Both readings for this week, though written over ten years apart, grapple with very similar issues plaguing the world of history institutions. Failure to communicate; unwieldy collections; an inability to respond to increasing technological advances—The list goes on and on. To address these problems, one reading advocates for a History Center and the other a History System. Collaboration and communication are central to both potential solutions, but inexplicably, the public does not seem to be even a hypothetical part of the conversation.

I find it strange that the public should come second in discussions of public history. For example, let’s take a look at what each reading deems the ideal mission for a public history institution:

“The History Center will address the pressing need for a single, strong, highly visible institution that collects, preserves, interprets, and makes accessible the full range of Philadelphia’s rich historical holdings.”

“to preserve, make accessible, and interpret collections that relate to the history of the United States; and to engage a wide range of audiences to communicate the ideas and stories that illuminate history.”

.jpg)

In both of these mission statements, collection and preservation take precedence over accessibility for the public. The emphasis seems to be on the artifacts and caretakers rather than the people who attend museums and libraries. In a continual search for relevance, these institutions contract consultants for thousands of dollars, but those consultants (the TDC group, to be more specific) want to keep the conversation on the “inside.” The TDC’s History System proposal aims to foster much needed communication between Philadelphia’s nonprofit history institutions; however, the insular approach prioritizes solutions proposed by “funders and other sector-wide supporting institutions.”

In addition to insularity, the History Center proposed in 1996 also glorifies history’s privatization. Faced with a moratorium on city funding for the Atwater Kent Museum (now the Philadelphia History Museum), the organization behind the History Center wished to merge the PHM collections with the artifact collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. This History Center would also have exhibit space for other failing institutions to present their collections. However, the proposal fails to address why audience numbers or member subscriptions had fallen at these other institutions and how the History Center’s visitor numbers would be different. They found a solution to keep all the stuff, but I do not see a solution as to how to keep people coming through the doors.

How would you rethink the priorities of our cultural institutions? How could we best rewrite these proposed mission statements above?

Sources:

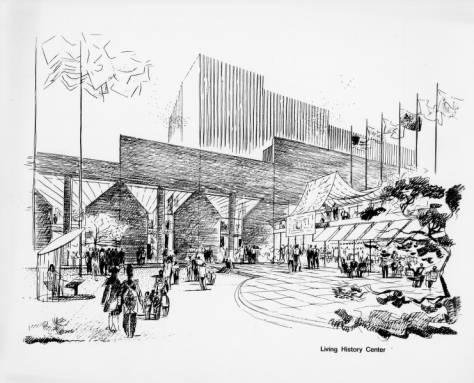

Architectural Plans for Philadelphia's Living History Center, 1974. Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center; George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection.

Building a Sustainable Future for History Institutions: A Systemic Approach (TDC: Boston, MA: 2009)

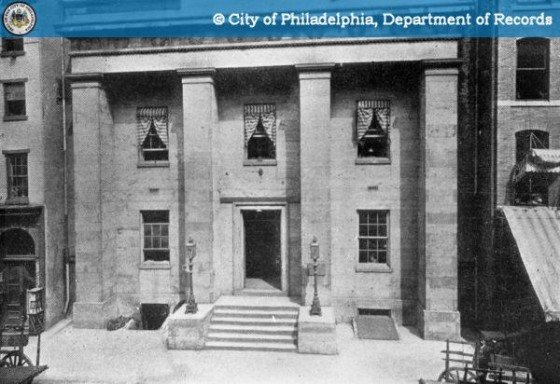

Franklin Institute, 1895. City of Philadelphia, Department of Records.

The Vision for a History Center in Philadelphia, 1996.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

This is a really poignant hole missing in these pieces, and I also see a lot of parallels between this post and @cheider's post about the 1892 art exhibit that dared to make itself accessible to those outside of the upper class.

We say we're in the field of public history but in a way we haven't moved further beyond the time when museums were largely private exhibitions meant for an exclusive few. We can talk a big game and make moves like decreasing admission or engaging in outreach but museums can't become truly accessible until this mindset changes and we prioritize our audience.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Yea, every time we read something by one of these consulting firms, I'm like, "But this isn't what I learned in school? Is this the field we're walking into?" It makes me feel super naive and youthfully ignorant, but I guess it's good that we're getting a firm grasp of how large and established institutions view their public.

I'm definitely headed over to read @cheider's thoughts now! Also, thank you for this glorious Michelle Buteau gif. My Steemit blog has been blessed :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

You rightly point out that “collaboration and communication are central to both potential solutions.” To frame it more broadly, both point to connectivity which seems to be undervalued and underutilized. I have wondered if a commitment to connectivity isn’t interpreted as a threat. After all, TDC’s version of a History System, which would thrive on new connective energy, also downplays and possibly denies the older, established opposite - decentralization or fragmentation - which is key to that system.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I'm not sure I totally understand what your comment means, @kenfinkel! I will definitely be asking you to elaborate in class, and then we can post some clarification here.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit