of your lungs when you enter the giant puddle that is roughly 34 degrees. Or the icicles that form on the cargo net as a result of dripping wet candidates crawling up it.