I took advantage of being at the seaside to lay in a store of sucking-stones. They were pebbles but I call them stones. Yes, on this occasion I laid in a considerable store. I distributed them equally between my four pockets, and sucked them turn and turn about. This raised a problem which I first solved in the following way...

Come on, we've all done it... These are the opening lines of the ‘Sucking Stones’ monologue, spoken by the protagonist Molloy, in Samuel Beckett’s novel of the same name. After Waiting For Godot it is perhaps his most celebrated work, and the monologue itself has been as endlessly performed and interpreted in the decades since it first saw publication. It’s immediate appeal is not difficult to see.

Compared to the rest of the book, it marks an uncharacteristically lucid moment for Molloy. A character who - we can never be sure - is either one or two people, and prone to extended periods of inner reflection. On the face of it, this simple passage detailing his efforts to suck sixteen stones equally, “turn and turn about”, could be written off as an odd quirk of his personality, a comedic interlude without any lasting significance.

However, Beckett isn’t one to go for throwaway gags. Simplicity so often belies complexity, and in this case it is complexity itself which is in question. At the heart of this monologue is an interrogation of the complexity which we design around our lives, belying the simplicity which guides them.

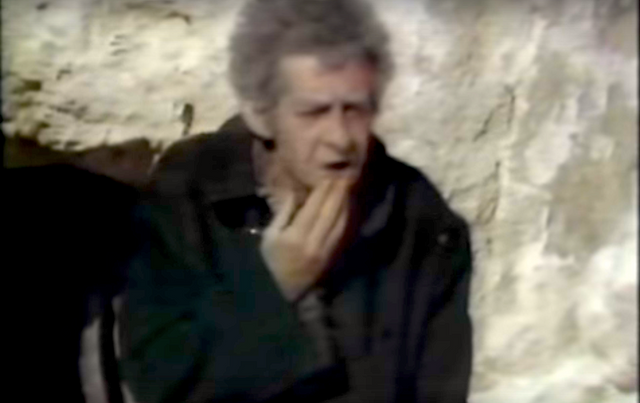

Before we go any further, I welcome you to read the monologue for yourself, or watch this excellent performance from Jack MacGowran if you’d prefer. If not, I’ll now paraphrase it here, although as I’m no Beckett it is doubtful I will achieve the same hypnotic, fantastical effect...

Having acquired his store of sixteen stones and distributed them equally in his four pockets - which is to say, four stones in each - Molloy devises a system by which to suck them all in turn.

Taking a stone from the right pocket of my greatcoat, and putting it in my mouth, I replaced it in the right pocket of my greatcoat by a stone from the right pocket of my trousers, which I replaced by a stone from the left pocket of my trousers, which I replaced by a stone from the left pocket of my greatcoat, which I replaced by the stone which was in my mouth, as soon as I had finished sucking it. Thus there were still four stones in each of my four pockets, but not quite the same stones.

He soon realises, however, that his methodology is flawed. It does not escape him that by some “extraordinary hazard”, he might only be sucking the same four stones instead of the full sixteen. Not willing to accept this potential tragedy, he devises a new system, moving the stones between his pockets all four at a time. Again, he realises, the potential remains the same.

Now the task seems impossible. “The truth is I should have needed sixteen pockets in order to be quite easy in my mind,” he laments, resigned to the idea he will never be able to enjoy his stones as intended. He could partition his pockets with safety pins to create sixteen spaces in effect, however, “I did not feel inclined to take all that trouble for a half-measure.”

And if I was tempted for an instant to establish a more equitable proportion between my stones and my pockets, by reducing the former to the number of the latter, it was only for an instant. For it would have been an admission of defeat.

Then one day, he has an epiphany. If he is willing to sacrifice the principle of equal distribution - with four stones in each pocket - a solution is at last attainable. Placing six stones into the top-right pocket, five into the bottom-right, and five into the bottom-left, he leaves the top-left empty. He is then free to suck the first six stones one by one, afterwards depositing them into the empty pocket. Once this is done, each pocket of stones can be rotated to the next, until the top-left is empty again. Repeat ad infinitum.

There was something more than a principle I abandoned, when I abandoned the equal distribution, it was a bodily need. But to suck the stones in the way I have described, not haphazard, but with method, was also I think a bodily need. Here then were two incompatible bodily needs, at loggerheads. Such things happen.

What drew me to this monologue when I first read it is how eerily familiar it all feels. Not the specifics of the stones, the equal distribution, or the sucking thereafter, but more so the general sense of compulsion which it entails. Molloy presents it as given that he should be so consumed by sucking stones, that it is a “bodily need” as much as any other, and so the question of ‘why’ becomes irrelevant. Like breathing, the simple act of sucking stones is a self-evident necessity. It’s not even clear that he takes any real joy from it.

What matters is the procedure. If the stones must be sucked (and, as far as Molloy is concerned, they must) then all that remains to decide is in what way, to achieve the greatest satisfaction or efficiency. Which for Molloy are more or less the same thing. It is here that his sense of compulsion becomes universal, reflecting at its core the manner in which we implement other, less alien human drives.

The drive to be understood? We create art, write books, give monologues. The drive to be loved and to belong? We seek out relationships, strike conversations, adapt to others’ expectations. The drive for safety, for physical wellbeing? We take on jobs, strive to better our position, try to live healthier lives.

Perhaps these seem a far cry from sucking stones on a beach, and it’s true that they at least bring about a more tangible pleasure. Molloy is not a well balanced individual, however. His bodily needs here are trivial by comparison, yet it is for that reason that need itself can become the primary focus of the monologue. By stripping away the emotivity which we invest in our real life needs and desires, making Molloy on the surface utterly unrelatable, Beckett shines a spotlight on the underlying drive itself. That we may find need-fulfilment pleasurable is besides the point. It is essential.

Or, at least - and this is where things start to get confusing - Beckett lets us think he thinks that. There has been much debate as to whether his work reflects Existentialist or Absurdist philosophy, or none at all. This seems natural, considering he wrote about similar themes to such associated thinkers as Camus, and Sartre, and indeed was their contemporary. In light of this, and acknowledging the general Existentialist position of ‘confusion and dread in the face of a meaningless, inconsistent world’, the conclusion to the monologue seems to undo much of what it has so far accomplished. In keeping with the spirit of it, I have saved these lines until the very end.

Is the fulfilment of instinctive drives really an essential source of meaning in our lives? Does the way we go about it have any significance in the scheme of things? Are sixteen stones in fact any better than one? These questions I leave up to you.

Deep down it was all the same to me whether I sucked a different stone each time or always the same stone, until the end of time. For they all tasted exactly the same. And if I had collected sixteen, it was not in order to ballast myself in such and such a way, or to suck them turn about, but simply to have a little store, so as never to be without. But deep down I didn't give a fiddler's curse about being without, when they were all gone they would be all gone, I wouldn't be any the worse off, or hardly any. And the solution to which I rallied in the end was to throw away all the stones but one, which I kept now in one pocket, now in another, and which of course I soon lost, or threw away, or gave away, or swallowed...

I think the recognition and respect of basic drives is absolutely essential for mental/emotional health, but the fulfillment is less so if it does not directly preserve life. I wrote a story about this concerning repression. If you are interested here is a link. https://busy.org/@giddyupngo/short-story-13-horses-part-1

The 2nd part is here.https://busy.org/@giddyupngo/short-story-13-horses-explanation-part-2

I have never read any of Beckett, though I have heard of him. Thanks for expanding my horizons. :-)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Your story makes an interesting point - it's certainly true that focussing on one drive in particular, or just allowing it to 'take the reins' as it were, is a recipe for disaster! I think, in a way, the madness of Molloy in the extract above shows what can happen in such circumstances.

Then again, viewed side by side, I think these two stories actually show two sides of that age old philosophical debate; is passion or reason, ultimately, in charge? In yours, reason is the young boy holding the reigns, whereas in Molloy's case, these 'reigns' are absent or at best an illusion. Passion, in yours, is secondary to the will to control it, whereas for Molloy it constitutes his will entirely.

Interesting to think about at any rate, although I doubt we'll get to the bottom of it here, haha. Thank you for sharing such an illuminating write with me :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks for reading it, and you read me correctly, reason should have the reigns in my opinion. Take care.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

My friend, a mathematition, enjoys all the elements of combinatorics in Beckett's works (Molloy is not the only work, where such mindblowing scenes can be found)... Another friend of mine, who is into arthouse cinema, also finds a lot of enjoyment reading Beckett, he is always in search of something new: new impressions, new concepts...

I see it absolutely differently.

When I started to read the first part of Molloy, I saw one's stream of consciousness, and if you follow it along, you learn a lot about this man. Speaking unclear, he's trying to tell us about himself, but his conscious mind leads him far far away from what was intended to be said. And at some point I realize that I'm getting a chance to see someone from the inside, wander in his subconscious, who crossed a certain line when he maybe doesn't need anyone anymore, consumed with himself, losing simplicity, is he even interested in other people's feelings?.. Frightening.

Your post reminded me of the existence of the line, Lazarus )

Haha, I surely moved away from the "stone" topic you raised)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Not to worry about going off topic, these tangents are often much more interesting!

Molloy's depth and transience as a character is profound indeed, and that fine 'line' as you put it between personalities and people quite troubling. I find him a lot more readable than Joyce's stream of consciousness in 'Portrait of an Artist', mostly for the insights on consciousness which he brings to bear. Beckett's work generally is pretty mysterious - there's few others like him.

Appreciate your perspective on this :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I think the recognition and respect of basic human drives is absolutely essential for mental/emotional health, but the fulfillment is not essential if it does not directly preserve life. I wrote a story about this concerning repression. If you are interested here is a link. https://busy.org/@giddyupngo/short-story-13-horses-part-1

The 2nd part is here.https://busy.org/@giddyupngo/short-story-13-horses-explanation-part-2

I have never read any of Beckett, though I have heard of him. Thanks for expanding my literary horizons. :-)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi lazarus-wist,

LEARN MORE: Join Curie on Discord chat and check the pinned notes (pushpin icon, upper right) for Curie Whitepaper, FAQ and most recent guidelines.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit