This week we @phillyhistory are faced with the hypothetical challenge of dispensing $10,000; $100,000; $1,000,000; and $10,000,000 to have maximum impact for public history. Here is my idea.

Microgrants

A microgrant is a small grant $2,000-10,000 to an individual or community organization for impact oriented project based on the model of microfinance pioneered by nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus through Grameen Bank in Bangladesh.

Unlike much of microfinance and microcredit, microgrants need not be repayed in money, but rather through the production of public history.

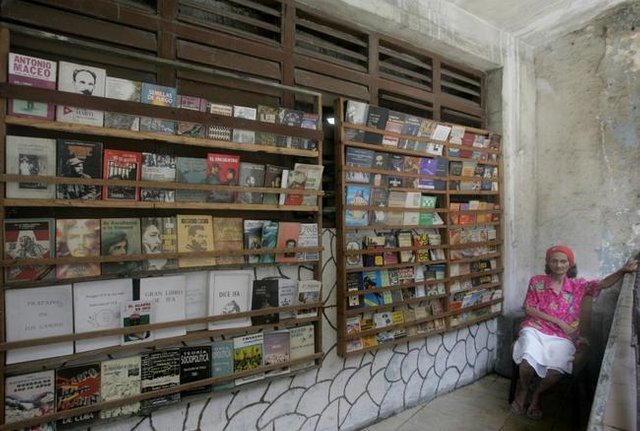

A microgrant could power the regeneration of historical production in places long detached from major corporations and cities. Prospective award recipients might team up with studies like this one - image source that show there is literature beyond the city.

How this works

Depending on the size of the money available, an announcement would be sent out to public historians across the globe for prizes of various sizes- none greater than $10,000. That means if $10,000,000 was available for public history, ONE-THOUSAND promising projects would get $10,000 to bring public history to the world.

If a smaller amount of money was available, like $10,000, the prizes would be split into fifty prizes of $200.

The goal is to give as many public historians as possible a voice, with emphasis on developing nations and often ignored public histories.

The Selection Process

Selecting between fifty and one-thousand winners is no small task. That is why the selection process would be run by an organization like Spark who have experience with the use of microgrants in developing nations. Spark uses a locals-know-best approach where the grant winners are given freedom to use the grants how they see fit. Whereas a podcast might be the most useful way to reach an audience in the United States, using the grant for a public history project in Cuba might take a different form like radio or literature.

Another potential method of the selection process is teaming up with an organization like the Peace Corps, who are currently active in 65 nations. Through these connections, grants could be selected, administered, and reported-on after completion.

Finally, a call for applications online, while it might limit applicants, would still open the door to a world full of ideas and present a more manageable method of grant dispersal.

Potential Problems, Prospective Solutions

You might be worried that $200 is not enough to make a significant contribution to public history. For public history in the United States, you might be correct. However, at an average monthly salary of $30 a month, Cubans would benefit greatly from such grants. A major issue in developing nations is that the public history, literature, and art is produced solely by the wealthiest citizens in the capital cities. However, microgrants would enable public historians to produce works away from the publishers and cities that dominate the established market. Rather than having another story published about the history of Havana, a city romanticized and fetishized by historians local and abroad, a microgrant would bring to light the public history of towns like Gibara, long forgotten after the departure of American multinational sugar companies.

CinePobre, originally in Gibara, has grown in fame recently under the framework "that film becomes art only when its materials are as inexpensive as pencil & paper. Cine Pobre Film Festival is the 100% cartel-free intersection of culture and capabilities." It is just one example of how microgrants could change public history.

Small grants won't only work in the developing world. With the proliferation of technology, a grant of two-hundred dollars could make the difference between quality recording and noisy nonsense in a burgeoning podcast. From personal experience, I know my podcast, Hour of History, could turn two-hundred dollars into equipment that professionalizes the sound and closes the gap between professionally produced media and the realities that public historians often have to contend with.

Havana is beautiful and full of history, but places away from the city need only small grants to share their equally rich history.

Havana is beautiful and full of history, but places away from the city need only small grants to share their equally rich history.

Discussion

Is this the most democratic stewardship of money to improve public history?

Is it too small to make a meaningful impact?

Do we need more oversight in grant-giving and award monitoring?

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.

Very interesting idea.

Unclear, though, how would it be implemented. What would the process and cost be? Would Steemit be a good platform for both payment and delivery of content?

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

This is a great idea and I could see developing a model based off of crowdfunding platforms like Kiva (except grants, not loans) and Donors Choose!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @hourofhistory! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @hourofhistory! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit