How a transformative approach to collaboration and finance

supports citizens, governments, corporations, and civil society to

share the burdens and the benefits of solving wicked problems.

CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Notes

1.3 Glossary

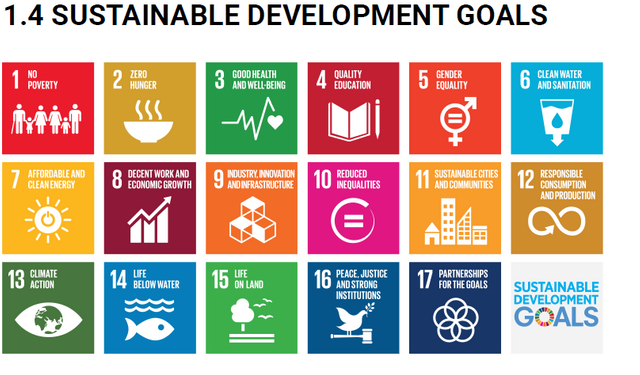

1.4 Sustainable Development Goals - OPPORTUNITY

- CHALLENGE

3.1 Challenge

3.2 Undue Influence

3.3 Observable Patterns

3.4 Dysfunctional Systems

3.5 Dysfunctional Data

3.5.1 Siloed Data

3.5.2 Fragmented Data

3.5.3 Inaccurate Data

3.5.4 Ineffective Data Flows

3.5.5 Simple User Flow

3.5.6 Simple Data Flow

3.5.7 Universal Data Flows

3.5.8 Data Fragmentation

3.6 Misaligned Capital

3.6.1 Ineffective Capital

6.2.1 Citizens

6.2.2 Communities

6.2.3 Capital

6.2.4 Sectors

6.2.5 Functions

6.2.6 Mechanisms

6.2.7 Markets

6.2.8 Market Network

6.2.9 Mechanics

6.2.10 Requirements

6.3 Logical Design

6.3.1 Logical Design Elements

6.3.2 Data Classification Sample

6.3.3 Sample Logic Flow

6.3.4 Simple Data Flow

6.4 Physical Design

6.4.1 Physical Design Elements

6.4.2 Physical Design Descriptions

6.5 Market Network Prototype - CONCLUSION

7.1 Conclusion

7.2 Get Involved

7.3 Further Research

7.4 Authors

3.6.2 Myopic Capital

3.6.3 Replication of Diligence

3.7 Flawed Decisions - INNOVATION

4.1 Innovation

4.2 Social

4.3 Financial

4.4 Legal

4.5 Technical - SOCIAL EQUITY

5.1 Transforming Social Finance

5.1.1 Monetise the Problems

5.1.2 Align Diverse Stakeholders

5.1.3 Detour: Putting the Social Back in SIBs

5.1.4 Focus on Outcomes Over Outputs

5.1.5 Create Social Equities

5.1.6 Embed Finance in a Larger System - SYSTEMS DESIGN

6.1 Systems Design

6.2 Architectural Design

Each year hundreds of millions of people work in tens of millions of organisations, and

deploy trillions of dollars in an effort to solve the most pressing challenges of our

time.

Yet despite this vast commitment there remains an estimated $50 trillion funding gap

required to address the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, or Global Goals) - the

most comprehensive, cohesive and coherent description of these wicked problems to

date.

The existing approach presumes that a multitude of entities addressing some part of

the greater challenge will, without appropriate incentives and mechanisms, selforganise

themselves into an effective, efficient, and scalable solution. This is

dangerously and wilfully naive. By comparison, the International Space Station (ISS),

the largest multi-lateral project, and the single most expensive construction project in

history, came at an estimated cost of only $150 billion. The ISS would never have been

launched without clearly defined incentives, and a coordinated pathway to success -

so what makes governments, corporations, and civil society actors believe they can

solve trillion dollar problems through a piecemeal, incremental approach?

Over the past three years we have consulted with many of the world’s largest and

most active public and private institutions that are deploying significant levels of

capital towards the resolution of the Global Goals. Without exception, while those

we’ve connected with all consider the resolution of the SDGs to be a moral imperative,

none of them genuinely believe that the Global Goals will be achieved by 2030.

We beg to differ.

On the face of it, the bottom line is depressingly simple - there is no single entity with

either the cash or the capacity to invest or deploy the requisite capital to achieve one,

let alone all, of the Global Goals. And there are currently no incentives rewarding

outcome over effort, or mechanisms for collaboration at the scale necessary to

actually solve the SDGs.

In that challenge also lies the opportunity: the constellation of entities working to

address these issues require financial incentives, operational infrastructure, and no

small measure of humility, to transition from organisation-centric behaviour, to

mission-centric behaviour.

From our perspective, this is the only way in which human society can move from

treating the acute problems the SDGs represent, towards the systemic resolution of

the underlying chronic issues.

We believe that not only can the SDGs be solved by 2030, but that it is the single

greatest moral imperative of our time that they must. Further, we believe that the

primary impediment to their resolution is rooted not solely in resources, technology, or

intent, but primarily in a combination of ineffective systems design, and intransigent

human behaviour driven by short-termism, fragmentation, and counterproductive

incentives.

What follows is the distillation of decades of combined thinking and acting in service

to global change. Rooted in both philosophy and practice, this document is a roadmap

we are already executing against. Our execution partners are organisations that agree

that global infrastructure is the missing element necessary for not only the resolution

of the Global Goals, but for each successive wave of global issues that humans will

continue to face as we continue to evolve.

4

Cameron Burgess, Astrid Scholz, Arthur Wood & Audrey Selian

San Francisco, CA | Portland, OR | Geneva, Switzerland

1.2 NOTES

Billions to Trillions is less of a white paper, and more of a roadmap. It articulates

and builds upon concepts and perspectives developed by a vast network of

individuals and organisations.

We have not thoroughly footnoted this document, as we are not so much seeking

to make an argument, as to issue an invitation.

Our intention is to stimulate action, and as such we welcome the opportunity to

discuss the contents in order that these ideas may be further refined in service to

the common good.

This document pays particularly close attention to digital technologies and

systems — not because we believe that technology in itself is a silver bullet, but

because it is the foundational infrastructure necessary for mobilising all forms of

capital at scale. A theory of change that cannot be executed against is a fantasy,

and we are nothing if not pragmatic.

Of note is our use of the catch-all ‘world-positive’ to describe the constellation of

individuals, organisations, and networks who are working for the common good.

We reject the false-dichotomy of non-profit and for-profit, and further reject the

way in which the various players in this space are separated by who they serve,

and how they serve them.

1.3 GLOSSARY

One of the greatest challenges in developing documentation is the proliferation of

terms, acronyms, and internal ‘short hand’ we use to describe our work, much of

which has divergent meaning.

Countries, cultures and contexts all determine our use of language, and so, for the

purpose of this document, we considered it essential to define in advance what

we mean in our use of some terms.

Of specific note is that we are using the United Nations’ Sustainable Development

Goals solely as an organising principle for wicked problems. That is not to say that

this work is focused exclusively on the Global Goals, simply that they represent a

near term opportunity for global coherence amongst world-positive people and

projects.

A clickable chart of these goals, with links to their descriptions on the United

Nations website, appears on the next page.

2.1 OPPORTUNITY

The business of change is the biggest business there is.

Solving trillion dollar problems is not achievable by any one entity in isolation,

however. As such, the opportunity is for all citizens, across all sectors, engaging in

any behaviour that contributes to measurable and often monetisable beneficial

outcomes, to:

A. participate in the funding, design and deployment of core infrastructure.

B. connect their current digital systems to backbone systems such that the value

they already hold may be more effectively mobilised, and compensated.

C. be appropriately compensated for the value they create

Our model combines outcome based financing - a methodology by which funders

fund on the basis of success - with the financial, legal, and technical structures to

incentivise and operationalise collaboration at an unprecedented scale.

The core question we are answering is:

What could be not only more urgent, but more

rewarding, than solving the greatest challenges of

the 21st century?

3.1 CHALLENGE

The core of the challenge is simple. Despite their commitment to change, most worldpositive

entities are either unable or unwilling to move beyond competition, or simple

collaboration, in order to mobilise capital at the scale, and with the speed necessary,

to solve wicked problems.

Over time this has resulted in the mass proliferation of parallel organisations,

networks and initiatives that are frequently cited as evidence of ever increasing

market demand for world-positive solutions.

Unfortunately, despite the best of intentions, each new venture spawns a new set of

operational systems, and inevitably becomes constrained by organisational thinking,

jargon and process. As much as these entities may intend to support the resolution of

a mission larger than their own, they are often functionally unable to do so.

Further, the normative behaviours of markets have become the modus operandi for

any venture seeking to catalyse beneficial change. Through individual, organisational

and social spheres, we have become ensnared in Industrial Age metaphors, models

and missions, failing to recognise that our relative affluence and privilege is rooted in

an extractive economic system that is fundamentally unsustainable, and hence

antithetical to our ongoing ‘success’ or ‘progress’.

Funders of change are complicit in this state of affairs, rewarding novelty over utility,

competition over collaboration, and outputs over outcomes. This is further

exacerbated in philanthropy by the prevailing ‘two pocket thinking’ that typically

allocates 5% of capital to making world-positive change, while the other 95% remains

invested in the industries and practices that produced the problems we face in the

first place. We expand on the challenges exacerbated by the ‘golden herd’ on p. 12.

3.2 UNDUE INFLUENCE

While philanthropic capital is patently insufficient for achieving the SDGs, it is

nonetheless disproportionately influential in shaping how we go about addressing

wicked problems.

Networks of the richest and most influential funders and philanthropists tend to move

in ‘golden’ herds. The core differentiation between them lies in their idiosyncratic

networks of influence, and choices of the geographies and sectors in which they

operate, with brands often expressed in terms of the ‘theory of change’ against which

investments are made.

Those with the biggest brands and banners tend to set the development agenda in any

given sector. They provide the ecosystem gestalt, around which smaller entities

manoeuvre to either position themselves in partnerships for co-programming or cofunding,

or as direct recipients of capital in exchange for program execution services.

Typically these services are transacted on a the basis of efforts undertaken to achieve

an intended change according to the funder’s ‘logic model’, rather than an outcome

model where verified success is rewarded.

Unfortunately, philanthropists and foundations are ultimately answerable to no-one —

their results are as transparent or opaque as they choose to make them, and while

they ostensibly serve the public good, they are not governed by the public in the public

interest.

Financial capital is not, and should not be, the the sole determinant of influence in

addressing wicked problems. Neither should political capital. While there is no

denying the power of the intention and intellect these individuals and organisations

bring to bear on wicked problems, there is also no denying that the wealthy are not

imbued with superpowers.

Equating position, financial wealth, education, or convening power with the knowledge

of how best to address wicked problems is fundamentally the same thinking as that

which has created (and reinforced) the inequities of neoliberal economics.

If our current development wisdom is one that simply reinforces the status quo, and

ignores solutions that incorporate the knowledge and incentives of the affected

citizens, or ‘beneficiaries’ in the parlance of philanthropy, we unintentionally

perpetuate the extractive status quo.

By imbuing major foundations and philanthropists with unearned privilege and

unilateral influence on what is ‘important’, we unintentionally perpetuate the top down,

extractive nature of these interventions, as distinct to working on a basis of merit,

innovation, and above all, the cooperative logic that drives any successful endeavour.

The disclosures and transparency which form the very essence of being ‘public’ for a

company, are the same essential ingredients necessary to support responsibility and

efficiency in a global development marketplace where trillions of dollars are spent

each year on millions of service providers.

The bad habits we diagnosed previously are exacerbated by the habits of the golden

herd. Together, they result in a development industry marred by high operating

overheads and business model inefficiencies, market externalities and distortions, and

lack of transparency.

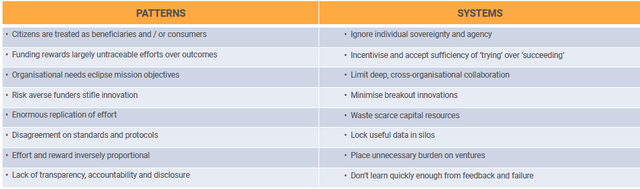

The resulting patterns (see over) have shaped

systems that serve neither people nor planet as

well as they could.

3.3 OBSERVABLE PATTERNS

Creating world-positive solutions at the scale required represents a great many

challenges. As impact investors, technologists, and systems-thinkers, we see

these challenges manifesting directly in the information systems and tools

(financial, legal, and social) that we use to conceptualise and operationalise the

3.4 DYSFUNCTIONAL SYSTEMS

As the previous slide indicates, scaling solutions to wicked problems is adversely

impacted by systems that have not been deliberately designed for this purpose.

These systems can be essentially broken down into three primary areas:

Social Systems

The patterned network of relationships constituting a coherent whole that exist

between individuals, groups, and institutions.

Technical Systems

The hardware, software, algorithms and processes that facilitate the storage and

transaction of data

Capital Systems

The instruments created for the purpose of valuing, storing and transacting capital

While there is no denying the impacts our social systems - informed by our values,

beliefs and behaviours - have upon systems design, the purpose of this document is

primarily on the latter two.

Frankly, our experience has been that, when confronted with the inconsistency

between their values and behaviours, most people opt to change their behaviour.

Repairing and redesigning the underlying technical and capital systems is no small

task - yet it is made substantially easier when we align on the importance of solving

the problem, as distinct to being the ones to solve it.