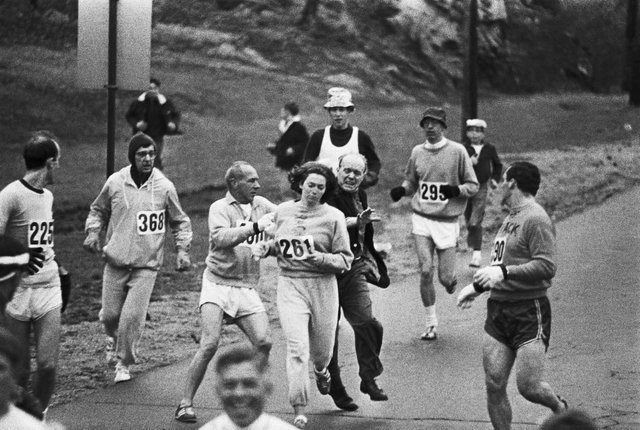

Humankind has a long history of neglecting moral concerns when it comes to safeguarding interests of specific groups. Within only the past several generations, biological discrimination has culminated in multiple events of organised genocide resulting in the extermination of millions of members of a particular race (Charny, Parsons, & Totten, 2004; Ponting, 2000).

In hindsight, many question how this was allowed to occur, and yet, little consideration is usually given to current cultural realities that reflect a continuation of much the same story. That is, whether prejudicial treatment is instead, of a religious, sexual, political, or economic orientation.

Likewise, the present relationship humans have with other forms of life on the planet is similarly bound up in patterns of immense suffering and violence (Monson, 2005; Patterson, 2002).

Although the moral sphere that encompasses human behaviour has now extended to the point where certain inalienable rights and duties are commonly recognised and accepted within the species, this process is still largely at an embryonic stage when it applies to non-human animals (hereafter "animals"). The long-standing view that scientists have the right to conduct invasive research on animals if there is some perceived future utility in doing so, rests on flawed moral premises and inaccurate underlying assumptions. Recognising this signifies profound implications for the future of animal welfare and rights, as-well as for a diverse spectrum of human endeavours, especially medicine and human health.

Reality check: The current human predicament

While progress of the latter sort is evident, such as with the 2010 European Directive on Animal-based Experiments among other regulatory changes that have either recently occurred (Gross & Tolba, 2015; Kahn, 2012) or are on the near horizon (Zurlo, 2012), there is still yet, a significant necessity for further advancement.

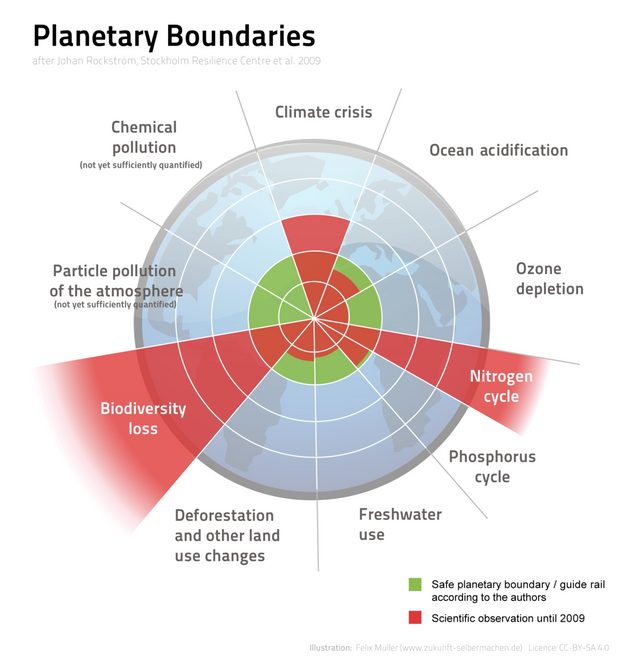

In the past 50 years, Earth has lost over half of its biodiversity (World Wildlife Fund for Nature, 2014) – the level of species extinctions being at a rate unprecedented since the demise of the dinosaurs circa 65 million years ago (Ceballos et al., 2015). Moreover, the ‘planetary boundaries’ concept, which seeks to define core “environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate” highlights a more disturbing situation (Steffen et al., 2015, p. 736). Steffen et al., (2015) note that out of the nine constraints in total delineated, four have crossed respective safe zones – these being, biosphere integrity (earlier “biodiversity loss”), biogeochemical flows, climate change, and land-system change.

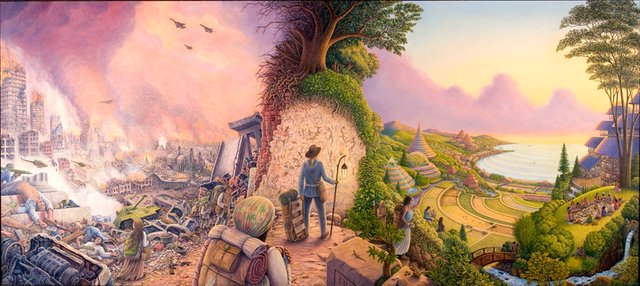

These findings suggest an ecological crisis the likes of which humankind has never experienced before. It also challenges commonly perceived notions of homo sapiens (Latin for "wise man"), as an intelligent and superior species – far above in worth than other forms of life on Earth.

This view of self-importance might account for why humans feel justified in slaughtering over 56 billion land animals a year globally for consumption (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2015), and conducting invasive research on over 115 million animals a year globally (Peggs, 2015). Whatever the underlying basis, the claim has been advanced comparing the Nazi holocaust with the ongoing treatment of animals by humans (Patterson, 2002). It should, therefore, be clear that humanity faces grand challenges that require an evolutionary leap in consciousness; in many ways, a fundamental re-contextualising of our relationship with nature and all other forms of life on the planet.

An overview of the dominant ethical approaches and positions

At the heart of the ethical division within invasive animal research, stand two polarising forces operating from radically different principles of concern. The dominant approaches of utilitarianism and deontology, which have been arrived at over the past several decades of debate, both currently hold normative status as the ideal starting point for continued progress.

To briefly explain them, utilitarianism, which is a form of consequentialism, determines the morality of an action by the results producing the most overall well-being. This involves a weighing of the known harms to animals versus the potential benefits. Thus, the utility factor of invasive animal research must at least lead to relevant, scientifically-verifiable information that enhances human understandings and which cannot be reasonably ascertained via other means (Carbone, 2012). Deontology, or the rights position, determines the morality of an action by its adherence to a set of consistent principles, laws, or social standards. From this view, animals are seen to have an inherent value, as a result of being subjects of a life who possess morally important characteristics. This ultimately means that animals should not, for any reason or set of reasons, be reduced to an instrument – a means to an end (Regan, 2004). It is reasonable to view utilitarianism and deontology as respectively, collectivist and individualistic in nature (Ryder, 2009).

Other ethical approaches of lesser importance include anthropocentrism, contractarianism, the convergence position, and the principle of the three R's (replacing, reducing, and refining the use of animals in scientific research) (Gross & Tolba, 2015).

Although utilitarianism as an ethical position is compelling in some respects, examining the built in presuppositions it entails is necessary in order to better gauge the strength of its approach.

Failures of the utilitarian argument in support of invasive animal-based research

Significant contention exists within the scientific community as to the effectiveness of invasive animal research in positively advancing human understandings (Gilbert, 2012). This is despite pre-eminence of animal-based research as the "default and gold standard of preclinical testing" (Akhtar, 2015), and all but two of the Nobel Prizes in Medicine over the past 100 years having been dependent upon animal-based research (Redmond, 2012).

Today, many scientists still maintain that animal-based research is vitally important in serving human interests, such as in using monkeys to understand and cure Parkinson disease (Redmond, 2012), however, there are strong grounds for challenging this position. From an ethical perspective, the utility factor of animal-based research is predominantly, if not entirely, oriented towards human benefit (Rollin, 2012). Consequently, there is an assumption of human superiority on which invasive animal research rests, that may be speciesist in nature. The term "speciesism" was introduced by psychologist and philosopher Richard D. Ryder in 1970, to denote prejudicial behaviour in favour of one species over another (Ryder, 2009). Thus, the utilitarian argument in support of invasive animal research is discriminatory, unless an objective metric for classifying a species worth is formulated, and humans rate highly. If the mark of a successful species (as is believed to be the case by this author) is determined by how well it lives in balance with all of nature, humans at the present time do not appear to rate well.

In relation to health and medicine generally, significant biological differences exist between humans and other animals which results in research findings that lack reproducible value (Akhtar, 2015). Evidence of successful translation of data from animal-based research to humans has been shown to be seriously lacking in medical conditions as diverse as Alzheimer's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cancer, HIV/ AIDS, spinal cord injury, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (Akhtar, 2015). In addition, highlighting the misleading nature of animal-based research, drugs such as aspirin and penicillin that have been safely used by humans for decades, may not have been available today if preclinical studies were subjected to current practices involving animals (Akhtar, 2015). Animal-based research, therefore, may be inferior to human-based procedures and technologies, to the degree it does not encounter the same problems of congruence inherent in the translation of data from animal-based research to humans.

Another factor that can further compromise the legitimacy of the use of animals for biomedical research, is the influence of financial profits inherent to the industry (Peggs, 2015). Vested interests on the part of suppliers of animals and related specialist equipment (such as cages, restraints, and guillotines) as-well as regulatory agencies, derive significant economic incentives which in some cases amount to billions of dollars (Peggs, 2015). This potential bias represents a risk factor for corruption, most particularly in shaping public policy. However, the extent this applies to less directly involved parties, such as drug or pharmaceutical companies, is not entirely clear. If individuals and businesses within the Market are disposed to choose the most cost-effective avenue for research and development over time, why is animal-based research still occurring to such a large extent? To account for the reasons, more research needs to be done to assess the impact of specific legal, cultural, and economic barriers that may hinder change. Consequently, while it is difficult to assert categorically that animal-based research is in-efficacious, there is still considerable evidence and reasoning to support an extensive shift towards human-based procedures and technologies.

Towards a non-speciesist and predominantly deontological conception of animal welfare and rights

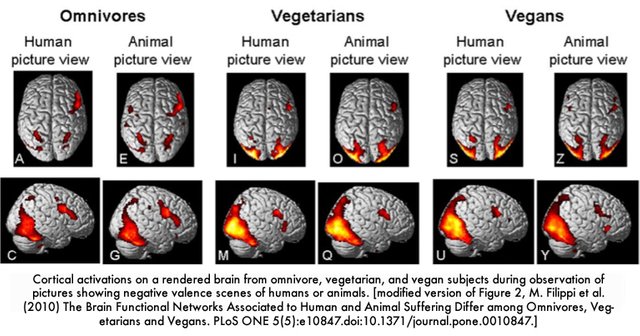

It may be paradoxical, but there is a core utilitarian argument in favour of a non-speciesist and predominantly deontological conception of animal welfare and rights. By fostering kindness and respect towards other animals, members of the human species may be more inclined to treat each other better (Filippi et al., 2010).

Indeed, speciesism has been suggested to be at the root of other forms of discrimination like racism, sexism, or classism (Tuttle, 2004). This means human rights may be inextricably linked to animal rights, requiring the proper relationship between the two to be realised. The degree to which humans value 1) fostering kind and respectful relationships, 2) ending varied forms of discrimination, and 3) advancing human rights, versus the perceived benefits obtained from animal-based research, is the utilitarian equation to resolve. Although, it is the opinion of this author that given the current state of the planet, humans have a moral obligation on both deontological and utilitarian grounds, to stop treating other animals as mere objects or property.

All forms of animal exploitation should be abolished, whether it is in laboratories, factory farms, or in the wild.

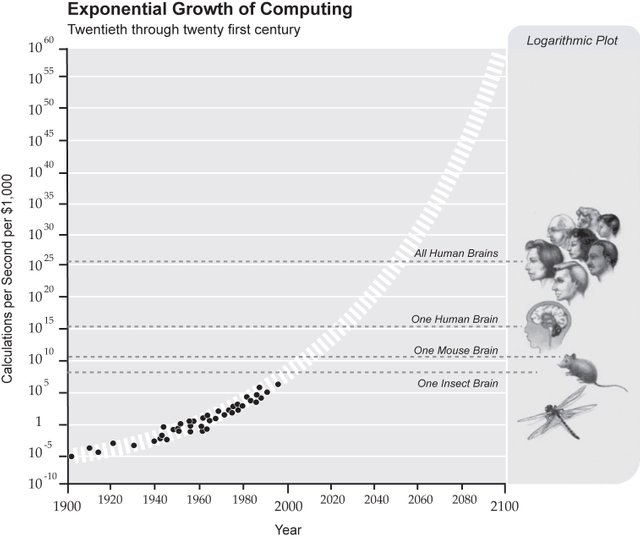

An important point to make here, is that a moral ideal is separate from issues of practicality – difficulties encountered are secondary to the ethical responsibility that remains. That said, while transitioning away from invasive animal research might seem like a difficult or even impossible task, such a reality is actually more possible than many may think.The pace of technological change in society is theorized to be increasing exponentially.

Possibilities related to nanotechnology, additive manufacturing, artificial intelligence, robotics, biotechnology, and computer science have the potential to radically transform every aspect of ourselves and society (Kurzweil, 2005). What this ultimately means for knowledge production can only be speculated at this point, but it is likely newer methodologies will supersede whatever reliability and predictive value is currently derived from animal-based research. Toxicity testing is currently undergoing a paradigm shift in this regard, with gradual phasing out of animal-based research towards such human-based procedures and technologies as cellular testing and population based studies (Zurlo, 2012).

Even food may soon undergo a revolution, with lab-cultured, artificial meat promising increased nutrition, reduced environmental costs, and no animal victims (Sharma, Thind, & Kaur, 2015).

Conclusion

Thinking more deeply about history and the current human impact on the lives of animals is necessary in order to construct a stronger ethical theory on animal welfare and rights. With the grand challenges humanity faces, calling into question the triumphant narrative of human superiority helps to provides a more accurate context for evaluating ethical claims justifying the use of animals. The key ethical theories of deontology and utilitarianism offer the most compelling arguments for how humans should interact with animals when it comes to invasive research. Although, there are significant grounds to dismiss many claims of the latter, which rests on poor foundations of moral and scientific justification. Therefore, movement towards establishing human-based procedures and technologies for research should be supported, as should an expanded moral sphere that unconditionally embraces all life on the planet, irrespective of utility to humans – doing so may potentially be the best way to advance key utilitarian goals that benefit the human species.

Developing scientific alternatives to invasive animal research and expanding the moral sphere of protection to encompass all animals irrespective of utility, may prove to increase awareness of the value of human life, as-well as ultimately offer a more effective approach to advancing human health.

Animals should no longer have to suffer the violation of their rights to live free and without harm from humans. The tree of knowledge can be climbed without falling to such lows.

Hello @mkfylfot,

Congratulations! Your post has been chosen by the communities of SteemTrail as one of our top picks today.

Also, as a selection for being a top pick today, you have been awarded a TRAIL token for your participation on our innovative platform...STEEM.

Please visit SteemTrail to get instructions on how to claim your TRAIL token today.

If you wish to not receive comments from SteemTrail, please reply with "Stop" to opt out.

Happy TRAIL!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi @mkfylfot, I just stopped back to let you know your post was one of my favourite reads yesterday and I included it in my Steemit Ramble. You can read what I wrote about your post here.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @mkfylfot! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit