The leaves had fallen, but there had as yet been no snow. I was walking through the woods along the Oka. There was not a sound in the oak and aspen groves save the chirping of the titmice and a rustling underfoot. A stone tossed into a small pool did not splash, but rolled, and the frozen water responded with a clear-sounding tuk-tuk-tuk. The ice was still too thin to support me. I pressed my heel onto it and a watery spot appeared. The sounds made by a chunk of frozen earth, a dry stick and a bit of iron dropped onto the new ice were very different, but equally pleasing. I crouched down amidst the brittle yellow grass and began tossing everything that came to hand onto the ice like a child.

Then I discerned a dull, monotonous clanging, uncommon to the woods.Someone was hitting iron with iron not far away. I decided the person was repairing a car or a wagon and headed towards the sound. The woods ended unexpectedly. A small village of about fifteen houses came into view in the clearing, and I turned towards it with the curiosity any new place arouses. There was no road in sight. In fact, there was no street, just a row of old hewn log cabins leading from the edge of the woods to the red brick church on the hill. Each house had a front garden. The well, made of dark logs, stood under the willows on a grassy patch. Time-worn paths led from each house to the well.

A huge white rock was set outside one of the houses. A man in a sweater and fur hat was sitting on the porch. As I near-ed the porch he ground out his butt, picked up a hammer and chisel, went down to the rock and the clanging that had led me out of the woods was resumed.

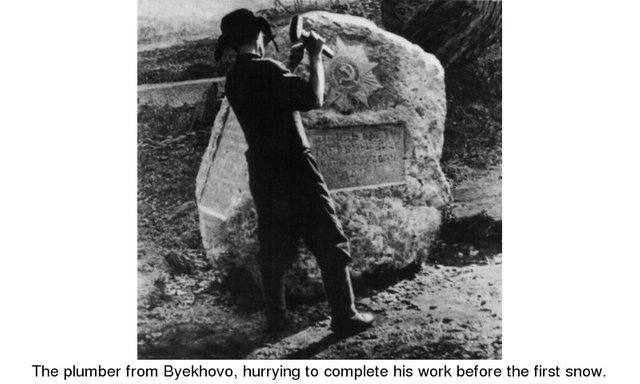

The man was cutting the rock. The emblem and lettering on the white mound were the result of many days' labors and were expertly done. A sculptor had probably come here to live in the quiet of the countryside. His small reddish beard seemed to corroborate my guess. However, I learned that the sculptor was a stoker and plumber at the nearby resort, that he had been born and raised in this village and had never had any instruction in stone-cutting but, having become interested in it of his own accord, had tried his hand at it, since there were so many big rocks along the banks of the Oka and they were all soft enough to work.

The sculptor's name was Fyodor Kurzhukov. He was completely engrossed in his work, and his small beard was obviously not for show, since his inflamed eyes and drawn features and the mass of stone chips his boots had ground into the soil all testified to the fact that he had been pounding at this rock for a long time without respite.

Fyodor Kurzhukov was working on a monument to the men killed in action on the Oka River in November 1941. "It was like this," he said. "They were going to order a what-do-you-call-it... a memorial plaque. But I said we could get a big white rock from the Oka, and that Td cut whatever had to be put on it. Here it is. It's the best I can do."

His tools were laid out on the porch, all manner and sizes of hammers and chisels. Next to these crude iron tools lay a small Order of the Patriotic War. The golden rays surrounding the red star gleamed from being often held in the sculptor's stone-powdered fingers.

"Is this decoration yours?"

"No, I borrowed it from my neighbor."

The medal was repeated in every detail on the face of the rock. Kurzhukov would take a step or two back to get a better view and then, taking up his stand, would again resume his work, sending up new sprays of white dust from the rock. The lettering on it read: "The enemy was stopped here. October-November 1941."

We sat down on the porch for a smoke. Fyodor stretched and plucked a handful of rowanberries from a tree, tossing them into his mouth one by one, his face thoughtful. Birds had pecked holes in some of the red berries. These he threw away. They fell as drops of blood on the white stone chips.

"Were the losses great?"

"Not here. Four people were killed near our village. Two mortar men, a political instructor and a boy."

He was going to cut their names on the side of the rock.

"The mortar men were Kudryavtsev and Chashkin, and the political instructor's name was Tarasov. The boy was Volodya Kuzmin. He was from our village. His mother's still alive. You can go over and talk to her if you want to. See that house at the other end of the field?"

Praskovya Ivanovna Kuzmina was not in. Her neighbor pointed to another cottage, saying she was probably caring for a little girl there.

They were playing on the floor of the small room, surrounded by toys. One was a child of about four, the other a woman of about sixty. Praskovya Ivanovna was baby-sitting for a young couple that worked at the nearby resort.

"She's just like my own granddaughter. Aren't you, Olya?"

Olya pressed close to the old woman and chewed on a rubber monkey's ear as she stared at me.

"They pay me, you know, but even if they didn't, I'd look after her. She's just like my own, aren't you, Olya?" The old woman touched her eyes with the collar of her blouse. "What can I tell you about Volodya? He was just a boy when he was killed. Just a boy. The very first year of the war. The Germans got as far as the Oka then."

While Olya had her lunch and then, growing bolder, brought me her toys, I learned about another small episode of the war and the loss of one human life. The story can be told in ringing phrases. It can be told simply, as the mother told it to me.

Volodya was a boy like any other boy. He would run off to talk to the soldiers in the trenches nearby and took kettles of boiling water for tea to the sentries.

"The river was between our boys and the Germans. There wasn't much shooting, but our boys were getting ready for a German advance. They borrowed my frying-pan to fry some potatoes. I'll never forgive myself for sending Volodya for the pan that day. I told him to get it and come right back and down into the cellar. But instead, they brought him home that evening..."

She was told that a young lieutenant had been about to go on a scouting mission but could not find a rowboat. Volodya knew where the boats were hidden, and he knew all the paths as well. Perhaps that is why the lieutenant agreed to take the boy along as a guide. They headed across the river at nightfall, but the Germans spotted them all the same. Volodya was the only one who was killed in the skirmish.

"The lieutenant wept. He kissed my hands and kept saying, 'I wish they'd have got me instead, Mother.' Volodya was given a military burial. The Red Army soldiers raised their rifles and they all fired at once. And their commander said: Tour son would have been a fine man, Mother, but the war has taken him away. We won't all return home, either. We've already come this far, as far as the Oka. And nobody knows where his life will end. But there'll be a monument to your boy one day, Mother, because your son was a hero. I hope to God all my men will be as brave as he was.' That's what he said: 4 hope to God.' I knew he was saying all that to comfort me. At first, I couldn't hold back my tears, but then I just turned to stone. When they all fired their guns over his grave the Germans started shooting, too."

Praskovya Ivanovna had not yet seen the white rock monument.

"I've heard about it. But I was afraid I wouldn't be able to walk that far. I've got rheumatism."

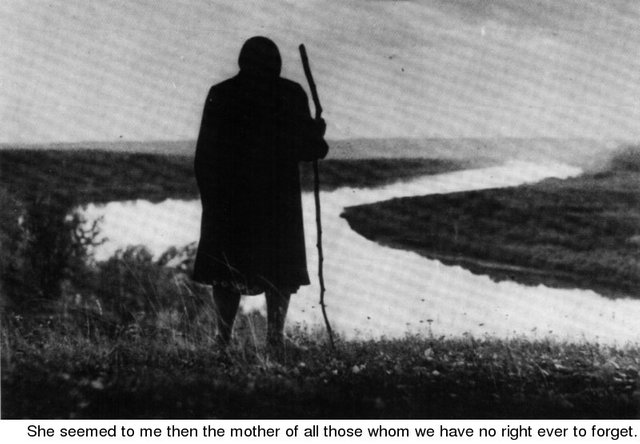

I said I would take her there. We went beyond the field, then followed the path along the edge of the woods. She crossed herself as she stood by the rock, then read the words and ran her hand over it. We walked in silence to the top of the hill over the Oka. As she leaned on her stick she spoke, as if talking to herself:

"That's the bend they were heading for. It's just the same."

There was nothing I could say. I walked off a bit and watched her as she stood there, unmoving, for such a long time. The Oka was calm and bright below, and the blue distance was endless. Standing over the vast expanses, this lonely woman seemed to me the mother of all those whom we have no right ever to forget.

This was on a Sunday in November, when the woods along the Oka were awaiting the first snow. I walked down a now-familiar path from the village of Bekhovo and came to a stop once again by the frozen pool. I had several white chips in my pocket and tossed them onto the ice. Once again I wondered at the clear-sounding tuk-tuk-tuk. It was amazingly still in the forest save for the same dull clanging I had heard that morning. It was the plumber from Byekhovo Village, Fyodor Kurzhukov, hurrying to complete his work before the first snow.