Noise can be so beautiful. It can be mellow and relaxing. If you have the chance to go sailing, you’ll hear that the ocean produces several sounds at the same time when you are in the open sea. The waves crashing, the tide swinging, the water being cut by the boat… There is also another sound, lower and subtle, that you’ll hear if you actually listen. It’s there, hidden in the background, unifying all the other sounds, wrapping them up with high and sublime frequencies. It’s very similar to white noise and it’s very relaxing. It’s one of my favorite sounds in nature and reason enough to spend the day sailing, despite the later one-week-long sunburn I need to pay as a price.

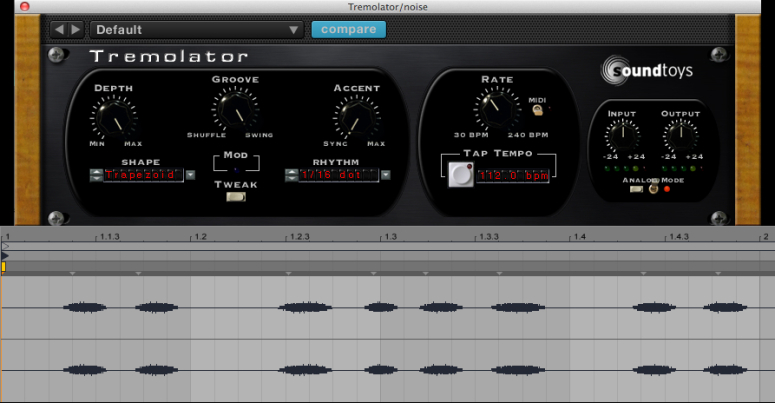

Image: White noise being modulated with Tremolator, using a trapezoid signal synchronized to dotted 16th notes.

In music, noise normally means craziness. It’s synonym of distorted guitars and screams; it equals deep emotions and tormented past memories; it unveils the animal within every one of us. It doesn’t have to be that way all the time, though. It could also evoke such quiet moments like a sailing journey in open seas or create rhythmic patterns we can dance to.

The magic trick

The magic starts when a sustained noise (any noise, not only white noise) is interrupted in musical intervals. Imagine a simple silence being introduced at every quarter note on a regular 4/4 rhythm. I guarantee you that it sounds a lot better than a metronome. For better results, try it on eighths.

An easy way to do it is to use a tremolo effect and synchronize it to the song’s tempo. The tremolo effect modulates the amplitude of the signal, which means that the volume of the noise will fluctuate at steady intervals, defining the rhythm we get as a result. For a quick idea of what it could sound like, imagine replacing a snare drum with a hit of noise.

Shaping the rhythm

For escaping the boredom of a simple quarter-note pattern, the first step is to try different modulating signals. Square or pulse signals create a straightforward, binary rhythm. Their fixed-length wave pulses don’t provide any groove by themselves, but that can still be achieved if combined with some other percussion elements. For more danceable rhythms, though, I prefer to use signals with a variable pulse length, such as the trapezoid. On the other hand, ramp signals can add a rhythmic cadence that perfectly matches down-tempo tunes.

Playing with the dry/wet ratio can also make the difference. We can say that the wet signal is responsible for the rhythm but the combination of both, dry and wet, is responsible for the groove. Think of a jazz drummer who plays the hi-hat at different volumes at a very fast speed. The dry/wet combination accentuates certain beats over others and that creates a very likeable effect.

Image: Comparison of two different modulating signals. Left: square signal tremolo. Right: ramp-up tremolo. Note: the signals are not in phase.

The power of triplets and dotted notes

Standard quarter and eighth notes are fine but triplets are better. Triplets create this kind of Latin-blooded rhythm every one wants to dance to. I am not a music theory expert so I can not really tell the reason behind. All I can say is that triplets are catchy. Dotted notes are worth trying as well. Honestly, try them. You won’t regret it at all.

Gimme some groove

So far, we have covered all the basic technical aspects:

-Selecting the right rhythm (quarter notes, eighth notes; triplets, dotted notes, etc.)

-Selecting the modulating signal (ramp, square, triangle, etc.)

-Selecting the dry/wet ratio (25%, 50%, 100% wet, etc.)

That doesn’t mean that you have to stick to them from beginning to end. Actually, some nice and complex rhythmic patterns can be obtained if any of those elements changes within the same bar. If a bar has four beats, using eighth notes on the first two beats and changing to sixteenths on the last two creates an appealing rhythm.

Layering comes very handy as well. By creating two different layers of the same noise, different modulating signals can be applied simultaneously (for instance, a ramp-up and a square), thus creating a complex rhythm. And don’t forget that you can apply a different equalization to each layer. The possibilities are only limited by your own creativity.

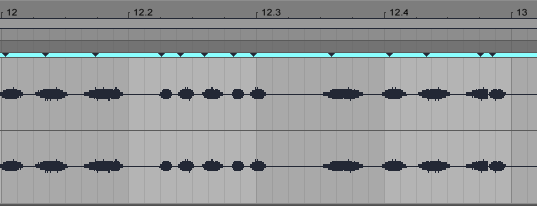

Image: White noise modulated with a trapezoid signal. The synchronization changed from dotted 16ths to dotted 32ths.

Modulating noise with an external signal

An external sound or instrument can be used as a modulator as well. The advantage of using a rhythmic guitar, for instance, is that the result is more "human", since no matter how good a guitar player you are, your rhythm will never be as perfect as that of an oscillator. And that's a good thing.

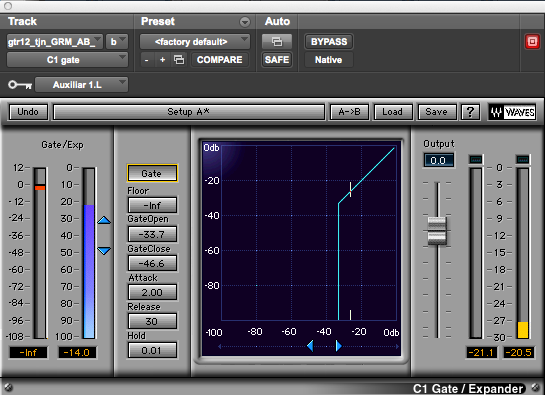

For using an external sound to modulate the noise, you need a gate with a side-chain input, where the external sound acts as a "stimulator" (side-chain). Whenever the external sound reaches a certain -adjustable- threshold, the gate opens. Thus, the noise is allowed to "pass by". That means that there's a silence when the external sound is down and there's noise when it's up.

The disadvantage of this method is that the gate doesn't give too many options for modulation as a tremolo does. In addition to the threshold, the only parameters we can control are the attack and release; i.e. how fast the gate opens and how much time it remains open before being released.

Image: A gate with side-chain input. The gate opens when the side-chain signal level is above the threshold (vertical blue line).

Sailing with the noise

As a final note, I'd like to add another idea for creating rhythms with noise. Back to the sailing story, the white-noise kind of sound that I mentioned is a fixed, sustained sound. It's like a drone note that sounds eternally, but because of its richness and subtle changes, it doesn't bother.

When creating rhythms out of noise, sometimes I like to keep a sustained and untreated noise for a while, like half a bar, and combine it with the rhythmic patterns created with the tremolo. That combination creates a nice groove, introducing a peaceful pause in which the rhythm sort of rests before continuing its dancing journey, the same way the tide does in the open sea.

Written by Miguel Chambergo

This article was originally published in CrackingSound

Follow us on Facebook: Cracking Sound

Thank you! Promoted.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you, I appreciate it. :D

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit