This is not a political article. The merits of a nation state opening its borders to migrants and to what degree and whether this has a positive or negative affect on a macro-economy or on the lives of a nation’s home-born locals is not a topic this post is concerned with. Instead, this is an examination into why the average voluntary immigrant is more financially successful than the average native citizen of their host nation and by extension what we perhaps can learn about our lives and how we conduct them, and how immigrants conduct theirs, to give us the knowledge we need to see greater financial success for ourselves and our children.

The fact that the average voluntary immigrant will make more money in their lifetime than the average native born citizen may be a surprise to you. The research however attests to this; most voluntary immigrant groups are increasingly better educated[i], have higher savings rates[ii], and earn more[iii] than their native counterparts. They are therefore less reliant on their state pensions for retirement, are more entrepreneurial[iv] and also more likely to become millionaires through entrepreneurial pursuits. In fact, immigrants to the US for instance, are four times more likely to become millionaires than the native population[v]. Ultimately immigrants on average attain a significantly higher net worth than their native counterparts[vi].

A study by Lingxin Hao of Johns Hopkins University[vii] shows that immigrants are financially disadvantaged in their first 14 years as migrants, which is not controversial of course, as migrants take two steps backwards in the hopes of taking three steps forward with substantial outlays such as new property costs, disruption to employment continuity, and physical relocation costs. However, by their 15th year after their migration, they begin to catch up with the net worth of the average native citizen, and by the 24th year as migrants they have in fact surpassed them. This is true in research conducted on migrants of the 1970s and on migrants of the 1990s, even with the latter group’s greater disadvantaged starting position. Ultimately, immigrants landing in their new home will be poorer on average than the average native citizen but by their fifties they will typically be wealthier and more financially independent. This is the Immigrant Paradox.

The lifestyles, behaviours and actions of immigrant groups can therefore serve as education for those looking to further themselves financially, or indeed simply understand how the immigrant couple down the street have retired 15 years earlier than their native neighbours. In fact, there are 10 critical behaviours that act as the blueprint for their financial success, and whilst you cannot or would not want to emulate some of the difficulties they have experienced to get to their relative higher net worth position, everyone can try and emulate those behaviours that have led to their relative success, to a greater or lesser degree.

Most self-help or ‘get rich quick’ books, articles or posts lay down highly unrealistic expectations of people – edicts such as ‘quit your job right now and be an entrepreneur’ are dangerous and irresponsible for the majority of the population. What makes the Immigrant Paradox so appealing is that the actions and activities of immigrants are incredibly risk averse, even their entrepreneurial pursuits are balanced by risk-cushioning savings or a partner in full time salaried employment. This means that the Immigrant Paradox is something that can be followed by everyone and doesn’t require a spectacular leap of faith or a step into the abyss (or indeed a suspension of common sense). What it does need however is exceptional financial discipline, maturity and will power, something that this article will demonstrate that immigrants have in spades.

There are five core reasons why immigrants are richer than you…and here they are:

REASON #1: IMPATIENCE

‘My parents were European immigrants. They came to the States with $1,500, two suitcases, and me, and they managed to build a business, a family, and a future for their family’ – Stana Katic

Stana Katic - Canadian-American actress of Serbian descent (Creative Commons Reuse License)

Immigrant groups have a concept of time that differs considerably from that demonstrated by most other people. The vast majority of immigrants would have felt that their lives had to start over as soon as they had emigrated. Any friends or contacts they would have had would have been left behind, and much of their understanding of how the world worked had to be re-learned as soon as they had landed in their new home. Whereas a teenager born and raised in London, New York or similar would foresee an entire life of opportunity ahead of them, those that emigrated would have left behind perhaps a third or even a half of their lives already and would have to essentially start again.

This would all create an overwhelming feeling that time is running out, and that there is also lost time to make up. Experiencing their new home nation, the immigrant would see more opportunity to progress than they had ever seen in their motherland, and they would be in a rush to make the most of it.

The famous singer of the fifties, Bobby Darin, was born with a serious heart defect and his doctors explained that he would not live to see adulthood. Darin explained how this felt by saying that it was as if he was in a tunnel with a light in the distance and that because he had limited time, he had to run towards the light and not allow anything to get in his way. Talking to various immigrants from various backgrounds, this concept strongly resonates. They are in a rush to make up for lost time, and to do so whilst still young, healthy and mobile.

If you approach life in this way, like you’re in one huge rush to become something, it impacts on how you approach life, business, and money in some very important ways.

Firstly, it inspires a work ethic that is second to none. Many immigrants undertake the worst jobs society has to offer, at the lowest wage, and at the most unsociable hours, as a means to an end, not as a lifestyle choice. To make ends meet and to allow for some savings many immigrant groups will work several jobs concurrently, and many whilst studying too.

Research shows that immigrants work harder than everyone else. British researchers for example, studied official figures on employment and concluded that foreign workers employed in Britain work longer hours than British recruits[viii].

This above average work-rate is also true for second generation immigrants (i.e. native born children of immigrants) and extends to how hard they work academically too; data from the Labor Department’s American Time Use Surveys from 2003 to 2010[ix] shows that teenagers whose parents were immigrants spend the equivalent of 3 hours a week more in educational activities than teenagers whose parents are native born. These additional 3 hours are composed of more time spent at school (about 2 hours more) and more time spent at home studying (about 1 hour more). This was true regardless of ethnicity, but more pronounced in the children of Asian parents.

Working hard, for immigrants, is essentially an investment decision – they forego their leisure time, their days-off, their holiday time, all in exchange for a greater prize in 10, 20, or 30 years’ time. In an age where we are increasingly impatient, where instant gratification is everywhere, this ability to ‘hold’ consistently for decades is incredibly impressive, and absolutely necessary in the immigrant mind to maximise the chance of financial independence and early retirement.

Secondly, if you're in a rush to accumulate money, not only will you be trying to maximise your incoming funds by working hard (often to the extreme), but this would also be mirrored in how you approach your living costs too. Having in most cases lived in relatively humble conditions in their country of birth, trimming back to the bare minimum in their new home to save money would have been entirely possible and, if you’re in a rush to accumulate savings quickly, absolutely necessary. Spending money on non-essentials would represent a deviation or even a betrayal of a grand plan for yourself and your family.

Thirdly, you will look for shortcuts to success. All opportunities will be considered and seized upon with extreme proactivity. This is one of the reasons why entrepreneurship is more commonly found, in percentage terms, amongst immigrants than in native born citizens[x].

Often this overwhelming feeling of needing to make an impact and very, very quickly can make some immigrants financially self-destructive. Speculating on business ideas that then fail is common, but this is seen as just one further obstacle to overcome and they get back to their feet with incredible resilience. If you started with nothing, going back to near-nothing is far less daunting than starting with a lot and having a long way to climb back up if a venture fails. More serious self-destruction is common too – the prevalence of problem gambling amongst various immigrants groups is well documented[xi], and I'm certain that this is in part due to this deep rooted haste, this impatience to accumulate.

Ultimately, most people move at roughly the same speed through life, expending roughly the same levels of energy, and accepting similar voluntary financial set-backs to enjoy the best possible lifestyle. It is no wonder then that most people do not really jump across financial bandings as wealth is a relative concept not an absolute one. Immigrants are however very different; They move much faster and do their utmost to not take any steps backwards financially either. Speed comes with sacrifice, and the willingness to sacrifice in the short-term, for long-term gain is at the heart of why immigrants make more money than those that are not.

This is an economically sound approach. Accumulating savings early in life means that money made early in your life can be put to work to make even more money, and in this regard time is incredibly powerful. By way of example - £1 earned, saved and invested 5 years ago and returning 10% each year, becomes £1.46, which is rather unexciting, but that £1 invested at the same rate of return for 25 years becomes a far more life-changing £9.84. Saving or investing for 5 times longer delivers almost 10 times more return. The numbers are obvious but demonstrate that being sensible with money as early as possible in your life creates serious wealth within a timeframe that will allow you to enjoy it. Knowing this would you have made different buying decisions in your twenties? Quite probably.

REASON #2: DEBT

‘Rather go to bed without dinner than to rise in debt’ – Benjamin Franklin

Most people are indebted to some degree. Immigrants however, with the importance they place on land and property, have it very clear in their minds that there exists what I call two types of debt – active and inactive. Active debt is when you borrow money that is then put to active use making you a financial return. For example, borrowing money that is used to purchase a property to rent out or to start a new business is active debt.

Inactive debt however is when you borrow money and put that money into something that is essentially a liability and will not make you more money over time. Borrowing money to buy a really nice car, or a very large mortgage for a home to live in are common examples, but as is borrowing money to pay for a holiday or to buy a new TV on hire purchase. These are all financial constructions that essentially place a tax on money offered to you.

This inactive debt for the immigrant family is completely contrary to their way of life. If you can't afford it, then you should go without until you've saved enough to buy it, and even then this spend should not slow down longer term financial plans. Many immigrants come from backgrounds where they didn't have luxuries, so going without various things is easier when you move to a more affluent economy.

For those wanting financial success, looking for financial independence, inactive debt is the worst possible thing. Not only are you spending all your money, you're also spending the money that you would have made in the future, as a debt needs to be serviced – it carries interest and continues to place a burden on your ability to pay long into the future. Buying something now, and paying in instalments over time is like a tax on those people that want something today that they simply cannot afford today. We have become averse to sacrifice – whilst the immigrant family comes from a place where sacrifice was a natural and expected part of life, and absolutely necessary to get ahead.

There are exceptions to this of course. In many cases some people cannot avoid taking on inactive debt through severe poverty, or through the need to make ends meet following redundancy, illness, and such like. This is in contrast to those that can't wait another six months to buy that new dishwasher, and instead incur debt to buy one right now, a debt that means the dishwasher effectively costs them at least 20% more than it is worth. The dishwasher is not worth that money, but millions of people do this every day and pay over the odds for things that they really should not buy right away.

A good analogy is building a sand castle, the sand castle being a proxy for wealth and sand being a proxy for money. If you are collecting sand you can build a sand castle. If you collect sand but give it away (i.e. spend it) then you can’t build a sand castle. If you borrow sand from someone else and give it away, but still owe it to the person you borrowed it from, then you are essentially digging a hole - you are in ‘negative sand’, which means you are even further away from having a built sand castle than when you were when you started. The analogy may be a silly one, but it demonstrates that spending decisions aren't about having money or spending money, they are about having, spending, or owing, with the third position being something that most people ignore or aren’t sufficiently concerned by.

Stressing a previous point, the house you live in, with its mortgage, is also inactive debt. Unavoidable of course in that you do need to live somewhere, but that inactive debt shouldn't be bigger than necessary. Many cripple their ability to have disposable, investable funds because they want a bigger house right now. Worse still is renting a property to live in if you don't have to, as whilst not having any mortgage debt, your rental income isn't paying off an asset at all. Renting a home should be seen as a temporary choice until you have accumulated enough to get a mortgage. Immigrants never make this choice as renting the home you live in isn't ownership, and therefore hugely frowned upon; owning land, owning property is the noblest pursuit, not renting it from someone else.

Student debt is also considered by immigrant groups as active debt, but only when it is incurred to gain qualifications in areas that immigrant groups believe provide the capability of paying for itself many times over, i.e. qualifications that can create doctors, lawyers, accountants, and the like. Second generation immigrants typically do well academically, not because they are any smarter than anyone else, but due to the expectations set by first generation parents that make it very clear to their children that they must take advantage of the benefits and opportunities they did not have when they themselves were at their age.

Inactive debt polarises people. Some people view it as a part of life and they use it as and when they please. As long as they can pay their bills and go on holiday once a year, inactive debt is useful, tolerable and indeed for some seen as absolutely necessary. According to the Money Advice Service via an article in The Independent[xii], one million of us will use a payday loan to cover the cost of Christmas while a third of adults will use credit cards. Most immigrant groups find this to be completely ridiculous. Using other people’s money to improve your life today instead of having some patience is deemed as a weakness, and comparable in effect to an addiction to gambling.

Ultimately, immigrants fear inactive debt as for them it holds negative value. Even using an overdraft facility is seen as poor financial control or management. The result of this is that immigrants will typically not spend money on non-essentials until they feel they are financially capable of doing so, and only when they feel they have gained significant financial security. Immigrants are less likely to have credit cards, in contrast to debit cards, less likely to go on holidays they can't afford, and less likely to give their children allowances that aren’t earned. Debt for immigrants is a financial decision not a lifestyle decision.

REASON #3: EDUCATION

‘Yes, many immigrants cherish the value of choice and opportunity and the value of education more than 7th or 8th generation Americans’ – Malcolm Wallop

There seems to be two competing ideas out there when it comes to education and its link to success. The first is that you should do what you love and that success is more likely to then follow, as you’ll approach that discipline with passion and any hard work won’t feel that hard at all. The other is that work is work, and fun and enjoyment aren't the most valuable measures when deciding what you should do for a living. There are extremes here too – the child that is emotionally blackmailed into becoming a doctor as a point of family pride, leading to a successful but miserable work life. Then there’s the 30 year old guitarist who is in a rock band, who absolutely loves it, but only stands a minuscule chance of making any real money from it. We shouldn't begrudge people for choosing what they love versus what pays – its horses for courses – but it’s the immigrant approach to education that helps set them apart financially.

First generation immigrants rarely start rock bands, and they are far less likely to go to acting school, and far less likely to become sports people, as these are considered very high risk career paths, where supply and demand, and the nature of those professions, will mean that only a small percentage will have any real financial success. People pursue those paths because they have a passion, a dream, and it makes them happy. Immigrants, in contrast, feel financial success is more important than fun or enjoyment in the first half of your life. Education is an investment decision, just like working extra hours for them is an investment decision.

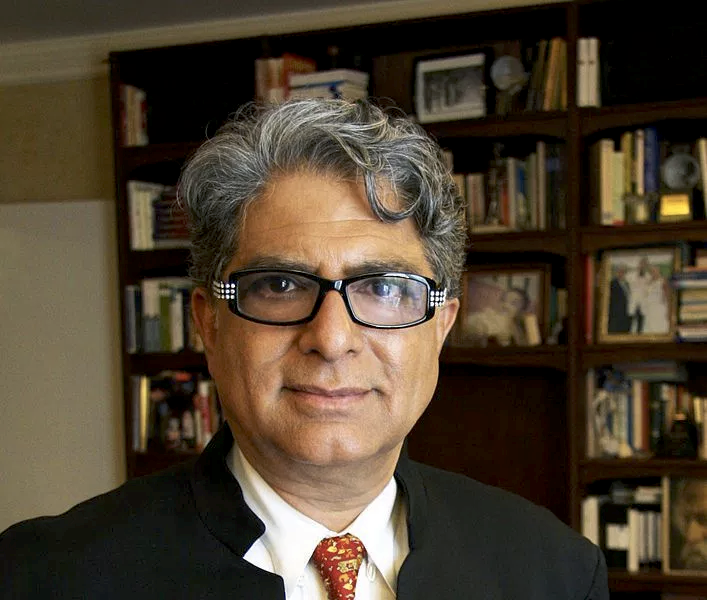

Let’s take the US as an example. Here we find that 64% of Indian Americans had a Bachelor's degree or higher, the highest for all ethnic groups. 60% of them hold management or professional jobs, compared with the US national average of 33%. This contributes to Indian Americans earning the highest average income of all groups in the US, and they also have some of the lowest poverty rates.[xiii]

Deepak Chopra - a well known Indian American medical doctor and author and great example of that high achieving group.

This is not just about Indian Americans though, as migrants as a group are far more successful than their numbers should dictate, and in most areas. For example, over half of all Ph.Ds. in engineering at U.S. institutions in recent years have been immigrants[xiv]. 26% of US based Nobel Prize recipients are immigrants[xv]. Two in five medical scientists, one in five computer specialists, one in four astronomers, and one in six biological scientists are foreign born.[xvi]

This is also not just about the US either. In Germany the academic success of the Vietnamese community has been called "Das Vietnamesische Wunder". ("The Vietnamese Miracle"). A study showed that in the areas of Lichtenberg and Marzahn, the Vietnamese account for only 2% of the population, but make up 17% of the prep school population.[xvii]

This focus on what pays unsurprisingly results in higher earnings - median household income of Asian Americans in the US is $68,780, higher than the total population's $50,221.[xviii]

Education has a clear and direct correlation with earning potential, assuming that the education is something that can be applied to a real, professional pursuit – we're talking medicine, engineering, computing, etc. In an environment where everyone has a degree and many graduates are out of work, education should not be discarded as a waste of time. Training and qualifications in the right areas will absolutely mean you make more money, it’s then what you do with that money that makes the decisive difference to your ultimate wealth in the second half of your adult life, and invariably what your children inherit or not.

Education is an investment decision for immigrants, not a lifestyle choice.

The investment does pay off. The numbers suggest that someone with an education in something deemed useful by the immigrant mind delivers a 35% greater salary, which is the equivalent to something like $740,000 more in a working lifetime than without. Taking out a heuristic tax sum, that’s an additional $500,000 or so for retirement, or a funding level that can be invested or used for entrepreneurial pursuits, which would double that $500,000.

Even taking a reasonable amount for student loans into account does not alter this huge number. If teenagers knew that their 4 years in university would yield them $1m at the age of 50, would they chose a different subject, study harder, take things more seriously? They should. Again, if you want wealth, then you must approach education as an investment decision.

REASON #4: SELF-BELIEF

‘It has given me a global vantage point, being the daughter of immigrants from China, who had nothing when they came here. And now I am leading a company. It speaks to something deep in me, the concept that you don’t have to start with anything’ – Andrea Jung

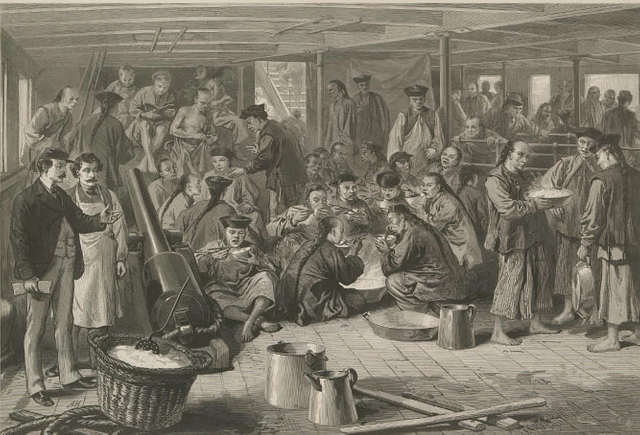

Chinese emigration to America: sketch on board the steam-ship Alaska, bound for San Francisco

Immigrants emigrate to succeed. For most this is an active decision – I'm going to go over there where there’s more opportunity than here, which I will seize with both hands and make something of my life. It’s the first decision that dictates most others thereafter. That initial decision is like an electrical charge that propels them forward, in a particular direction, and at considerable speed.

This electrical charge takes place less frequently within native populations as they are born into a pace of life that has existed for generations in their own families, which then becomes their pace of life. People will often follow the template set by their parents, however poor that template might be. For native populations there is essentially no major trauma, like emigrating, to make them change lanes from following the course set at their birth, to move across the central reservation with a dramatically different view of their own mobility.

Immigrant communities believe that they are on an upward trajectory the moment they land in their new home. They made a giant leap to a world of opportunity and believe that they've been given the best chance possible to succeed. They value the opportunity because they never had one as good. They believe that their mobility across geographical lines extends to the potential to be mobile across financial classes too. They’re not part of an existing class structure so are not restricted by the ‘psychic prison’ that this often creates for native populations.

In many native populations it’s quite different, particularly amongst the traditional working and lower middle classes. There is an expectation that each generation continues in the vein of the one previous. It is very common for instance for job roles to be passed down from father to son, mother to daughter. Long lines of carpenters, gas engineers, plumbers, market traders, exist, as do long lines of apathy and criminal endeavour too. This extends to professional services too of course – doctors tend to exist in differing generations of the same family far more than the statistical average. It isn’t therefore about capability as much as it is people believing that they can do something and then being given the support structure to achieve it. Poverty for example becomes reinforcing – a damaging approach to indebtedness is passed down, community and family pressure to not move away from the herd, and the belief that you have a place in society and it’s impossible to move beyond it as much as you might desire it, so why try?

This is acute in the UK where a class structure still exists, at least in the collective mind. US purists will claim that class doesn't exist in their republic – not true – people there still largely self-select job roles that they believe society has made available to them. Black children believe they can be boxers, Jewish children rarely become sports men and women, working class kids should work with their hands, men should not be nurses, etc. These are the result not of capability, genes, or ethnicity, but of the psychic prisons passed down to people by parents or delivered by the media, the government, and religion. It’s what restricts people from believing that they have mobility.

Immigrants don’t suffer as much from these debilitating psychic prisons, as they have actively broken ties with their past and the power structures they knew and understood, and those that dictated their place in society. They don’t fit into the class structure that their new home has solidified over hundreds or thousands of years so for them it doesn’t exist and they define their own. Whilst they may arrive very poor, they would not put themselves into that social category – if anything they are noble peasantry and only poor because of the poverty of where they came from, not because they shouldn’t be wealthier. Most retain a national and religious loyalty, but very few maintain any restriction on themselves or their children that is based on history, class, or regional expectation. Genuinely thinking and believing that you could make millions of dollars or pounds is a very powerful mind-set and provides motivation, focus, and belligerence.

A case in point - according to the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, immigrants to the U.S. start businesses at a rate of 62 per 10,000 people, compared with a rate of 28 per 10,000 for native-born Americans. More than half of those foreign-born founders came to the US to study[xix]. According to a peer-reviewed study pulled data from three large, nationally representative government data sets, issued under the auspices of the U.S. Small Business Administration, immigrants are almost 30 percent more likely to launch a business than non-immigrants. According to the study, roughly 16.7 percent of all new business owners in the US are immigrants, yet immigrants make up only 12.2 percent of the workforce there.

Yes another study, released by Duke University and UC-Berkley, found that immigrant entrepreneurs founded 25.3 percent of all U.S. engineering and technology companies established in the past decade. This is very significant, since immigrants make up only 11.9 percent of the entire U.S. population[xx]. In every 10-year census from 1880 to 2000, the percentage of immigrants who are self-employed is higher than the percentage of natives who are self-employed[xxi].

40% of the Fortune 500 in the US were founded by immigrants. Immigrants are “much more likely to launch a high-tech startup, compared with their native born peers”[xxii]

This also cuts across gender lines too. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, immigrant women were more likely to be business owners when compared to native-born women. Census data shows that 8.3 percent of employed immigrant women were business owners, compared to 6.2 percent of employed native-born women.

Immigrant women are more likely than U.S.-born women to be business owners. In general, women have made modest progress since 1990 toward closing the gender gap in business ownership, with immigrant women leading the way[xxiii].

One final statistic - research on entrepreneurship also shows a higher rate of entrepreneurship among children of immigrants, than children of native-born Americans[xxiv].

There are clearly therefore a collection of attributes or experiences that make immigrants more likely to be entrepreneurial, and by extension more likely to achieve significantly more financially than a native-born person.

REASON #5: LONG-TERM INVESTMENTS

‘They were immigrants, they had no money. My dad wore the same pair of shoes, I had some ugly clothes growing up, and I never had any privileges’ – Amy Chua

Amy Chua is a Chinese American lawyer, writer, and legal scholar. Image credit: Larry D. Moore CC BY-SA 3.0.

From the bulk buying of essentials to plastic wrapping furniture to keep it newer for longer, the immigrant family can appear to outsiders as spendthrift and even miserly. Whilst these traits remain with the immigrant for his or her entire life, they are most pronounced in the first 10 years as migrants. This 10 year sacrifice makes the real difference to their ultimate wealth because they can save more of their income early in their lives. Research shows that migrant households have a consistently higher propensity to save than native born households[xxv] and it means they become homeowners earlier. Immigrants for instance make up just 16% of the US population but are expected to make up 35.7% of homeowners by 2020[xxvi].

With their higher savings rate, they become homeowners earlier, and throw off the routinely underestimated shackles of mortgage debt, giving them more disposable income thereafter to pursue other wealth strategies, principally via rental properties or their own businesses.

Many first generation immigrants have a concept of land and its importance that differs from what we're familiar with in the affluent West. Some would have come from countries where people fought in their lifetimes over borders, land and property. And this isn't people fighting in courts, we're talking about people fighting with weapons and killing each other. In many cases it is that fighting that forced or compelled them to emigrate to more stable lands to begin with. If you've witnessed people fighting over the land that your family had owned for 500 years, you will quite naturally consider it the most valuable thing in the world.

Most would also have come from families where land, not Tesco or Walmart, fed the family. Your trees, vegetable patches, and your physical exertion to maintain the productivity of that land, would have given you a connection to it, as an enduring symbol and concept, that we have long lost as committed urbanites.

Land was also the main source of wealth and respect in many of the countries where immigrants had come from. Even today in many parts of the world, your power in a region isn't about how much money you have, but how many acres you hold. And if you hold lots of land, you can produce a surplus of fruit, vegetables, and more, sell these in markets, and make lots of money. Land was perhaps the only route to making money in most of those parts of the world. If you had no land in your native country, or had lost it through war, poor financial management, or something else, then you’d see serious poverty.

Land therefore is a concept for first generation immigrants that holds immense emotional, practical, and cultural power. The Greeks have a phrase – “if you fall, take hold of the land to get back up”, i.e. only land is reliable, only land can provide support. As a 2nd generation British Greek Cypriot born and raised in London, this was something that I was told by my father once a year at the very least, and even now that I own considerable amounts, he still insists on telling me this. His father told him the same, as did his father’s father, and so on and so forth. This is a great example of how the cultural perspectives of a first generation immigrant group are indoctrinated into the second. It weakens as generations come and go, but is immensely strong in both the 1st and 2nd generations.

Once someone has emigrated from a relatively rural existence to a job-rich urban jungle, property becomes synonymous with the old concept of land. Getting on the property ladder early is therefore incredibly important, as is getting on the rental property ladder. In the same way as land produced value in the motherland through its production of fruit and vegetables, or to raise animals, property would absolutely need to produce value too. Building a portfolio of rental properties therefore becomes the principal objective of many immigrant groups. It is common for immigrant groups to initially live in properties far less impressive than their purchasing power would allow, as their funds go to building their portfolio, and not paying more than necessary for the house they live in, which is essentially treated as a liability.

Getting on the property ladder early is an absolute priority that surpasses all others for most immigrant families. This is why it is often the case that immigrant homeowners are disproportionately younger compared to native born[xxvii].

Once they are on the property ladder, they then very quickly get on the rental property ladder. This is why the asset in which immigrants have the larger percentage of total liabilities in comparison to native citizens is in property, excluding the home they live in[xxviii]. When comparing the debt of immigrants to that of native populations, you need to compare apples with apples. Immigrant debt is active debt in rental property.

Getting on the rental property ladder is also of critical important for immigrants as it is one of their main methods of generating real, lasting wealth and, not insignificantly, it does not require any skills that would restrict them from doing so. For immigrants owning a property within 25 years that has been paid for by rental income is too good a deal to refuse, even if that means sacrificing your quality of life today to accumulate enough to pay the deposit.

Owning your first property before 40 or even 30 years of age is certainly a challenge but it is achievable. As a first generation immigrant it requires working far more hours than the average person, and spending as little as is humanly possible. It may also require the pooling of money with a sibling or personal or professional partner.

Property therefore is the principal building block for successful immigrant families to build financial independence. They have far less of an affinity or love for stocks and shares, funds and the like. Property for them is tangible, provides almost guaranteed long terms gains, and doesn't require them to have mastered any particular trade or achieve any qualification to understand and exploit.

It’s worth noting that whilst getting on the rental property from a relative young age is often key to immigrant wealth accumulation, it is also possible for anyone to start later and simply put down larger deposits to expedite your complete ownership of those properties by an age at which you can genuinely enjoy the rewards. However, it is much easier to sacrifice non-essential spending when you are younger, and particularly before you have a family to prioritise over all else. It’s also much harder to work longer hours with a family at home waiting for you. As Francis Bacon once said ‘He that hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune’, and there is indeed some truth in that.

In conclusion

Much of this article has been concerned with the decisions people make in the first half of their lives, and how those decisions impact on their financial positions in the second half. Immigrants’ decisions on where they apply their energies early in life are framed as investment decisions, whilst native born citizens tend to think of most decisions are lifestyle decisions. From how they approach debt, to how hard they work, to how they spend their money, every decision is an investment one in the truest sense – what am I going to get back in 20 years’ time based on this decision? It’s ultimately about will power, sacrifice, and playing the long game. If you understood this as a teenager would you have made different decisions? That’s the real million dollar question.

REFERENCES

[i] 40 percent of the nation's Ph.D. scientists and engineers were born in another country - http://www.neighborhood-centers.org/en-us/content/Myths+versus+Facts.aspx

[ii] Immigrants, Integration and Cities: Exploring the Links By OECD (ISBN-10: 926416068X)

[iii] Immigrants, Integration and Cities: Exploring the Links By OECD (ISBN-10: 926416068X)

[iv] foreign-born entrepreneurs have been behind 25 percent of all U.S. technology startups over the past 10 years, according to research at Duke University - http://www.neighborhood-centers.org/en-us/content/Myths+versus+Facts.aspx

[v] The American Dream: From an Indian Heart by Krish Dhanam (ISBN-10: 1618976710)

[vi] How do Immigrants Fare in Retirement?, Purvi Sevak, Department of Economics, Hunter College, February 2013 - http://web.williams.edu/Economics/wp/sevak_schmidt_feb2013_ssb.pdf

[vii] http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.197.4514&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[xi] (Blaszczynski (1995); Coman, Burrows & Evans, 1997; Trevorrow & Moore (1998); Hallebone (1999); Lesieur & Rosenthal (1991), Grant & Kim (2002); Carroll & Huxley (1994); Blaszczynski, McConaghy & Frankova, (1990). Ohtsuka, Bruton, Delca and Louisa (1997)

[xiv] http://www.forbes.com/sites/georgeanders/2012/05/09/why-immigrants/

[xvi] http://www.neighborhood-centers.org/en-us/content/Myths+versus+Facts.aspx

[xvii] Von Berg, Stefan; Darnstädt, Thomas; Elger, Katrin; Hammerstein, Konstantin von; Hornig, Frank; Wensierski, Peter: "Politik der Vermeidung". Spiegel.

[xviii] http://blog.chron.com/insidepolicy/2011/05/asian-american-population/

[xix] http://www.kauffman.org/Details.aspx%5C?id=1508

[xxii] http://www.forbes.com/sites/georgeanders/2012/05/09/why-immigrants/

[xxiii] http://www.fiscalpolicy.org/FPI-release-immigrant-small-business-owners-20120614.pdf

[xxv] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1475-4932.12000/full

[xxvi] http://www.dailycal.org/2013/09/03/immigrants-are-more-than-entrepreneurs/

[xxvii] http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/immigrant_remodeling_september2009.pdf

[xxviii] Sanders and Nee 1993; Portes and Rumbout 1996, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.197.4514&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Nice post , I have ReSteem so that more ppl will get to read it.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://andreaspouros.com/2015/02/08/the-immigrant-paradox/

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

For an immigrant to get here they have to have a lot of money. Since they have money they will be likely to be secessful. I know you said that but I think it is the most probable solution.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @andreaspouros! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit