You can train your brain to think better. One of the best ways to do this is to expand the set of mental models you use to think. Let me explain what I mean by sharing a story about a world-class thinker.

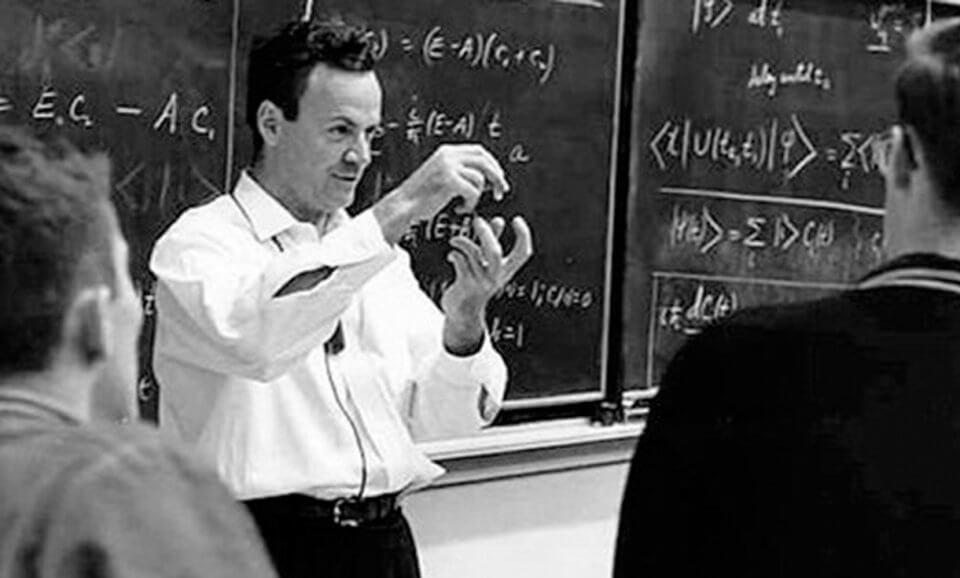

I first discovered what a mental model was and how useful the right one could be while I was reading a story about Richard Feynman, the famous physicist. Feynman received his undergraduate degree from MIT and his Ph.D. from Princeton. During that time, he developed a reputation for waltzing into the math department and solving problems that the brilliant Ph.D. students couldn’t solve.

When people asked how he did it, Feynman claimed that his secret weapon was not his intelligence, but rather a strategy he learned in high school. According to Feynman, his high school physics teacher asked him to stay after class one day and gave him a challenge.

“Feynman,” the teacher said, “you talk too much and you make too much noise. I know why. You’re bored. So I’m going to give you a book. You go up there in the back, in the corner, and study this book, and when you know everything that’s in this book, you can talk again.”

So each day, Feynman would hide in the back of the classroom and study the book—Advanced Calculus by Woods—while the rest of the class continued with their regular lessons. And it was while studying this old calculus textbook that Feynman began to develop his own set of mental models.

“That book showed how to differentiate parameters under the integral sign,” Feynman wrote. “It turns out that’s not taught very much in the universities; they don’t emphasize it. But I caught on how to use that method, and I used that one damn tool again and again. So because I was self-taught using that book, I had peculiar methods of doing integrals.”

“The result was, when the guys at MIT or Princeton had trouble doing a certain integral, it was because they couldn’t do it with the standard methods they had learned in school. If it was a contour integration, they would have found it; if it was a simple series expansion, they would have found it. Then I come along and try differentiating under the integral sign, and often it worked. So I got a great reputation for doing integrals, only because my box of tools was different from everybody else’s, and they had tried all their tools on it before giving the problem to me.”

Every Ph.D. student at Princeton and MIT is brilliant. What separated Feynman from his peers wasn't necessarily raw intelligence. It was the way he saw the problem. He had a broader set of mental models.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://jamesclear.com/feynman-mental-models

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit