The mediating role of sleep in the fish consumption – cognitive functioning relationship: a cohort study

Greater fish consumption is associated with improved cognition among children, but the mediating pathways have not been well delineated. Improved sleep could be a candidate mediator of the fish-cognition relationship. This study assesses whether

- more frequent fish consumption is associated with less sleep disturbances and higher IQ scores in schoolchildren,

- such relationships are not accounted for by social and economic confounds, and 3) sleep quality mediates the fish-IQ relationship.

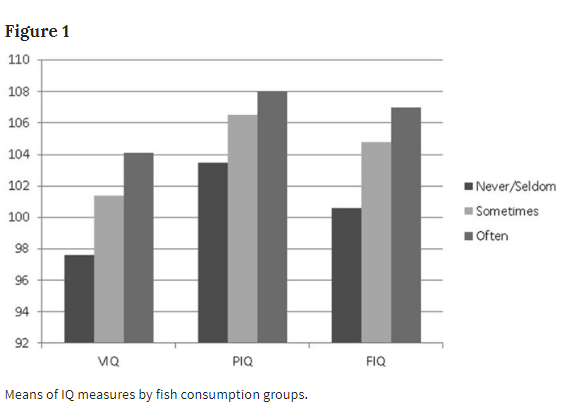

In this cohort study of 541 Chinese schoolchildren, fish consumption and sleep quality were assessed at age 9–11 years, while IQ was assessed at age 12. Frequent fish consumption was related to both fewer sleep problems and higher IQ scores. A dose-response relationship indicated higher IQ scores in children who always (4.80 points) or sometimes (3.31 points) consumed fish, compared to those who rarely ate fish (all p < 0.05). Sleep quality partially mediated the relationship between fish consumption and verbal, but not performance, IQ. Findings were robust after controlling for multiple sociodemographic covariates. To our knowledge, this is the first study to indicate that frequent fish consumption may help reduce sleep problems (better sleep quality), which may in turn benefit long-term cognitive functioning in children.

The long-chain omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are essential nutrients primarily found in fish1 and have gained increasing attention for potential health benefits ranging from cardiovascular to mental health2,3. As omega-3 fatty acids are known to play critical roles in the growth and functioning of neural tissue1, their effects on cognitive outcomes are of particular interest. Maternal fish intake or fish oil supplementation during pregnancy, for instance, is associated with improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants and young children, including language and visual motor skills at 6 and 18 months4, eye and hand coordination at age 2.5 years5, and IQ at age 4 years6. Dietary fish and omega-3 fatty acid intake is also associated with improved cognitive and academic performance in adolescents7,8,9 and reduced cognitive decline and dementia in older age10,11,12.

While animal models have demonstrated the role of omega-3 fatty acids on cognitive processes on a more molecular level13,14, our knowledge regarding how they improve observed cognitive performance remains limited. One pathway that has yet to be explored is sleep. Sleep is well studied in its association with cognitive function in both children15,16,17 and adults18,19, with insufficient or poor quality sleep being associated with poor school performance and objective measures of learning and memory15,20. Sleep itself is also affected by omega-3 fatty acids via several mechanisms. Animal studies have suggested the potential role of DHA in regulating endogenous melatonin production21,22,23 which has been shown to regulate circadian rhythm and improve sleep organization24 as well as CNS maturity in infants25,26. Additionally, essential fatty acids have been involved with the production of prostaglandins. Prostaglandins are believed to be the most potent endogenous sleep-promotion substance and are well known to mediate sleep/wake regulation27 and responses of synaptic circuitry to sleep deprivation28. Epidemiological studies have also demonstrated significant associations between increased fish intake and improved sleep measures in adults29,30 as well as infants25,26 and children31.

In light of the relationship between sleep and cognition, as well as the growing recognition that omega-3 fatty acids may lead to both improved sleep quality and cognitive outcomes, the possibility that sleep acts as a potential mediator between fish intake and improved cognition warrants further exploration and consideration. However, to our knowledge, no study has simultaneously examined how dietary fish and omega-3 fatty acid intake affects sleep and cognition. Furthermore, studies of dietary omega-3 fatty acid consumption in school-aged children examining cognition4,7,8,9 and sleep31 have primarily been limited to Western countries, with the latter relationship only reported by one study to date in healthy school-aged children31.

The present study aims to address these gaps and add to the current literature by examining dietary fish intake, sleep quality, and cognitive outcomes in a large sample of healthy, Chinese schoolchildren. The purpose of this study is thus to examine the following hypotheses: 1) frequent fish intake is linked to better sleep and long-term cognitive outcomes; 2) such relationships are robust to sociodemographic covariates; and 3) sleep mediates the fish intake and long-term cognitive outcome relationship

Study population

This longitudinal study consisted of a sample of 541 Chinese school children (54% boys and 46% girls) aged 12 years from the second wave of the China Jintan Cohort Study, an ongoing prospective longitudinal study. Details on sampling at baseline and research procedures have been published elsewhere32,33. Of 1009 children who were followed up in the second wave (2011–2013), 541 participants who completed a self-reported food frequency questionnaire, IQ measurement, and sleep quality evaluation were included in the present study. With the exception of father’s education and home location, there were no significant differences in social demographic features between children with and without complete data. Written informed consent was obtained from parents, and approval from Institutional Review Boards was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania and the ethical committee for research at Jintan Hospital in China. All research was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measures

Fish consumption at age 9–11

A self-administrated food frequency questionnaire was used to collect information on diverse food intake, including fish consumption, when children were enrolled in 4th, 5th, and 6th grades. Fish intake frequency was measured by asking children the following question: “How often do you consume fish in a typical month? 1 = never, 2 = seldom (less than 2 times per month), 3 = sometimes (2–3 times per months), 4 = often (at least once per week)”. After preliminary analysis, categories 1 and 2 were combined due to very few “never” responses. Therefore, our analysis is based on three levels of fish consumption: “often”, “sometimes”, and “never or seldom”.

Sleep quality at age 9–11

Sleep quality was measured by the total sleep disturbance score, derived from parents’ report of sleep patterns in the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ). The CSHQ consists of 33 sleep-disturbance items, which are conceptually grouped into 8 subscales: bedtime resistance, sleep-onset delay, sleep duration, sleep anxiety, night waking, parasomnias, sleep-disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness. Parents were asked to rate each item on a 3-point scale: “usually” if the sleep pattern occurred five to seven times/week; “sometimes” two to four times/week; and “rarely” zero to one time/week in a typical week during the past month. A total sleep disturbance score was calculated as the sum of all eight subscale scores, with higher values indicating more sleep disturbance and poor sleep quality34. The Chinese version of the CSHQ has displayed satisfactory psychometric properties in the assessment of sleep problems in Chinese children35 and has been widely used36,37,38.

Cognition (IQ) at age 12

IQ assessments were performed using the Chinese version of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised (WISC-R). The WISC-R consists of six verbal subtests (Information, Comprehension, Arithmetic, Vocabulary, Similarities and Digit Span) that are summed to form Verbal IQ, and six non-verbal subtests (Picture Arrangement, Picture Completion, Object Assembly, Block Design, Coding and Mazes), that are summed to form Performance IQ. The Verbal and Performance IQs are combined to produce a Full-Scale IQ score. The Chinese version of WISC-R has long been standardized and shown to be reliable among Chinese children39. In the present study, all IQ tests were administered by two intensively-trained researchers to minimize possible investigator bias. Details of IQ test procedures have been reported elsewhere40,41.

Covariates

Sociodemographic and other relevant information collected at baseline was used as covariates in the current study; they include gender, parental education, parental occupation, parental marriage status, maternal age at childbirth, feeding type during infancy (breastfed or bottle-fed), breastfeeding duration, home location (city, town, or countryside), and siblings (yes/no). Parental education was categorized into three groups: less than high school, high school, and college or higher. Parental occupation was collapsed into unemployment, working class, and professional class. In addition, since our previous research has shown breakfast intake as an important protective predictor for cognitive function, breakfast consumption was included in the analysis as a controlled confounder.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of child participants and their families were summarized using descriptive statistics (mean/standard deviation, median/interquartile range, and frequencies/percentages, as appropriate). Comparisons across fish consumption groups were accomplished using chi-square statistics or Fishers Exact tests and one-way ANOVA models or nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis models for categorical and continuous measures, respectively. Bivariate associations of IQ measures and total sleep disturbance scores with various baseline covariates were evaluated using general linear modeling (GLM). Robust variance estimation was used in all GLM analyses to account for possible correlations within geographic region (preschools and primary schools). GLM analyses were also applied to assess the associations of IQ measures with fish consumption frequency and total sleep disturbance score. Multivariable GLM analysis adjusted for possible confounders such as gender, father’s education, mother’s education, siblings, home location, and breakfast consumption habits. Finally, a 4-step mediation analysis was conducted to evaluate if total sleep disturbance mediates the association between fish consumption habit and IQ measures42. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.243; two-sided p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Basic characteristics of study population

Of 541 schoolchildren aged 12 years, 137 (25.3%) reported consuming fish often (at least once per week), 315 (58.2%) reported eating fish sometimes (2-3 times per months), and 89 (16.5%) never or seldom ate fish (less than 2 times per month). With the exception of home location (p = 0.038), there were no significant differences in baseline socio-demographic characteristics by fish consumption (Table 1). IQ measures and the total sleep disturbance score demonstrated a significant association with fish consumption: as compared to children who never or seldom ate fish, those having more frequent fish intake had higher verbal, performance, and full scale IQ scores, as well as a lower total sleep disturbance score (all p < 0.05). Distributions of average IQ scores by fish consumption groups are displayed in Fig. 1.

Simple bivariate associations between total sleep disturbance and the three IQ scores with demographic and relevant covariates are summarized in Table 2. While gender, parental education and occupation, and home location were consistently associated with the three IQ measures, only the number of siblings and breakfast consumption habits were significantly associated with verbal and full scale IQ. Moreover, the total sleep disturbance score was found to be significantly associated with parental education and occupation, maternal age at childbirth, home location, and number of siblings.

It is a detailed study about nature, how it functions

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit