What is life?

(comment below)

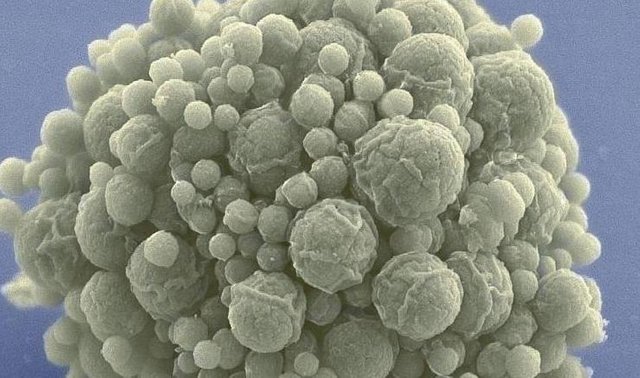

Using a technique known as global transposon mutagenesis, Dr. Clyde A. Hutchison III, professor of microbiology at the UNC-CH School of Medicine, and colleagues at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) in Rockville, Md., found that roughly a third of the genes in the disease-causing Mycoplasma genitalium were unnecessary for the bacterium's survival.

The technique -- a process of elimination -- involved randomly inserting bits of unrelated DNA into the middle of genes to disrupt their function and see if the organism thrived anyway.

Such research is a significant step forward in creating minimal, tailor-made life forms that can be further altered for such purposes as making biologically active agents for treating illness, Hutchison said. More immediately, it boosts scientists' basic understanding of the question, "What is life?"

"Cells that grow and divide after this procedure can have such disruptive insertions only in non-essential genes," he said. "Surprisingly, the minimal set of genes we found included about 100 whose function we don't yet understand. This finding calls into question the prevailing assumption that the basic molecular mechanisms underlying cellular life are understood, at least broadly."

Further work will explain those functions and create a more exact number of the minimal genes required to create life in the laboratory, the scientist said. New organisms bearing only the fewest genes needed to survive could have major commercial, social and ethical implications.

A report on the research appears in the Dec. 10 issue of the journal Science. Besides Hutchison, authors are Drs. Scott Peterson (Hutchison's former student), Steve Gill, Robin Cline, Owen White, Claire Fraser and Hamilton Smith, all of the institute, and Craig Venter, who founded TIGR and now heads Celera Genomics.

"Defining the minimal genome is a very fundamental problem, and no one else seems to be approaching it experimentally," said Nobel Prize winner Hamilton Smith, who was a TIGR investigator when the work began.

A genome is the complete set of genes, or genetic blueprints, an organism contains in each of its cells. The human genome is about 5,000 times larger than that of Mycoplasma genitalium, which causes gonorrhea-like symptoms in humans. Scientists study it in part because it contains only 517 cellular genes, the fewest known in single-celled organisms.

"The prospect of constructing minimal and new genomes does not violate any fundamental moral precepts or boundaries, but does raise questions that are essential to consider before the technology advances further," wrote Dr. Mildred K. Cho of the Stanford University Center for Biomedical Ethics and colleagues in an accompanying Science editorial.

"How does work on minimal genomes and the creation of new free-living organisms change how we frame ideas of life and our relationship to it?" Cho said. "How can the technology be used for the benefit of all, and what can be done in law and social policy to ensure that outcome?

"The temptation to demonize this fundamental research may be irresistible," she said. "However, the scientific community and the public can begin to understand what is at stake if efforts are made now to identify the nature of the science involved and to pinpoint key ethical, religious and metaphysical questions..."

Hutchison was co-inventor of a technique known as site-directed mutagenesis, which is now used by researchers around the world for introducing designed changes into genes. His friend and colleague Dr. Michael Smith of the University of British Columbia won a Nobel Prize for the work in 1993.

TIGR is non-profit research institute founded in 1992. Its researchers conduct structural, functional and comparative analyses of genomes and gene products in viruses, bacteria, other microorganisms, plants, animals and humans and has pioneered determining the sequences, or structures, of genomes.

University Of North Carolina At Chapel Hill. "Scientists Find Smallest Number Of Genes Needed For Organism's Survival." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 13 December 1999. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1999/12/991213052506.htm>.

Aside from the fascinating technical achievement this represents, it also raises the very interesting question "What is life?", not so much begging a defining description, but rather, is life something man can actually create? I believe the answer is an emphatic yes, but to defend that, I need to return to the basic definition of life.

The definition of life has been an evolving challenge that goes back to before Aristotle. Briefly, there are three major definitions that have come out of history

There's the Mechanist perspective, such as Aristotle's view of life as animation, a fundamental, irreducible property of nature, and later Descartes's view of life as a mechanism.

The Vitalists, such as physiologist J.S. Haldane, who insisted that the laws of chemistry and physics just were not robust enough to account for biology.

As science evolved we saw the Biochemical idea of life, which came out of the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Cambridge under the guidance of Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins around 1913. Here, life was seen as a byproduct of highly organized systems and processes.

In the 1940's Schrödinger, the man who gave us the Quantum Cat, published a book called "What is Life?", which had a major impact upon the work of Crick and Watson, discoverers of DNA, as it raised the idea of life being encoded on a molecular level. His work also raised the question of how order could give rise to order (i.e. heredity), breaking the 2nd law of thermodynamics.

Some researcher looked for the answer by looking into how life began in the first place, the origin, or emergence, of life. J.S. Haldane came up with the first modern hypothesis, describing geophysical conditions that might have existed in the earliest days of life on the planet.

Today, we can create artificial life and artificial intelligence, but we still can not answer the questions "What is life?"

My issue with these modern theories is they attempt to describe life as a product of materialism. They are studying and explaining the processes and systems of cells, molecules, atoms in an attempt to understand what life is. This is like studying how an oven works to understand the intentions of the chef.

On the other end of the spectrum we have the Nikola Tesla, who claimed crystals are alive when he said “In a crystal we have clear evidence of the existence of a formative life principle, and though we cannot understand the life of a crystal, it is nonetheless a living being”, although one could argue that this is simply an extreme view of the organizational principle of life.

Not being a biologist, theologist, or any 'ist' that has an opinion on the subject, I can grossly oversimplify things due to my glaring lack of knowledge... it's one of the definite advantages of ignorance.

In my view, everything that exists is alive, and it is more a question of where on the spectrum of life something exists. This is described in much greater detail in another post that is beyond the scope of this post.

This post is about the organic structures (single-celled organism) that can support self-replicating life (minimum of 265 to 350genes) and whether that constitutes the creation of life. The answer is "yes" and "no". "Yes", the creation of artificial organisms qualifies as living organisms, but "No", we are not creating life. We are creating a vessel for one form of life that can be expressed to the degree allowed by that vessel. Simple vessels, like a plastic spoon, are carriers of life, but at a level too weak to detect and in a form too unorthodox to recognize.

Ultimately, at least in my definition, life can be reduced to simply energy. If something has energy, it is alive. If something has no energy, it ceases to exist. This is based on the more abstract idea that energy itself is an expression of life, and it is the nature of energy to move, to expand, to interact whenever it can and to whatever degree is possible given the limits of its medium, be is atoms or galaxies.

I also predict (see another post) that we will soon be seeing a new form of life on the spectrum, as we have built the vessel, the processes, and systems, and supplied the energy, and once we add the intelligence of quantum computing AI, we will have opened a door behind which we have little clue what lies. I hope I live long enough to see that.