This is a repost of https://www.creativecoin.xyz/classical-music/@partitura/german-organ-tablature-explained-part-1

In the comments @organduo suggested the article might be interesting for the stemgeeks-community as well. It is not a really scientific article, but it reflects the results of my own research how to translate German organ tablature in modern music notation.

I'll publish the second part shortly. Le me know if this first part conflicts with the guidelines of the stemgeeks-community. Then I'll exclude it from the publication of the second part.

German organ tablature is a music notation system, widely used in Northern Germany from roughly 1450 till early in the eighteenth century. It was primarily used to notate keyboard music, like harpsichord music and (now here comes a surprise...) organ music. The music of for example an important composer of organ music, Dietrich Buxtehude, survives mainly in manuscripts written in German organ tablature. Even some of Bach's autographs are written in organ tablature (part of the Orgelbüchlein and the Fantasia BWV 1121). Anyone who wants to play keyboard from (early) German Baroque manuscripts, or who wants to publish them in modern notation (like me), has to learn how to decipher this, on first sight, somewhat mysterious music notation system.

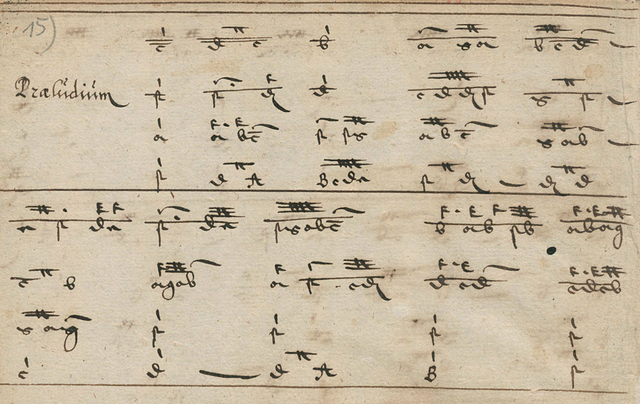

Here is an example of what German organ tablature looks like:

For years I have wondered how this Chinese like script could represent music. Looking for new sources for music to publish I quickly skipped manuscripts written in organ tablature because they were unreadable for me. As I consider myself a good musician (cough, cough) it irritated me a bit that I could not read music from the style and period I play the most. So, I decided to learn to decipher manuscripts written in German organ tablature.

The biggest surprise: it's not difficult at all. It's actually very easy once you understand the basics of it. You don't have to be a scholar, trained in arcane scripts, to learn to read it as well. With a bit of practice one can even learn to play directly from music notated in organ tablature. Well, that should actually not be a surprise as organists have played from this notation system for hundreds of years.

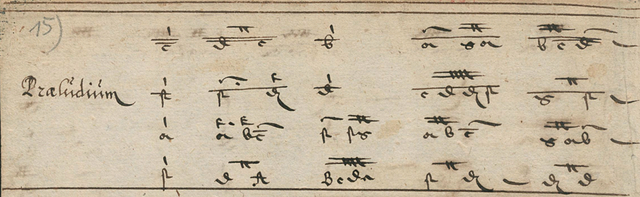

The first thing to realise is that manuscripts written in organ tablature most often use the left and right page for one system or line of music. Where in our modern notation we first play the left page and then continue on the right page, in these old manuscripts you play from the first system of the left page, to the first system on the right page, then the second system on the left page, to the second system on the right page, etcetera, etcetera. In the example above, we actually see two halves of two lines. For the rest of this blog I'll limit myself to the first halve of the first system. To be precise, this one:

German organ tablature is ideally suited to write multivoiced, or multipart music. In the example above four voices or parts are easily descernible. Organ music is firmly based in vocal music. The four parts in this kind of organ music are therefore called (from top to bottom) the soprano part (or voice), alto part, tenor part and bass part.

To denote music, you nead at least to be able to write pitch, duration and alteration (i.e sharps and flats in modern notation). The pitch in German organ tablature is notated by means of the note names: a, b, c, d, e, f, g and (because this system was used in Germany) h. As most people probably know, the note that in English (and in Dutch as well) is called b, is in German called h; the German b is the lowered h, or, in English, b flat. The symbol for the flat in modern notation is derived from this German letter b.

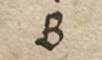

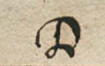

Every manuscript has slight variations in the way these letters are written, as handwriting of course differs from one person to the next. In this manuscript the a, b, c, d, e, f, g and h are consecutively written as:

and

and

The note name alone is of course not enough. On the organ keyboard (manual) there are 5 or 6 different c's, one in each different octave.

So, what c is meant when the manuscript notates  ?

?

It is probably not a coincidence that when this small letter c is written, the c from the small octave is meant (C3). I am inclined to think that the way of naming octaves in English (and in Dutch as well: "klein octaaf") is derived from the practise of notating keys from the keyboard in German organ tablature. The lowest octave from the organ keyboard is in Enlish called the great octave (and in Dutch "groot octaaf"). This naming convention is derived from the German organ tablature as well, where the keys from this octave are notated with capital letters:

and

and

For the higher octaves the small letters are used. The way to indicate the higher octaves is as simple as it is effective. For each octave up one line is drawn above the note name. The c with one line above it, is the c of the onelined octave (also known as C4, or the middle c of the piano keyboard). And the c with two lines above it is the c of the twolined octave. Again it is clear that the naming convention of the octaves in English is derived from the way of notating these octaves in German organ tabulature:

and

and  .

.

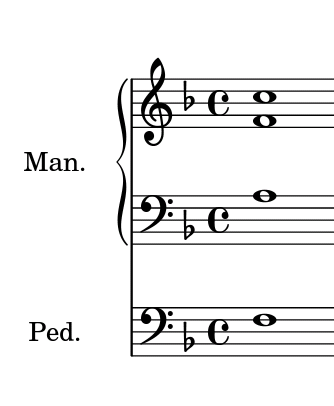

Let's look again at the first bar of the manuscript example above:

We can now see that this bar consists of the c of the twolined octave for the soprano voice, f of the onelined octave for the alto voice, a of the small octave for the tenor voice and finally the f of the small octave for the bass voice. above all these notes as "1" is written, meaning that each note has the duration of a whole note. In modern notation this first bar reads therefore:

This concludes the first part of this mini series. In the second part I'll cover more in depth the way of notating duration and the way of notating alterations in German organ tabature. Finally we can translate the entire fragment shown in modern notation.

The fragment used is part of Ms Lynar B3, owned by the Staatsbibliothek Berlin - PK. A digital copy of this manuscript can be found at: http://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN671074040

You can support me using Steem Basic Income

why did you feel the need to repost?

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I reposted it for the stemgeek community. In the original post I left out the stem tag. On second thought I considered that decision was perhaps not the right one. Hence the repost, in order to have a coherent series on stemgeek as well, since I plan to post the next part with the stem tag as well.

A repost was perhaps to much. O well, I'm only learning...

Posted using Partiko Android

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit