There are a number of outstanding issues involving Richard Wagner’s bass trumpet which are not dealt with in the literature and which I have been at a loss to resolve through my own research:

What precisely was the instrument Wagner had in mind when he began the composition of Der Ring des Nibelungen?

Why is the bass trumpet in the Ring written as a transposing instrument in C, D and E-flat when, apparently, no such instrument ever existed? The instrument used in the first performances of the Ring was crooked in C, B-flat and A.

What precisely was the instrument that the Berlin firm of Carl Wilhelm Moritz constructed for Wagner and which was used at the première of the Ring cycle in 1876?

I have consulted several supposedly reputable works on orchestration, only to find that they contradict one another on a number of crucial points.

Brobdingnagian or Gargantuan?

First, let us examine the vexed question of Wagner’s original conception of the bass trumpet. The Wikipedia article on this instrument describes Wagner’s bass trumpet as a gargantuan instrument pitched in 13' E-flat (which, in Wagner’s day, was somewhat sharper than today’s E-flat), but it does not cite any source for this information other than a vague reference to similar such instruments being in contemporary use in military bands. The earliest source I have found is Cecil Forsyth’s Orchestration (1914), which describes the instrument as “Brobdingnagian”. Forsyth gives the range of the instrument as extending from the 3rd harmonic to the 19th, but he does not specifically mention 13' E-flat. In fact, he gives the chromatic compass as extending from G2 (bottom line of the bass clef) to G5-flat (top of the treble clef). A 13' E-flat tuba can go more than an octave lower than this—but it can play the 1st and 2nd harmonics. If a 13' E-flat tuba were restricted to a compass that went no lower than its 3rd harmonic, it could, with the help of three valves, reach E2, three semitones lower than Forsyth’s lowest note. (See the note on Pitch Notation at the end of this article for an explanation of terms like 13' or G2.)

In The Wagner Compendium: A Guide to Wagner’s Life and Music, Jonathan Burton says that the instrument Wagner originally envisaged was pitched an octave below “the long E-flat trumpet”, but he too fails to cite a source. I would like to know where this idea of a bass trumpet in 13' E-flat originated. As the instrument was never actually constructed, how do we know what Wagner imagined? Did he communicate his ideas to someone else? Did he commit them to paper?

It is interesting to find that as early as 1884 Oskar Franz was speculating that Wagner’s original concept was for a smaller instrument pitched in 7' E-flat, an octave higher than Forsyth’s Brobdingnagian trumpet. But this would hardly be a bass trumpet. In fact, valve trumpets in E-flat of this length were used throughout the 19th century, being the standard size of valve trumpet in military bands. Is there any evidence that this was the instrument Wagner had in mind when he began the Ring?

The Saxotromba

In November 1853, when Wagner began the composition of Das Rheingold, he drew up a list of the instruments that he intended to use in the work. This was written on one side of a sheet of paper, with an early draft of the opera’s opening scene on the other side. This list, which is quoted by Bailey in The Wagner Companion, includes the following items:

- 8 Hörner (4 Saxhörner—bass (B), baryton (B), tenor (Es), alt (B))

- 3 Tromp.

- 1 Saxtromp (à 4 cyl.) in Es

In October of this year Wagner had paid a visit to the Belgian instrument-maker Adolphe Sax’s workshop on Rue St Georges in Paris, and examined several new instruments that Sax had patented in 1845. Among these were the saxhorns and the saxotrombas. Wagner must have felt that the saxhorns would make suitable adjuncts to the large complement of horns he intended to use in the Ring, as their appearance in the list of instruments in parenthesis after the “8 Hörner” clearly indicates that he expected four of his horn players to double on them. It is even possible that he heard the Distin family, “who were still touring Europe at that time, having recreated their quintet using early Sax bell-forward saxhorns as far back as 1844” (Carse, quoted in Webb).

As for the Saxtromp, this is clearly a reference to another of Sax’s recent inventions, the saxotromba, which, as its name indicates, was a type of trumpet. It seems obvious then that when Wagner began the composition of the Ring, his plan was to use a saxotromba as the bass member of his trumpet group. So much for Wikipedia’s “instruments he would have come across during his dealings with military bands.” Nevertheless, there may be some truth in that statement. Some years later, in a letter to Josef Standhardtner in Vienna dated 16 October 1862, Wagner did remark in relation to bass trumpets:

At the time I had chosen these instruments from the catalogue of instruments of Sax in Paris, where they were to be found in all the military music. (Heise 7)

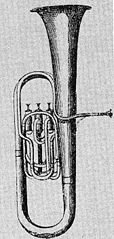

But what type of instrument was the saxotromba? According to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, the saxotrombas constituted a family of brasswind instruments designed specifically for mounted military bands and patented by Sax in 1845. Their bore profile “was probably intermediate between the ‘cylindrical’ bore of [contemporary] valved trumpets and trombones and the more conical bore of the smaller saxhorns,” but as no instruments have survived which can be positively identified as saxotrombas, this cannot be confirmed. Unlike the saxhorns, the saxotrombas never caught on and were obsolete by about 1867, nine years before the première of the Ring.

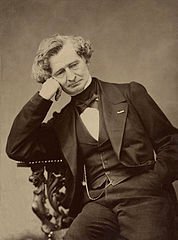

In an article in the Musical Times and Singing Class Circular entitled “New Instruments” (1 October 1860), Hector Berlioz describes several of Adolphe Sax’s new inventions, including the saxotrombas:

These are brass instruments with mouth-piece, and with three, four, or five cylinders, like the preceding [ie the saxhorns]. Their tube being more contracted, gives to the sound which it produces, a character more shrill,—partaking at once of the quality of tone of the trumpet and that of the bugle.

The number of the members of the family of saxotrombas equals that of sax-horns [ie nine by Berlioz’s reckoning]. They are disposed in the same order, from high to low; and possess the same compass.

This is repeated almost verbatim in Berlioz’s celebrated Treatise on Orchestration, though a recent translator Hugh Macdonald doubts that Sax ever produced as many models as Berlioz claims. Horwood’s biography Adolphe Sax includes a photograph of four different sizes of saxotromba. Some of this is contradicted by the article on saxotrombas in Grove, which tells us that these instruments were “pitched in B-flat and E-flat, with an additional member in F,” and that they were designed “to replace french horns in military bands.”

Berlioz describes three saxhorns in E-flat: a soprano, a tenor and a double-bass. Of these the tenor would seem to have the right range for Wagner’s bass trumpet part (in Das Rheingold, at least), sounding chromatically from A2 (bottom space of the bass clef) to G5 (top of the treble clef).

Thus Wagner’s “Saxtromp ... in Es” (“saxotromba in E-flat”) would have been pitched in 7' E-flat, a major second lower than the standard valve trumpet in 6' F. The harmonic series of a saxotromba in 7' E-flat would have had a fundamental sounding E2-flat, one ledger line below the bass clef. Was this available? Probably not, although we cannot discount the possibility that the instrument’s unique bore made it a whole-tube instrument (ie one in which the fundamental is playable). It is much more likely that it was a half-tube instrument like the tenor saxhorns (and, of course, the regular trumpet), which shared the same compass according to Berlioz. The saxotromba’s 10th harmonic would have sounded G5 (at the top of the treble clef), which Berlioz indicates was the topmost note.

Sax built his brass instruments with the Berliner Pumpventil, or Berlin pump valve, patented in 1835 by Wilhelm Wieprecht. This type of valve used a short, very thick piston. According to Wagner the Saxtromp had four valves (“à 4 cyl.”), and this agrees with Berlioz’s description. In the early nineteenth century, when four valves were applied to half-tube instruments they normally lowered the pitch of an open harmonic by 1, 2, 3 and 4 semitones respectively (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition, “Valves”). Berlioz, however, notes that in the case of “an instrument with four cylinders, the chromatic compas[s] of the low part of this instrument no longer stops at [written] F# [a tritone below the second harmonic] but goes down to the first C [ie the written fundamental].” He notes, however, that the “first low note of the tube’s resonance ... is too bad to be employed.” This implies that the fourth valve of the saxotromba lowered the pitch of a given harmonic by 5 semitones.

In the former case the valves, used independently, could have bridged the gap between the third and fourth harmonics. In either case, to bridge the gap between the third and second harmonics the valves would have to be used in combination. This led to inaccurate intonation, which could only be partly rectified by the player’s technique. Nevertheless, the use of “independent” valves in combination is well documented from this era. (By 1858 “compensatory” valves were being used to obviate the intonational problems which arose when valves were used in combination.) Thus the saxotromba in 7' E-flat had a complete chromatic scale from the second harmonic, with as many as ten or eleven “pedal tones” below the second harmonic.

Sax did make instruments with six independent valves, which were able to bridge the gap between the second and third harmonics. Does the fact that the saxotromba in E-flat had only four valves mean that its second harmonic was not playable? Or does it mean that its valves were not independent valves after all? The Berlioz article seems to indicate that the valves were meant to be used in combination.

What about the top end of its range? The compass of both the horn in 12' F and the valve trumpet in 6' F reached the 12th harmonic in the nineteenth century. Saxhorns, according to Forsyth, only went as high as the 8th harmonic, but according to Berlioz, the tenor saxhorn went up to the 10th harmonic! The tenor trombone could certainly reach the 10th harmonic. If the bore of the saxotromba was intermediate between the cylindrical bore of the trumpet and the conical bore of the half-tube saxhorns, it seems reasonable to assume—there’s that nasty word again!—that the saxotromba could reach the 10th harmonic. This, as I have said, would seem to be confirmed by Berlioz’s article.

If we make the initial assumptions, then, that Sax’s saxotromba in E-flat was fitted with four independent valves of one, two, three and five semitones respectively, and that it could sound all the harmonics from the 2nd through 10th, then the chromatic range of this instrument would have sounded from E2 (one ledger line below the bass clef) up to G5 (top of the treble clef). The bottom note in this range would require all four valves to be used in combination—a practice not recommended for independent valves, due to the difficulties of intonation. This compass, as it happens, covers the entire range of the part Wagner wrote for the bass trumpet in the Ring, which extends from G2-flat at the bottom of the bass clef to G5-flat at the top of the treble clef!

Whatever the truth, one thing is clear: the part Wagner wrote for the bass trumpet in the Ring could not possibly have been written with a 13' instrument in mind. Forsyth notes that the uppermost note required by Wagner would have been the 19th harmonic on such an instrument. Even during the Baroque era, when virtuosic trumpet-playing in the clarino register was cultivated, performers only rarely went as high as the 19th harmonic! Wagner could not possibly have believed that such an instrument would be practicable, so I am inclined to believe that Forsyth’s 13' bass trumpet was as chimerical as Jonathan Swift’s Brobdingnagians.

But what about Das Rheingold, which only takes the bass trumpet as far north as C5, the 8th harmonic (lowered 3 semitones) of a 13' instrument!

Das Rheingold

By the time Wagner began to orchestrate Das Rheingold (February 1854), he had come to the decision that instead of employing actual saxhorns in his horn department, he would instead have special hybrid instruments constructed for the purpose. These, of course, were eventually designed to his specifications and became the so-called “Wagner Tubas”. He was probably inspired to do this by the realization that four horn players would not be able to double on saxhorns, which are quite different instruments. The saxhorns have cup-shaped mouthpieces, while those on the horns are funnel-shaped. The saxhorns have four piston valves, while the horns have three rotary valves. Finally, the two deeper saxhorns Wagner originally intended using are whole-tube instruments, whereas the horn in F is a half-tube instrument. Financial considerations—the necessity of hiring four extra players to play the saxhorns—probably led Wagner to conceive of the Wagner tuba, a horn-saxhorn hybrid that sounded like the saxhorn but could be played by a horn player.

I believe—and here I am speculating again—that he also decided at this point that in place of Sax’s saxotromba he would instead have a true bass trumpet constructed, but one which had the same range as the saxotromba in E-flat. In other words, the bass trumpet he had in mind when he started scoring Das Rheingold was to be a four-valved trumpet pitched in 7' E-flat. A glance through the score of Das Rheingold will show that the bass trumpet is notated throughout as a transposing instrument in E-flat, sounding a major sixth lower than written. What’s more, Wagner was quite conservative in his use of the instrument, particularly where the lower part of its compass was concerned. The highest note he wrote—sounding G5-flat at the top of the treble clef—was the 10th harmonic (lowered by one semitone). The lowest note—sounding C3, one octave below middle C—was the 2nd harmonic (lowered by 3 semitones), or even the 3rd harmonic (lowered by 10 semitones). As it happens, the high G5-flat was the furthest north Wagner ever took the instrument, whereas the low C3 was a full tritone higher than the lowest note he was to demand in the other Ring operas (G2-flat). This fact alone surely gives the lie to Forsyth’s “Brobdingnagian” theory. Whatever may have been Wagner’s initial thoughts on the matter, he certainly never wrote for any such monstrosity.

Wagner’s Valve Trumpets

Perhaps a few words should be said here about the three other members of Wagner’s trumpet group. These were standard 19th-century valve trumpets in 6' F. They were notated almost exclusively in the treble clef, but they were not always written as transposing instruments in F, sounding a perfect fourth higher than written. Wagner often engaged in what might be called expedient false notation, writing for his F trumpets as though they were crooked in C, D, E, or E-flat (a practice for which he is roundly condemned by Forsyth). This did not mean that the players switched crooks (the nineteenth-century valve trumpet in F had no replacement crooks, being permanently crooked in 6' F), or that they used other instruments. Wagner simply chose a transposition that would allow him to write the part with as few accidentals as possible and which he believed the conductor would find easiest to read. The individual parts, I presume, could be printed throughout as transposing instruments in F, sounding always a perfect fourth higher than written. Thus when the trumpets make their first appearance in the Prelude to Das Rheingold, they are described as Tromp. (Es) (Trumpets (E-flat)), which is appropriate, as the prevailing tonality is E-flat. But at the end of the opera, where the prevailing tonality is D-flat, the trumpets are notated in F. The bass trumpet, however, is always written in E-flat in Das Rheingold, irrespective of the transposition used for the three ordinary trumpets.

Whatever the truth, the saxotromba could probably sound its second harmonic, and possibly reach all the way down to its fundamental. Furthermore, the F trumpet had only three valves, allowing the player to lower the lowest playable harmonic by a diminished fifth, whereas the four-valve bass trumpet which I believe Wagner was writing for could lower its lowest harmonic by as much as a major seventh. Thus Wagner’s putative bass trumpet in E-flat could reach more than an octave lower than the standard F trumpet.

Die Walküre

So much for Das Rheingold. When we come to Die Walküre, however, we find that Wagner has changed his mind for at least the second time, for here the bass trumpet is notated in two different keys: E-flat and D. So what is going on? Is this just another example of expedient false notation? Apparently not. If it were, we would expect to find the bass trumpet being notated in the same keys as the other trumpets; but whereas the latter are frequently notated in C, D, E, E-flat and F, the bass trumpet is only notated in D and E-flat. Even at the end of the opera—where the tonality is pure unadulterated E-major—the first three trumpets are not unsurprisingly notated in E, whereas the bass trumpet is in D.

So it would seem that Wagner really does have a new instrument in mind, one in which his Rheingold bass trumpet in E-flat can now be fitted with a replacement D crook, converting it into a bass trumpet in 7½' D. I can only speculate as to his reasons for making this change. Perhaps he feared that the lowest notes would be difficult to play with the E-flat crook.

It is of course possible that Wagner intended the bass trumpeter to have two instruments, one in E-flat and one in D, but if this were the case the list of instruments at the beginning of the score would surely have made this clear. The clarinets, for instance, are listed as tuned in A and B-flat, implying that each clarinettist should be equipped with two different instruments. The bass trumpet, on the other hand, is listed as simply, 1 Basstrompete. (Btr.).

Siegfried

Whatever the reason, this was not the last time Wagner was to have a change of heart as far as the bass trumpet was concerned. When we open the score of the next opera in the cycle, Siegfried, we find the bass trumpet now being notated in three different keys: C, D and E-flat. Actually, the change from a bass trumpet in D and E-flat to one in C, D and E-flat only occurs in Act III, which Wagner composed more than seven years after he had completed the first two acts. It would seem that these new ideas on the bass trumpet occurred to him during this lengthy hiatus.

But why the change? Perhaps Wagner now felt that an instrument designed for trumpeters should have three valves like other valve trumpets. Without the fourth valve, the only way of reaching the low G2-flat would be by pitching the instrument in C and using compensatory valves (which came into use in 1858, just after Wagner had completed Acts I and II of Siegfried). But then the top G5-flat would require the player to play the 12th harmonic, whereas in Das Rheingold the top note could be played as E-flat’s 10th harmonic. The use of crooks in combination with valves would solve both problems. The C crook could be used for the lowermost notes and the E-flat crook for the uppermost. Of course the D crook would now be redundant. Perhaps Wagner retained it as it made the part easier to read in certain keys.

Wagner then continued with the composition of the Ring, confident that when the time came for the work to be performed, it would be quite easy to have the required instrument constructed. Consequently, he notated the bass trumpet in the full scores of Siegfried and Götterdämmerung as a transposing instrument crooked in C, D and E-flat, sounding respectively an octave, a minor seventh and a major sixth lower than written in the treble clef. At a few places in the scores of Die Walküre and Siegfried he notated the bass trumpet in the bass clef, in which cases it sounded higher than written. As we have seen, the range he required in these three operas was somewhat larger than that of Das Rheingold, extending as far south as G2-flat at the bottom of the bass clef.

Götterdämmerung

Wagner’s scoring of the bass trumpet in the final Ring opera, Götterdämmerung, casts serious doubt, however, on the theory that the bass trumpet in C, D and E-flat was a crooked instrument. In Act II Scene 3 (p. 704, mm. 1-2, of Eulenberg Miniature Score No. 910, at the moment Gunther and Brünnhilde arrive on the banks of the Rhine) he notates the instrument in C and E-flat in quick succession, leaving just two quarter-tone rests—the tempo is Sehr lebhaft, or vivacissimo—for the change. This is much too short an interval of time for a change of crook (or even a change of instrument). Perhaps the changes of notation employed in the last three Ring operas are after all simply instances of expedient false notation. But why, then, did Wagner not notate the bass trumpet like a regular trumpet, and trust that when the time came to perform the Ring, the individual parts would be printed in a transposition that best suited the player? Perhaps he anticipated that his bass trumpet would be played by a trombonist (as it often is), and he wanted to keep the transpositions as simple as possible.

Another possibility is that Wagner envisaged a bass trumpet with a thumb-operated trigger valve that would lengthen the instrument’s tube. This would have the same effect as a change of crook, but it could be engaged and disengaged almost instantaneously. Such a device is commonly used on modern double horns, allowing the instrument to be played in F or B-flat. Similarly, many tenor trombones are fitted with an F attachment, which the player engages by flicking a rotary valve with his thumb. However, I do not think such a device would explain Wagner’s instantaneous changes of crook. For starters, Wagner’s bass trumpet would require two such triggers, making the instrument a triple trumpet, which is highly unlikely. And secondly, there is no mention of any such trigger in the literature.

The C W Moritz Instrument

When Wagner finally discussed his ideas for a bass trumpet with the firm of C W Moritz, the latter (then managed by the founder’s son Johann Carl Albert Moritz) seems to have convinced him that the instrument he envisaged—even in its revised form—would be impractical. Perhaps Moritz feared that if the instrument was to be truly trumpet-like in its timbre, it would need to be constructed with a bore and mouthpiece that would not facilitate the playing of the 2nd harmonic. He may then have suggested that a more practical solution would be to construct a three-valve instrument of such a pitch and bore that all the harmonics could be obtained from the 2nd through the 12th (rather than the 2nd through the 10th). Then the lowest note Wagner required could be played from the 2nd harmonic of a low 9½' A crook (sounding A2, at the bottom of the bass clef). Three valves, used independently, could lower this by as much as three semitones to G2-flat, the lowest note Wagner required.

The instrument Moritz eventually constructed for Wagner in 1866 was pitched, it is said (New Grove), in 8' C with two additional crooks in B-flat and A. This is supported by the German periodical Zeitschrift für Instrumuntenbau (1907-08, S 635). Speaking of J C A Moritz’s contributions to the firm, Wilhelm Altenberg writes:

His inventions and improvements were extremely comprehensive and versatile. To mention only the most important, he constructed at Richard Wagner’s personal suggestion, and for the performance of Wagner’s Music dramas [Das Rheingold and Die Walküre] at the Royal Theatre in Munich [in 1869 and 1870], the bass trumpet in C, B-flat or A, with three valves...

The 2nd harmonic must have been playable, then, as well as the 12th. Furthermore, if the three valves were used in combination, then the entire range of Wagner’s bass trumpet part could be played on the C crook without any need for a fourth valve, or the other crooks , or transposing parts. As a consequence, instrument makers began to make the instrument in 8' C with only three compensatory valves and without any crooks. According to Forsyth, Piston and Del Mar, such a bass trumpet in C is now used for all the bass trumpet music in the Ring, irrespective of which crook Wagner actually calls for in the scores, or which key he notates the instrument in.

To my knowledge, no specimens of the Moritz instrument have survived, so we know as little about it as we do about Sax’s saxotromba. But Wagner himself does reveal a morsel of information in a letter to the Dresden trumpeter Benjamin Friedrich Queisser. Queisser was Wagner’s choice as first trumpet for the première of the Ring at Bayreuth in 1876:

Or do you want to play the bass trumpet ... (an 8' deep instrument, and so in the tenor register) which I had specially designed, and which I could soon send you to practise on? It would mean a lot to me to know that this primarily melodic [melodie-führende] instrument was in good hands. (Heise 7)

No mention of crooks, but we do have confirmation that the instrument was in 8' C (two octaves below Middle C).

Of course, by the time all this had taken place, Wagner had already completed the Ring with the bass trumpet part notated in C, D and E-flat, and he was probably not prepared to go to the trouble of reissuing the scores to accommodate Moritz’s new instrument. Perhaps he reasoned that the individual parts could be printed in whatever transpositions suited the players, while anyone consulting the full score need only know how to transpose music in order to be able to follow the part. This theory has the advantage of explaining why the bass trumpet in the full scores of the Ring operas was written in C, D and E-flat while the instrument on which it was actually played was pitched in C, B-flat and A.

If this line of reasoning is correct—and I emphasize that most of what I have written here is speculation—then it follows that the bass trumpet part in the full score of the Ring was written for a notional instrument (or possibly two, three or four notional instruments) that never had any real existence outside of Wagner’s imagination. That surely calls for some comment in the literature—a footnote at the very least, if not an entire paragraph. Yet there is no mention of any such thing in the sources I have consulted.

Literature

So much for the music. Now let’s take a quick look at the literature.

Jonathan Burton, “Orchestration” in The Wagner Compendium: A Guide to Wagner’s Life and Music

Burton says that Wagner’s initial plan was for an instrument pitched an octave below the “long E-flat trumpet”, but that “Wagner settled for a smaller but still majestic instrument crooked in C, D or E-flat, built for him by Moritz.” This seems to be a mishmash of half-truths, at best.

Walter Piston, Orchestration

Piston speaks of Wagner writing for a bass trumpet “in the [key] of 8-foot C”. There is no mention of any crooks or notation. I think we can safely say that before the third act of Siegfried, Wagner did not write for any bass trumpet in C.

Samuel Adler, The Study of Orchestration

Adler merely mentions bass trumpets in C, B-flat and E-flat, gives the range and notation of each, and then quotes two pieces from Die Walküre for “B. Tr. in D”.

Norman Del Mar, Anatomy of the Orchestra

Del Mar says that “despite the many crooks in which it is written, the bass trumpet in C is the one most commonly used by the players.” As regards the range, however, he says that “Wagner wrote no lower than F [F3, written three ledger lines below the treble clef],” while “At the upper end ... limiting it to A [A5, written one ledger line above the treble clef].” These limits, whether they are to be read as written or sounding notes, simply do not accord with the facts. Furthermore, he says that Wagner always used the treble clef for his bass trumpet, but this is only true of Das Rheingold and Götterdämmerung. There are a number of places in the two other Ring operas where the bass trumpet is notated in the bass clef, sounding higher than written.

Cecil Forsyth, Orchestration

The actual instrument used in the Ring was “the instrument which we now possess ... The player is asked to produce no Harmonic lower than the 2nd or higher than the 10th: C4 [written as Middle C, sounding an octave lower] to E6 [written three ledger lines above the treble clef]. For orchestral use the instrument is built in the key of C-basso only. It has no need of additional crooks. By means of its three valves it has a complete chromatic compass downwards through a diminished fifth to F# and upwards to its highest note E ... sounding: F2# [at the bottom of the bass clef] to E5 [at the top of the treble clef].” Wagner, however, requires his bass trumpet to go a whole-tone higher than this.

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

According to the New Grove, Wagner originally conceived a bass trumpet pitched an octave below the trumpet in 6' F. This is yet another variant of Forsyth’s Brobdingnagian theory. Grove, however, does agree with Wikipedia that Moritz’s eventual instrument was an 8' C trumpet with crooks in B-flat and A.

Pitch Notation

The pitches of brass instruments are sometimes given in terms of the length of open pipe on the organ that produces the same note as the brass instrument’s fundamental tone (or first harmonic), even if that fundamental cannot actually be played. Feet (and inches) are used for this purpose, even in countries that generally use the metric system. In this system C2 (two octaves below Middle C) is defined as 8-foot C. The actual length of such a pipe will vary from place to place, and from time to time, depending on the prevailing standard of pitch. Today’s concert pitch is defined as A4 = 440 Hz, so 8-foot C has a frequency of approximately 65.4064 Hz. The length of pipe required to produce this note is actually more than 8 imperial feet. If the speed of sound through air at 20° Celsius is taken to be 343 m s-1, then an organ foot—or sonic foot—turns out to be slightly longer than the imperial foot: about 328 mm, or a little more than 12.91 imperial inches. The length of a modern 8-foot pipe is actually about 8' 7.2" imperial.

E2-flat, being a minor third higher than this (~77.7817 Hz), requires an actual pipe-length of slightly more than 7' 2.8" imperial. When the Ring was premiered in 1876, however, concert pitch was about a semitone higher than it is today, so a trumpet with E2-flat as its fundamental would have had a sounding length of almost 6' 10", or about 4-5 inches shorter than today’s instruments of corresponding pitch. One octave lower, E1-flat has a modern sounding length of about 14' 5.6"; in 1876 it was almost 13' 8". In the twentieth century, tubas pitched in E1-flat were said to be in 14' E-flat (Piston 285), whereas Adolphe Sax in the middle of the nineteenth century described such instruments as being pitched in 13' E-flat;. On the other hand, tubas pitched in C1 were known in both centuries as 16-foot instruments, even though the modern ones are more than 17' long. It is, incidentally, conventional practice, when using organ-pipe pitches, to use whole numbers only: fractional parts are usually disregarded.

Throughout this discussion I refer to the various pitches using a modified form of scientific pitch notation. Middle C is defined as C4, and the notes corresponding to the eight white keys on the piano from middle C to the C one octave higher are designated C4, D4, E4, F4, G4, A4, B4 and C5. Chromatic notes are indicated by applying accidentals to neighbouring white notes. For example, the black note on the piano a tritone above middle C can be designated F4# or G4-flat. The B♮ immediately below middle C is either B3 or C4-flat.

References

- Samuel Adler, The Study of Orchestration, W W Norton & Co, New York (1989)

- Wilhelm Altenberg, “Zur Hundertjahrfeier der Musikinstrumenten-Fabrik C. W. Moritz in Berlin, Zeitschrift für Instrumentenbau, Paul de Wit, Leipzig (1907-08), S 635

- Hector Berlioz, “New Instruments”, The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular (1 October 1860)

- Peter Burbidge & Richard Sutton (editors), The Wagner Companion, Cambridge University Press (1979)

- Jonathan Burton, “Orchestration”, The Wagner Compendium: A Guide to Wagner’s Life and Music (Barry Millington, editor), Thames and Hudson, London (1992)

- Adam Carse, “Adolphe Sax and the Distin Family”, The Musical Review, VI (1945), p 193

- Norman Del Mar, Anatomy of the Orchestra, University of California Press, Berkeley (1981)

- Cecil Forsyth, Orchestration, Macmillan & Co Ltd, London (1914)

- Oskar Franz, Zeitschrift für Instrumentenbau, Paul de Wit, Leipzig (1884)

- Birgit Heise, Thierry Gelloz, Musikinstrumente für Richard Wagner: Ergänzende Anmerkungen zum Katalog „Goldene Klänge im mystischen Grund“, Museum für Musikinstrumente

- Walter Piston, Orchestration, W W Norton & Co, New York (1955, 1978)

- Stanley Sadie (editor), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Macmillan Publishers Limited, London (2001)

- John Webb, “Mahillon’s Wagner Tubas”, The Galpin Society Journal, Vol 49 (March 1996), pp 207-212

Image Credits

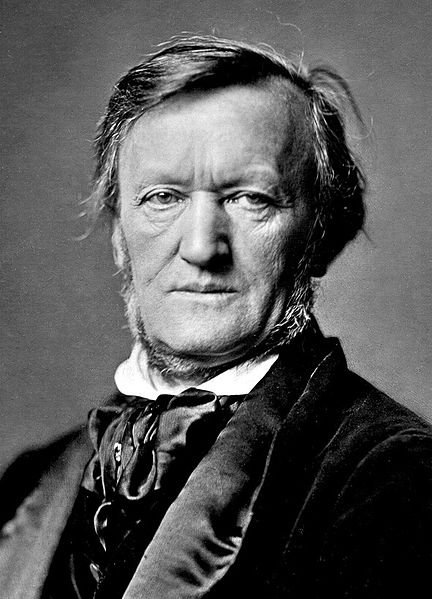

- Richard Wagner: Wikimedia, Public Domain

- Bass Trumpet: Esolomon, Creative Commons License

- Sax’s Atelier at 50 Rue Saint-Georges, Paris: Wikimedia, Public Domain

- Saxotromba: Wikimedia, Public Domain

- Hector Berlioz: Wikimedia, Public Domain

- Walter Piston: Wikimedia, Fair Use Under United States Copyright Law

- Bass Trumpeter: Esolomon, Creative Commons License

- Forsyth’s Orchestration: Paul E Kennedy, Dover Publications

Source: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:OvY2ahqTX4AJ:www.it1me.com/learn%3Fs%3DUser:Eroica/Wagner+&cd=2&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

Hello! Welcome to Steemit.

In order to prevent identity theft, identity deception of all types, and content theft we like to encourage users that have an online identity, post for a website or blog, are creators of art and celebrities of all notoriety to verify themselves. Verified users tend to receive a better reception from the community.

Any reasonable verification method is accepted. Examples include:

Thank you!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit