Introduction

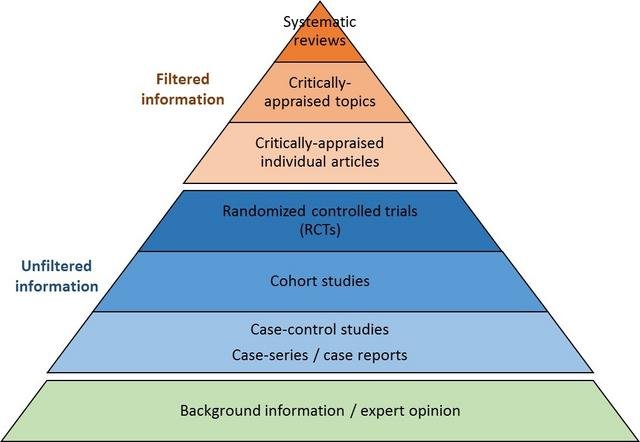

Whether you are writing a dissertation / thesis or simply want to understand more about a specific topic, it may be required or important for you to do a literature review (LR) on that topic. Knowing the basics of writing this type of document is necessary, especially if you have to do it in an academic context. What exactly is a LR? It can be defined as the summary of all research findings of a particular field or topic. Basically, the classic LR resumes what has been written so far on a given topic: its state-of-the-art. Although providing the big picture of a topic can be an end in itself, it can also be employed as a means to produce different outcomes. This is because most LR are generally written to serve specific purposes such as refuting or supporting an argument / hypothesis / assumption, justifying the integration of a new research framework / the need for a development of new theories / concepts… etc. Since it exists many forms of LR, you need to clearly define your research objective(s) beforehand in order to adopt the appropriate review methodology. In this article, the focus is on the systematic literature review (SLR). It is a form of review that follows a strict protocol and obeys to the four principles of specificity, objectivity, transparency and replicability. As a young researcher, I feel that it is vital to underline this topic so I will try to cover the key points that need to be checked before starting a SLR. As its name indicates, a SLR must be done by pursuing a precise methodology to ensure the negation of bias, the conformity to the four principles and most importantly, the high quality and reliability of the review. First and foremost, it cannot cover a whole part of a science or a topic that is too broad or vague. For example: a SLR of microeconomics would be irrelevant because the domain is too vast and too many subdomains exist. That is why we need to be more specific. A SLR seeks to answer a research question, preferably on a narrow topic. For instance: does responsible investment have a positive impact on the transition to the low-carbon economy? may be easier to answer than: what contributes positively to the transition to a low-carbon economy? Objectivity is crucial in a SLR: judgements must be made in a neutral and scientific-based manner. That means you may identify contradictions and discrepancies in findings, inconsistencies in research evidence, describe new research directions or analyse of researchers’ flaws without having to weight in your personal opinion, feelings and preferences about a particular idea, author or institution. This is no easy task but a SLR is prone to bias if it is written in a subjective way. A great SLR can be replicable by other reviewers if the same methodology is applied. This principle is directly linked with the transparency of the whole process. One must be able to answer questions like: Why such articles are excluded? Why the ones in the review are included? Why this author does not appear in the review? Why only clinical trials from 2000 to 2005 are considered? … etc. Thus, the inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as other important selection methods must be clearly explained and present in the beginning of the SLR. All of the aforementioned characteristics make a SLR unique and on top of the hierarchy of scientific evidence (general guideline). This approach is widely used in medicine because of its usefulness in terms of important practical implications but we can of course employ it in every domain.

Hierarchy of evidence. Source: La Trobe University.

The three parts that structure this article reflect the chronological steps to be taken in order to write a proper SLR: I. Research question and data compilation II. Inclusion / exclusion criteria determination III. Articles selection

I. Research question and data compilation

As mentioned in the introduction, you cannot begin your search if you do not even know what you want to answer. It should not take you a lot of time to define your research question(s) but it definitely is an essential step for the process. Keep in mind that the narrower and more precise the focus, the easier and the more reliable your SLR will be. Once you have your question(s) ready and before you even go searching blindly for articles on Google by typing the whole research question(s), think of the following points:

- Database: Which sources contain more articles relating to your topic? Are they reliable? Do not ignore unpublished articles, search in all relevant databases. Just because a research finding is not published does not necessarily mean it is of low quality. Sometimes, negative results or authors’ lack of interest in public disclosure can also lead to non-publication of articles. Rely on more than one source to vary your data. Examples of database and search engines: Google Scholar, MedLine, Cochrane, CNRS, INSEE, JStor, Elsevier, Research Gate… etc. It is surely easy to search on an electronic database but consider also searching in libraries.

- Terms used for searching: Again, use specific words or phrases and also search using synonyms / similar terms. Pay attention to the language vocabulary when searching for articles in different countries (e.g. some words that differ in UK English and American English).

- Refined search: Typing the whole question (plus the interrogation mark) into the search bar is not the most effective way to obtain the data that we want. Instead, put only keywords and omit articles like a, the, in, to… etc. For example: write “euthanasia Europe legality” instead of “what is the legality status of euthanasia in Europe?”. If you search engine or database permits, use conditional or logical search criteria to narrow your search (e.g. Boolean operators “and/or” and truncation symbols).

It is recommended to keep a record of your searches in a table as detailed as possible. This allows you to track your progress and help you know when, what and how you searched to avoid wasting time. The goal at this point to gather the most data on your question or topic. The screening comes in the next step but do not forget, you will need to justify every decision you make including this very first step of data collection.

II. Inclusion / exclusion criteria determination

The most important part of the SLR process is the determination of inclusion and exclusion criteria. After obtaining a pile of data from your preliminary search, it is now time to screen out data that is irrelevant for your study. Even though all articles’ titles or subtitles seemed related to your topic or question in the first place, you will have to apply additional filters to take out only the most relevant articles. The criteria commonly used are for example:

- Year of publication: Does an article from twenty years ago still interest you? If you want to examine only the most recent articles, what is the threshold? Five years maximum?

- Research techniques: Do only results from a quantitative or qualitative analysis interest you? Only samples from randomisation process?

- Socio-demographic and geographic characteristics: Only results from women aged 40 to 60? Only people who work in the mining industry? Only male adults from Southern Africa?

Of course, you can create more filter that adapts to your topic or interest. But the more criteria you define, the less data you might end up with, so consider this point carefully when you design your research question and scope your topic unless you want to prove the lack of research efforts on a particularly important topic (e.g. public health). Normally, the screening process can be done through the abstracts of articles.

III. Articles selection

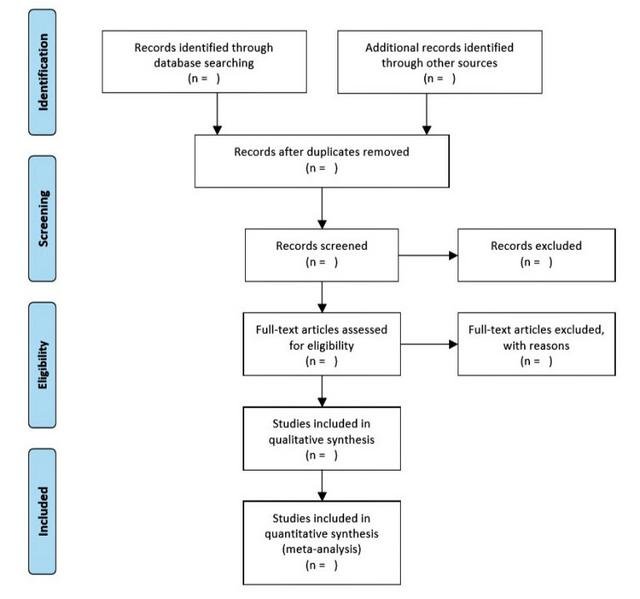

The PRISMA flow diagram is a great tool for tracking information during the different phases of the SLR.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram. Image source here.

Now that the screening is done, you simply have to read the full-texts and if necessary, exclude for the last time articles that are ineligible. Beyond this point, your analytical skills will take the relay. Remember that there is no best way or a unique right method to write a SLR. Stay as unbiased as possible and always avoid unnecessary judgements. Another form of review is the meta-analysis which can be defined as the analysis of analyses, mainly for quantitative results. Due to its technical complexity, I will not cover it here.

Keywords

- Methodology

- Protocol

- Standardisation

- Research question

- Rigour

- Transparency

- Replication

- Objectivity

- State of the art

- Inclusion / exclusion criteria

- Record keeping

References

Siddaway, A. (n.d.). What is a systematic literature review and how do I do one? https://www.stir.ac.uk/media/schools/management/documents/centregradresearch/How%20to%20do%20a%20systematic%20literature%20review%20and%20meta-analysis.pdf

A guide for writing scholarly articles or reviews for the Educational Research Review https://www.elsevier.com/__data/promis_misc/edurevReviewPaperWriting.pdf

University of Southern California. (2017). How to conduct a literature review: types of literature reviews. http://guides.lib.ua.edu/c.php?g=39963&p=253698

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://sothearathseang.wordpress.com/2017/11/20/the-systematic-literature-review/

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Yes it is the same article from my blog :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit