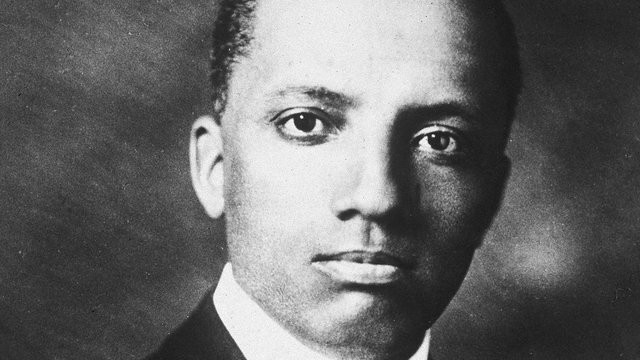

In 1933 Dr. Carter G. Woodson published The Mis-Education of the Negro, an examination of the racist educational system and the lasting detrimental effects of this system upon the minds of young African Americans. Woodson, a revered and pioneering scholar of Black History, argues that the African American youth are indoctrinated to believe that they are inferior, subservient, and dependent upon the upper class. Woodson laments the fact that African History is largely excluded from class textbooks, even in all-black schools. Jane Martin, in the introduction to her book Cultural Miseducation, notes a critical insight from Plato’s Republic: Society, “if left to its own devices, is apt to transmit cultural liabilities to the next generation instead of cultural wealth” (Martin 1).

Whether or not society being “left to its own devices” is to blame, black mis-education is an issue that is still very much relevant today, an era in which cursory lectures on slavery and “triangular trade” are practically the only perspective on African History provided. Woodson suggests that this tendency in our society to teach a white, European version of history “stimulates the oppressor with the thought that he is everything and has accomplished everything worthwhile,” and “crushes at the same time the spark of genius in the Negro by making him feel that his race does not amount to much and never will measure up to the standards of other peoples” (Woodson 5). In other words, our educational system does not have to explicitly tell blacks that they are inferior in order to indoctrinate them with this warped perception. By presenting a European conception of history, our system suggests by implication that whites are both the standard of normalcy and the great achievers of history. Meanwhile, our popular culture crafts an ideal that is utterly unattainable for non-white Americans, and hardly attainable for most whites, but is supposedly within reach for everyone. Whether it comes from school, television, radio, or just about anywhere in between, all of us are mis-educated to believe that we are inadequate. The famous philosopher and psychiatrist Carl Rogers proposed that all humans hold in their mind an “ideal self” and a perceived “real self.” The further the disparity between the two, according to Rogers, the more likely an individual is to suffer from depression, addiction, and a slew of anxiety and behavioral disorders. In varying degrees, a modern American education universally promotes this estrangement of the ideal and real. All of us devalue ourselves with respect to celebrities, who generally possess some talent or physical trait that we associate with popularity and success. However, this “mis-education” is inflicted most heavily upon people of with dark skin. Whiteness is treated as a cultural norm, an aesthetic ideal, which renders all dark-skinned people monstrous with respect to this warped perception of normalcy.

The circumstances are worrisome for all of America’s youth. We are all made to feel inadequate by unattainable standards of beauty and self-identity, but the dangers are considerably greater for non-white Americans. Woodson tells us that “While being a good American,” a black student must also “above all things be a ‘good Negro’; and to perform this definite function he must learn to stay in a ‘Negro's place’” (Woodson 7). Every race has its stereotypes, which span a range of positive and negative attributes. However, whites are usually treated as the norm against which the other stereotypes are compared. In contemporary American literature, for example, fictional characters are rarely introduced specifically as “white”; we take this description for granted. But black, Hispanic, Asian, or Arab characters are almost always noted as such, because they differ from the norm.

In their book Race and Cyberspace, Kolko, Nakamura, and Rodman argue that visual culture depicts race in a manner comparable to binary code. Rather than provide a nuanced, comprehensive portrait, visual media in the modern age treats the subject of race like “one of those binary switches: either it’s completely ‘off’ or it’s completely ‘on’” (Kolko 1). Race is either ignored entirely or made the center of sweeping, controversial debates. When race is present in the conversation, human beings are categorized as easily as 1’s and 0’s, without regard to the subtleties of identity.

The popular, animated television-series Family Guy projects white normalcy coupled with a binary vision of race. All of the characters are cleanly divided into their races with no room for ambiguity. All of the white people are the same shade of beige. All of the black people are the same shade of brown. Et cetera. This portrayal of uniform racial groups reinforces a racist perception of the world. It also promotes white normalcy because the majority of the characters are white, and the only non-white characters are afforded virtually no identity outside of their racial stereotypes. Peter Griffin, his family, and the other white citizens of Quahog are all, for the most part, original characters, whose lines and endeavors are only marginally determined by racial stereotypes. On the other hand, the only recurring hispanic character is a nagging and incomprehensible maid, the only recurring asian character is an equally vacuous and stereotypical news reporter, and neither character is ever afforded any back-story or agency in the plot. If asians are brought in otherwise, they are inevitably depicted in some cliched and offensive scenario. For example, an asian woman driving without turn signals while narrating her actions in broken english. Black characters, though more prevalent, are unanimously portrayed with the same flatness of character. Peter’s black friend Cleveland, who appears in almost every episode— and even got his own show, The Cleveland Show— becomes an endless fountain of racist humor, as does any character that isn’t the same uniform beige.

Family Guy frequently attempts to combat racism “ironically,” but in many cases these gags would be better off unattempted. Excessively racist jokes are often made specifically because they are so racist and unethical. Black people that can’t swim, Asian people that can’t drive, Jewish people that fawn over pennies— we are meant to laugh at the absurdity of these racial stereotypes, but Family Guy never offers any alternative to these stereotypes. No character, except a white one, is allowed to create any identity that is not shackled to race. Even Cleveland and his family in The Cleveland Show are depicted in decidedly racist terms, which is unsurprising when the show is simply a “black” version of Family Guy. One of Cleveland’s children is a not-so-subtle rip-off of Huey and Riley Freeman from The Boondocks, a fact that is humorously admitted by Cleveland in more than one episode. However, unlike the heroes of The Boondocks, who crusade for civil rights and social justice, Cleveland’s children are two-dimensional caricatures of black culture, with virtually no insight into anything.

Perhaps this is why all three of Seth McFarlane’s popular animated series— Family Guy, The Cleveland Show, and American Dad— each made Complex Magazine’s list of the “50 Most Racist TV Shows.” Whatever Seth MacFarlane’s intentions, and they may very well be good intentions, his shows implicitly and explicitly promote a vision of white normalcy, which is especially concerning given Family Guy’s immense popularity and primetime slot on Fox. Sadly, the notion of a “Negro’s place” as invoked by Carter G. Woodson, is still glaringly apparent in many areas of our culture. It is a notion that has grown so large we can hardly determine its shape.

Take the newer show Black-ish, for example. The premise of this family-oriented sitcom, starring Anthony Anderson and Lawrence Fishbourne, is that Anderson’s family is friendly, affluent, moderately wealthy, and black. But, by virtue of their affluence, intelligence, friendliness and financial success, they are no longer really black. They are black-ish. The show, I presume, does not actually endorse the idea that unintelligence, violence, or poverty are essential aspects of black culture, but the title and the premise make this implication utterly unavoidable.

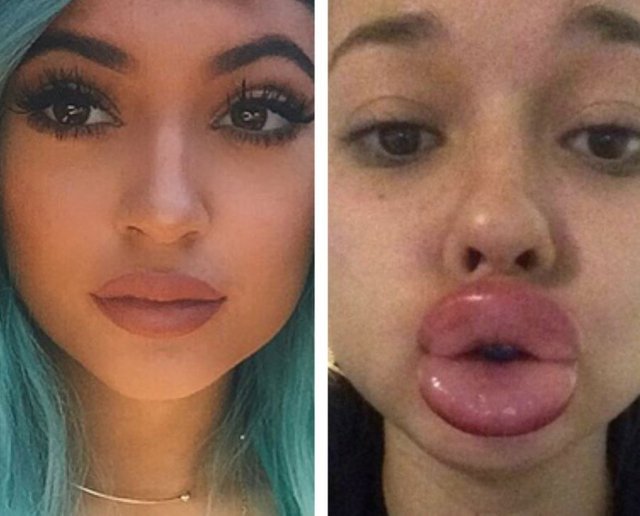

The message presented by media, whether it be a sitcom, the news, or popular music, has a huge effect on self-perception. Teenage girls see how popular Kim Kardashian’s sister Kylie Jenner is, and they all want to quite literally be her. Consequently, the hashtag “#kyliejennerchallenge” was at one time trending on twitter, as thousands of young girls attempted to make their lips look as big and “attractive” as Jenner’s (Moyer). Unfortunately, the technique for lip-plumping requires a shot-glass and air pressure, resulting only in bruising and humiliation. It should be noted that in order for something to become a bonafide “trend” on twitter, thousands and thousands of people need to participate. It is a frightening statistic: teenaged American twitter users are more likely to use shot glasses to look like a Kardashian than they are to pursue social change.

Twitter provides a good barometer for racial philosophy in America. Another trend that has emerged in the past few years, far more disturbing than the Jenner lips controversy, is the ongoing “dark skin vs light skin” debate, in which teenagers of African descent judge themselves and their peers based on stereotypes of white normalcy and black imperfection. In this twisted genre of “humor,” black high school students refer to their own “dark skin” classmates as dumb, ugly, ignorant, violent and unemotional, while referring to “light-skins” as smart, sexy, learned, amiable, and sensitive. The trend was reignited in earnest in 2014, when a black singer named Tank made a post which read: “What do dark skinned women have against light skinned women? Aren't we all black at the end of the day??” One could talk for days about the implications of this statement, but suffice to say Tank undermines his own rhetorical question “aren’t we all black??” by segregating black women into the sub-races “light-skins” and “dark-skins,” the latter of which he generalizes as spiteful. The “dark skin vs light skin” debate is particularly saddening, as it demonstrates the powerful influence of our mis-education. Even amongst the black community at large, blackness is invariably treated as a flaw and whiteness as a virtue.

The only way for us to achieve a truly “post-racial” society is for us to gradually expel race from the conversation entirely. As long as people are categorized by arbitrarily defined “races,” we will persist in lumping people into these groups and ignoring their individual identities. We are all human, and we should recognize by now that skin-tone should not imply a single thing about a person’s character. In the current paradigm, white people are the only ones afforded the dignity of crafting their own identities, but even still— the culture at large reminds us that celebrities are the pictures of success, while the rest of us are pictures of the opposite. We live in a culture that normalizes whiteness, degrades blackness, and creates an ideal that nobody can ever hope to fulfill. The effect of this mis-education is to make blacks, and all Americans, blame themselves for their abandonment and economic woes, instead of blaming the economic system which has actively oppressed them, disenfranchised them, and belittled them. Linguist and political scientist Noam Chomsky in his collection of interviews On Democracy and Education, tells us that “to protect the opulent minority against the majority,” citizens must be “controlled at the workplace” and “kept out of the political arena” (Chomsky 238). What better way to instill political apathy, than to convince Americans that the only flaws lie within them?

Cover Photo: Image Source

Excellent post. I totally with you on that. I am actually working on a similar post that has to do with stereotypes and what some people may call reverse racism.

Most people don't see the pervasive effects of the media on racial and political issues. it normalizes abnormality and discrimination.

Awareness needs to be raised even today, after so much has happened and been done.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

@youdontsay esperemos que esas diferencias raciales en nuestros paises dentro de poco ya no existan y seamos una sola comunidad. Saludos y buena publicación

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Family guy is terrible, luckily schools have changed a lot since 1933.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Great input and insight in this post.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit