It is a good question, but I was a little surprised to see it as the title of a research paper in a medical journal: “How Happy Is Too Happy?”

Yet there it was in a publication from 2012. The article was written by two Germans and an American, and they were grappling with the issue of how we should deal with the possibility of manipulating people’s moods and feeling of happiness through brain stimulation. If you have direct access to the reward system and can turn the feeling of euphoria up or down, who decides what the level should be? The doctors or the person whose brain is on the line?

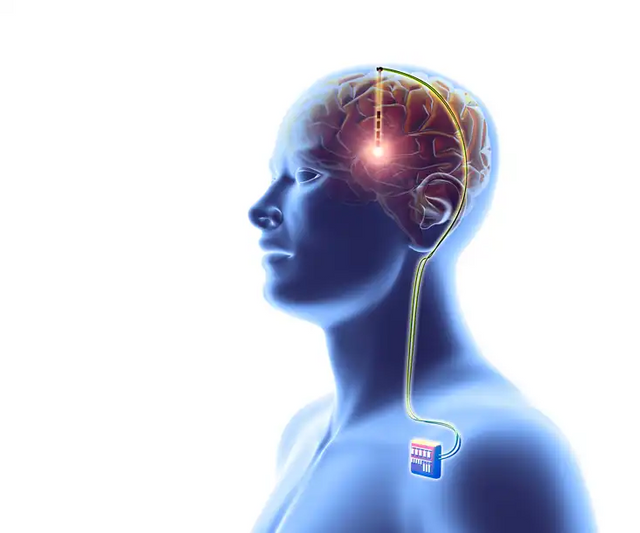

The authors were asking this question because of a patient who wanted to decide the matter for himself: a 33-year-old German man who had been suffering for many years from severe obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety syndrome. A few years earlier, the doctors had implanted electrodes in a central part of his reward system—namely, the nucleus accumbens. The stimulation had worked rather well on his symptoms, but now it was time to change the stimulator battery. This demanded a small surgical procedure since the stimulator was nestled under the skin just below the clavicle. The bulge in the shape of a small rounded Zippo lighter with the top off had to be opened. The patient went to the emergency room at a hospital in Tübingen to get everything fixed. There, they called in a neurologist named Matthis Synofzik to set the stimulator in a way that optimized its parameters. The two worked keenly on the task, and Synofzik experimented with settings from 1 to 5 volts. At each setting, he asked the patient to describe his feeling of well-being, his anxiety level, and his feeling of inner tension. The patient replied on a scale from 1 to 10.

The two began with a single volt. Not much happened. The patient’s well-being or “happiness level” was around 2, while his anxiety was up at 8. With a single volt more, the happiness level crawled up to 3, and his anxiety fell to 6. That was better but still nothing to write home about. At 4 volts, on the other hand, the picture was entirely different. The patient now described a feeling of happiness all the way up to the maximum of 10 and a total absence of anxiety.

“It’s like being high on drugs,” he told Synofzik, and a huge smile suddenly spread across his face, where before there had been a hangdog look. The neurologist turned up the voltage one more notch for the sake of the experiment, but at 5 volts the patient said that the feeling was “fantastic but a bit too much.” He had a feeling of ecstasy that was almost out of control, which made his sense of anxiety shoot up to 7.

The two agreed to set the stimulator at 3 volts. This seemed to be an acceptable compromise in which the patient was pretty much at the “normal” level with respect to both happiness and anxiety. At the same time, it was a voltage that would not exhaust the $5,000 battery too quickly. All well and good.

“It’s not my job as a neurologist to make people happy.”

But the next day when the patient was to be discharged, he went to Synofzik and asked whether they might not turn the voltage up anyway before he went home. He felt fine, but he also felt that he needed to be a “little happier” in the weeks to come.

The neurologist refused. He gave the patient a little lecture on why it might not be healthy to walk around in a state of permanent rapture. There were indications that a person should leave room for natural mood swings both ways. The positive events you encounter should be able to be experienced as such. The patient finally gave in and went home in his median state with an agreement to return for regular checkups.

“It is clear that doctors are not obligated to set parameters beyond established therapeutic levels just because the patient wants it,” Synofzik and his two colleagues wrote in their article. After all, patients “don’t decide how to calibrate a heart pacemaker.”

That’s true, but there is a difference. Few laymen understand how to regulate heartbeat, but everyone is an expert on his or her own disposition. Why not allow patients to set their own moods to suit their own circumstances and desires?

Yeah, well, the three researchers reflected, it may well come to that—sometime in the future, that is—people will demand deep brain stimulation purely as a means for mental improvement.

They stressed that there is nothing necessarily unethical about raising your level of happiness this way. The problem is the lack of evidence that it is beneficial to the individual—particularly in light of the considerable cost of the treatment. Even before battery changes, which are needed every three to five years, and regular adjustments, we are talking $20,000 for the system itself and another $50,000 to $100,000 for the operation and hospital procedures.

Today, we have to ask ourselves where a “therapeutic level of happiness” might lie and whether there are risks and disadvantages connected with higher levels.

It seems the unknown young man with accumbens electrodes didn’t buy the argument because, after a short time, he stopped coming in for checkups and vanished without a trace. Maybe he found another doctor who was willing to make him happy.

Questions of pleasure and desire go right to the core of what being a human in the world is all about. The ability to stimulate selected functional circuits in the brain purposefully and precisely raises some fundamental questions for us.

What is happiness? What is a good life?

Hedonia. There is something about this word. It rolls across the tongue like walking on a red carpet and leaves a pleasant sensation behind. Hedonia might well have been the name of the Garden of Eden before the serpent made its malicious offer of wisdom and insight. And more than anything else, hedonism has become the watchword for how we should live.

The absence of joy and pleasure—anhedonia—has, in its way, become a popular issue in the wake of the disease depression. A quarter of us are affected by it over the course of a lifetime, various studies suggest, and its frequency is increasing in the industrialized world. The treatment of depression has become both a window display and a battleground for deep brain stimulation.

As soon as the electricity disappeared, the patient reported that her sense of springtime had vanished.

It was with the American neurologist Helen Mayberg and the Canadian surgeon Andres Lozano that the method got its breakthrough in psychiatry. It struck a sweet spot in the media when, in 2005, the two published the first study of deep brain stimulation for the treatment of severe chronic depression—the kind of depression, mind you, that does not respond to anything—not medicine, not combinations of medicine and psychotherapy, not electric shock. Yet suddenly, there were six patients on whom everyone had given up who got better.

At once, Helen Mayberg became a star and was introduced at conferences as “the woman who revived psychosurgery.” Later, others jumped on the bandwagon, and now they are fighting about exactly where in the brain depressed patients should be stimulated. It is not just a skirmish between large egos but a feud about what depression really is. Is it at its core a psychic pain or, rather, an inability to feel pleasure?

“It’s not my job as a neurologist to make people happy.”

Helen Mayberg let her statement hang in the air between us before she continued.

“I liberate my patients from pain and counteract the progress of disease. I pull them up out of a hole and bring them from minus 10 to 0, but from there the responsibility is their own. They wake up to their own lives and to the question: Who am I?”

Helen Mayberg’s office spread out along the glass gable of a building at Emory University. Physically, there was something elfin about her with her brown pageboy hair, which rested on the edges of a large pair of spectacles. She was a striking, diminutive figure. But she loomed large as soon as she began to speak. Her voice was deep and intense, and she let her words flow in a gentle stream that forever meandered in different directions.

“We had a hypothesis, we set up an experiment, we laid out the data, and now we have a method that works for a great many patients.” She took a breath and lowered her voice half a tone. “But for me, it has always been about understanding depression.”

Mayberg began her journey into the mechanisms of depression back in the 1980s—in a time when everything was all about biochemistry and transmitters. The brain was a chemical soup, and psychological symptoms were a question of “chemical imbalances.” Schizophrenia was an imbalance in the dopamine system, and the serotonin hypothesis for depression was predominant. It claimed that this oppressive illness must be due to low levels of serotonin. The hypothesis was supported by the fact that certain antidepression medications increased the level of serotonin in the brain, but the theory did not have much else to back it up.

Then something happened to change the focus. There was a breakthrough in scanning techniques, and this meant, among other things, that you could look at the activity in living brains and compare what happened inside people with different conditions. During the 1990s, Mayberg began hunting for the circuits and networks on which depression played. Others were working in the same direction, and different groups could point out that there was something wrong in the limbic system as well as the prefrontal cortex. That is, both the emotional and the cognitive regions of the brain were involved. MRI scans of people suffering from depression revealed that certain areas were too active while others were too sluggish in relation to the normal, non-depressed control subjects with whom they were compared.

Soon, Mayberg focused on a little area of the cerebral cortex with a gnarly name, the area subgenualis or Brodmann area 25. It is the size of the outermost joint of an index finger, located near the base of the brain almost exactly behind the eye sockets. Here, it is connected to not only other parts of the cortex but to areas all over the brain—specifically, parts of the reward system and of the limbic system. That system is a collection of structures surrounding the thalamus encompassing such major players as the amygdala and the hippocampus and often referred to as the “emotional brain.” All in all they are brain regions involved with our motivation, our experience of fear, our learning abilities and memory, libido, regulation of sleep, appetite—everything that is a affected when you are clinically depressed.

“Area twenty-five proved to be smaller in depressed patients,” Mayberg relates, adding that it also looked as though it were hyperactive. “At any rate, we could see that a treatment that worked for the depression also diminishes activity in area twenty-five.”

Desire pushes all the other systems and makes it possible to have motivated behavior and to work toward a goal.

At the same time, it was an area of the brain that we all activated when we thought of something sad, and the feeling that area 25 was a sort of “depression central” grew and grew as the studies multiplied. Mayberg was convinced that this must be the key—not just for understanding depression but also for treating those for whom nothing else worked. This small, tough core of patients who had not only fallen into a deep, black pit but were incapable of getting out again. These were the chronically ill for whom nothing helped, the kind of depressive patients who often wound up taking their own lives; it was this type of patient that, 50 years ago, were warehoused in state hospitals.

If only Mayberg could reach into their area 25!

And she could, with the help of a surgeon. Around the turn of the millennium, when she arrived at the University of Toronto, she met one of the institution’s big stars, Andres Lozano. He had not only done deep brain stimulation on several hundred Parkinson’s patients but was known as a researcher who was willing to take risks, who was eager to explore new territory. Here was something radical, and Lozano was more than intrigued. So it was simply a matter of recruiting patients. Over several months, the two partners spread the word, gave countless lectures to skeptical psychiatrists and, finally, began to get patients referred to them. One of them, a woman who had worked as a nurse before she became ill, was the first to sign up for the project. She had tried it all and did not expect an electrode to change anything. But why not give it a shot?

The operating theater was booked for May 13, 2003, and everything was made ready for the big test of Mayberg’s hypothesis as well as her scientific narcissism.

“I felt the schism between my own curiosity and the patient,” she said, holding both hands out from her body. “If something went wrong, it would be because I had asked a surgeon to do something on the basis of an idea.”

But the surgeon patted her on the back and said that she, Helen, knew more about depression than anyone on the planet. Lozano himself was not the least bit in doubt that he could place the electrode in their patient’s brain under very safe protocols.

“Ask yourself,” he said to me, “if this were your sister, would you do it?”

Mayberg would, and they went ahead. The operation itself went by the book. The patient was told that there were no particular expectations.

“Nobody knew what would happen. So the patient was instructed to tell me absolutely everything she observed. Whether it seemed relevant to her or not.”

The team began with their lowest-placed contact and 9 volts. Nothing happened. They turned up the voltage but still nothing happened. Then they went on to the next contact a half millimeter higher in the tissue. Even though they were only at 6 volts, the patient suddenly spoke. Were they doing something to her right then? she asked.

“Why do you think that? Tell me what you are feeling.”

“A sudden feeling of great, great calm.”

“What do you mean, calm?”

“It’s hard to describe, like describing the difference between a smile and laughter. I suddenly sensed a sort of lift. I feel lighter. Like when it’s been winter, and you have just had enough of the cold, and you go outside and discover the first little shoots and know that spring is finally coming.”

Then, the electrode was turned off. And as soon as the electricity disappeared, the patient reported that her sense of springtime had vanished.

Now, years later, Mayberg pulled up her knitted sleeve and held her forearm out to me. She still got goose bumps when she talked about that first time. And when I asked about how she felt there in the operating room, she did not hesitate to admit that she was close to tears.

“There was a purity to the moment.”

Later, it became clear that the reaction was not unique—other patients got the same “lift.” For one, it was as if a dust cloud around her had disappeared, while another suddenly felt there were more colors and more light in the room. Once they had experienced this immediate effect, there was a good chance that their depressive symptoms would decrease over the first months after the operation. But the lasting effect came gradually, and it had nothing to do with euphoria or happiness.

“The patients are aware I have not given them anything but have removed something that was bothering them,” said Mayberg. She liked analogies and offered me one. “It is like having one foot on the accelerator and one foot on the brake at the same time and, then, lifting your foot off the brake. Now, you can move.”

This was the core of the Emory group’s view of depression. They did not see it as a lack of anything positive—pleasure and joy—but as an active negative process. Neither did they believe you could just “inject positive” into a patient. Rather, you have to remove the constantly grinding negative activity.

When Mayberg’s landmark paper was published in Neuron in 2005 and she gave interviews to the major newspapers, the blogosphere exploded with indignant scribblings. Doctors had crossed the line! This was the return of the lobotomy!

“The conflict arises every time science reaches a new frontier. And as soon as research has anything to do with the brain, there are people who get nervous that it can be used for enhancement.”

That was my cue. I wanted to hear what Mayberg thought about joy, pleasure—hedonia. I know some groups treat depression by stimulating areas in the reward system and “injecting positive,” as she somewhat mockingly calls it. This applied, in particular, to a duo from the University of Bonn—psychiatrist Thomas Schläpfer and surgeon Volker Coenen, who virtually churn out studies reporting impressive results.

A certain tension appeared in the room. Mayberg stressed several times that Schläpfer was a “friend and a colleague,” but she also believed that he was in a strange competition with her. That it was as if he could not deal with the fact that she came first.

The treatment of depression has become both a window display and a battleground for deep brain stimulation.

“There may be plenty of people who suffer from anhedonia and who might get quite a lot out of having an electrode placed in their reward system. But if you don’t have psychological pain, I don’t believe it’s depression. If life just isn’t good enough, it won’t do anything for you to tone down area 25.”

Mayberg related the story of a patient to me. This woman had an alcohol problem in the past and, after she had her electrodes installed, she went home and waited for them to give her a sense of intoxication or euphoria. She was completely paralyzed by her expectations, and Mayberg had to explain that there was nothing to wait for. The procedure had simply awakened the lady to the realities of her life. The symptoms of her disease were diminished, but she herself had to put something in their place if she wanted to will her life.

“Our nervous system is set up to want more and to go beyond the boundaries we run into. You don’t want just one pair of shoes, right? I fundamentally believe that you go into people’s brains in order to repair something that is broken, but there is something strangely naïve about wanting to stimulate the brain’s reward system. Ask any expert on addiction. You will wind up with people who demand more and more current.”

I asked Schläpfer about the innermost nature of depression. What did he and Coenen think about Helen Mayberg’s ideas about psychological pain needing to be extinguished, as opposed to countering anhedonia?

The big man sighed, paused for a moment, and answered by way of an anecdote from when he was studying at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. On one of the regular hospital rounds, the old head of psychiatry at the university pointed at him and asked him to name the symptoms of depression. The dutiful Swiss student stood up straight and began to recite the nine symptoms from the textbook, when the old man interrupted.

“No, no, young Schläpfer. There is only one symptom, and it has to do with pleasure. Ask the patient what gives him pleasure, and he will tell you: nothing.”

Young Schläpfer thought about his superior’s remark and actually began to ask his patients questions. He still does. Today, he believes that anhedonia is the central symptom while everything else, including psychological pain, is something that comes in addition to that. It is only when their anhedonia abates that people suffering from depression feel better. And this is not strange, because desire and enjoyment are driving engines and a key to many of our cognitive processes. Desire pushes, so to speak, all the other systems and even makes it possible to have motivated behavior and to work toward a goal.

“I am familiar with Helen’s attitude toward the reward system,” said Schläpfer with his slow diction. “But I would like to stress that we have never seen hypomania in the patients we stimulate in the medial forebrain bundle. If we overstimulate and turn the current up too high, the worst reaction we have seen is that people get a tingling sensation as if they’d had too much coffee.”

My curiosity was piqued by what Mayberg had said about the reward system and addiction. I dove into the literature and found an article from 1986, which described a case of dependence on deep brain stimulation. The journal Pain had a so-called case history of a middle-aged American woman. In order to relieve insufferable chronic pain, she had a single electrode placed in a part of her thalamus on the right side. She was also given a self-stimulator, which she could use when the pain was too bad. She could even regulate the parameters of the current. She quickly discovered that there was something erotic about the stimulation, and it turned out that it was really good when she turned it up almost to full power and continued to push on her little button again and again.

In fact, it felt so good that the woman ignored all other discomforts. Several times, she developed atrial fibrillations due to the exaggerated stimulation, and over the next two years for all intents and purposes her life went to the dogs. Her husband and children did not interest her at all, and she often ignored personal needs and hygiene in favor of whole days spent on electrical self-stimulation. Finally, her family pressured her to seek help. At the local hospital, they ascertained, among other things, that the woman had developed an open sore on the finger she always used to adjust the current.

When deep brain stimulation is no longer experimental but an approved standard treatment, anyone can take their stimulator and pay a visit to a doctor willing to set it right where they want it. Hypomania be damned.

Lone Frank is the author of two previous books in English, My Beautiful Genome and Mindfield (Oneworld, 2009). She has also been a presenter and coproducer of several TV documentaries and is currently working on a feature-length documentary about heath and deep brain stimulation. Before her career as a science writer, she earned a Ph.D. in neurobiology and worked in the U.S. biotech industry.

Rohan Jain