Go to any forum, whether it’s for producers, mixing engineers or sound designers, and you’ll always find this discussion: kicks and snares, mono or stereo? The scale tips to the mono side most of the times and I certainly agree, except when the goal is to create what I call a cinematic kick. One that is powerful, big, explosive and hits right in your ears, heart, chin and stomach.

Dissecting a kick drum

As a general rule, a kick drum has two main components. There’s the hit and there’s the rest. The hit is made of a snap (2-4 KHz) and a cardboard sound (300-600 Hz)¹. The rest is made out of low frequencies and it’s that thick punch that hits your chest like Bruce Lee.

Let’s focus on that punch for a while. Normally, if it’s rock, hip hop or electronic music, the punch is treated to be thick but always under control. Some EQ here and some compression there and we’re ready to go. That’s it? Well, I don’t think so.

Learning from films

In Hollywood films, sound effects are exaggerated. They are so over-processed that sometimes they are even comical. Explosions that explode like atomic bombs, car crashes that sound like train crashes… Drop a needle in a crowded street and you’ll hear it with all the details. You could even tell where it is without watching the screen.

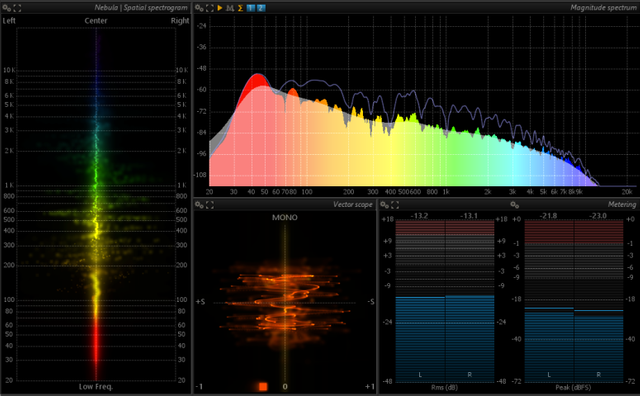

Take any powerful sound effect, be it an explosion, a car crash or two robots fighting each other; and although the low-end of these sounds goes directly to the sub-woofer, none of the details and textures are in mono.

So here’s the first thing we can learn from films: stereo is powerful. After filtering the low-end to be mono, the rest can definitely be in stereo. It adds a sense of space and makes the sound seem bigger.

And here’s the second thing: texture is important. Think of a voice’s timbre, it’s unique to each individual. That’s what texture is, it’s the timbre of any sound.

Can we combine these two concepts? Yes, we can.

Adding texture to a kick drum

Layering kick drums is a pretty common practice among music producers, in which they merge several samples into one, taking hand-picked elements from each sample. I personally like to use field recordings for adding texture.

If you’re passionate about sound, you’ve been in a situation when you hear a very interesting sound coming from somewhere and you’ve got this I-have-to-record-this! feeling. Hopefully, you had your portable field recorder with you.

That’s how you find interesting sounds, by going out and listening. For cinematic kick drums, it works better if the source sound is big and with lots of reverberation. It can be the demolition of a building, a truck’s back door being closed or the sound that the window frame makes in a train when another train is passing by very fast in the opposite direction. The more powerful and big it sounds, the better.

Recording the texture

It’s important that you have a stereo recorder with two or three built-in microphones, otherwise the surrounding richness of the sound won’t be captured. Then, place yourself in the center of action. Imagine that you are in a movie and everything happens around you. That’s what the sound should sound like. Try different positions and always record more than you need.

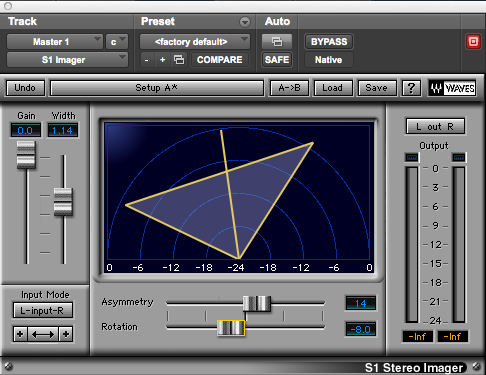

Image: Waves S1 Stereo Imager

Layering the kick

I wrote an article about layering some weeks ago. I also wrote another one in which I explain why you should keep the bass in the center. That’s the starting point, so after selecting the part you want to use (i.e. edit, cut & paste), split the sample in two layers, one mono layer for the low-end and one stereo layer for the rest (again, this is explained here).

We start with the bass: the low-end might need some compression to keep it under control. Remember that it will merge in with your other sample’s low-end, so treat them as a whole. If the low-end of one sample is not necessary, don’t be afraid to take it away. Sometimes, less is more. When the bass of the kick is ready, we can move on.

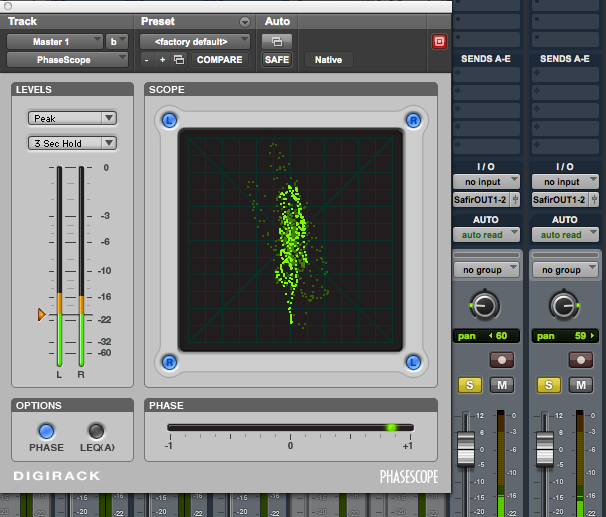

The rest: Now that the low-end is treated, the fun starts. So far, there are two untreated layers, one comes from the actual kick, and the other one comes from your field recording. Ideally, the field recording is properly centered and the sound doesn’t bend to one side. If that happens, there are some plugins that can help you fixing it. Waves’ S1 Stereo Imager is a good one. Once you have it centered, you need to verify the phase. If there are phase issues, you can easily fix that by narrowing the stereo field. For instance, from -100 | +100 to -60 | + 60.

Image: Fixing phase issues by narrowing the stereo field

At this point, you can start polishing the sound by adding some distortion or any other effect. Remember that all the layers must work as a whole, so it’s a good advice to adjust the field recording while listening to the kick sample at the same time. As for the kick sample, just keep it in the center (in mono).

When you are happy with the result, merge these two layers with the other two (the low-end previously treated). Adjust the volumes and some other minor things and voilà, a cinematic kick drum. If everything worked well, it should kick firmly and it should sound big and wide².

Remember that you are not making a film, so it’s a good idea to use this cinematic kick wisely. If you use it during the whole track, it may be too much. On the other hand, when used on specific parts, it can add an energetic punch to make the crowd bounce and head-bang to it.

(1: source: http://www.audio-issues.com/music-mixing/drum-eq-guide/)

(2: example, at 0:16: https://soundcloud.com/miguelangelux/reincarnare)

Written by Miguel Chambergo

This article was originally published in CrackingSound

Follow us on Facebook: Cracking Sound

I love your page mate! Super informative, I will be eating up your posts like food, I am a producer myself with very little technical know-how and barely any music-theory knowledge, but I can play music and create it, just on the theoretical side I am way behind!

You are a treasure trove! Thanks for taking the time to write up these tips and tutorials! Great content!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit