Sending astronauts back to the moon is one of the top space priorities of President Trump. But his administration wants to accomplish that without giving NASA additional money, and it won’t occur until after he leaves office, even if he wins re-election.

Instead, it aims to give the private sector a greater role, according to a budget proposal to be released on Monday.

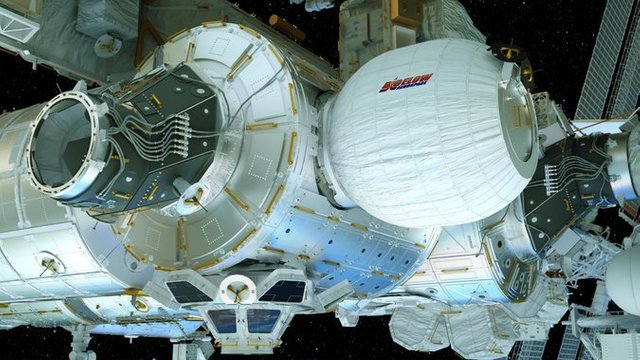

The administration is also looking to end American payments for the International Space Station by 2025. The space station is currently scheduled to operate through 2024, but the expectation was that it would be extended through at least 2028.

According to excerpts from NASA documents obtained by The New York Times before the budget’s release, the administration will propose $19.9 billion in spending for the space agency in fiscal year 2019, which begins on Oct. 1. That is a $370 million increase from the current year, the result of the budget deal reached in Congress last week and signed by Mr. Trump.

The budget numbers were confirmed by a person who was not authorized to talk publicly about them.

In future years, the administration would like NASA’s spending to drop to $19.6 billion and stay flat through 2023. With inflation, NASA’s buying power would erode, effectively a budget cut each year.

Continue reading the main story

RELATED COVERAGE

If No One Owns the Moon, Can Anyone Make Money Up There? NOV. 26, 2017

Falcon Heavy, in a Roar of Thunder, Carries SpaceX’s Ambition Into Orbit FEB. 6, 2018

The Google Lunar X Prize’s Race to the Moon Is Over. Nobody Won. JAN. 23, 2018

A NASA spokesman said he could not discuss the budget proposal until it was released.

The proposal is just an opening bid. Congress decides the final spending numbers, sometimes adjusting them or ignoring a president’s priorities. But an administration’s wishes are often incorporated.

NASA’s budget will be announced at a moment when the agency has no permanent leaders to carry out the new directions. Mr. Trump nominated Jim Bridenstine, an Oklahoma congressman, to be the next administrator, but the Senate has not yet confirmed him. Whether the administration has the votes to confirm him remains uncertain. This is by far the longest period in NASA’s history without an administrator.

Photo

Additionally, no one has been nominated for the No. 2 position, deputy administrator.

The Trump administration has also established a National Space Council, led by Vice President Mike Pence, to coordinate space policy between military and civilian agencies. The council held its first public meeting in October, and is to meet again this month.

The Trump administration is also looking to trim the budget of NASA’s earth science directorate, which includes climate research and cancel several spacecraft like the Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem mission. The nearly $1.8 billion budget for that part of NASA would be about 6.5 percent lower than what was enacted for fiscal year 2017. The Trump administration also wants to end education programs. Similar proposals last year were disregarded by Congress.

The astrophysics division would be cut by 12 percent, but overall, the budget would give an increase to NASA’s science directorate, primarily for robotic planetary missions.

Rumors of the intent to end space station financing were recently reported in The Verge and other outlets, drawing strong criticism from some lawmakers, including key Republicans.

“I hope that those reports prove as unfounded as Bigfoot,” Senator Ted Cruz, Republican of Texas and the chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Space, Science and Competitiveness, said on Wednesday during a Federal Aviation Administration conference on commercial space transportation.

He decried “numbskulls” at the Office of Management and Budget in the White House for coming up with the idea. “As a fiscal conservative, you know one of the dumbest things you can do?” he said. “Canceling programs after billions in investment when there is still serious usable life in it.”

The same conference was attended by Scott Pace, the executive secretary of Mr. Pence’s space council. While he did not discuss details of the budget, Mr. Pace suggested that money needed to be freed up for new initiatives.

Continue reading the main story

For NASA to push human spaceflight further, he said, “the kinds of commitment of resources that traditionally we’ve done in low-earth orbit, we can direct some of that toward deeper space exploration.”

The budget proposal promises “a seamless transition to the use of future commercial capabilities,” and allocates $150 million in 2019 to encourage commercial development in low-Earth orbit.

The administration proposes $900 million for this goal through 2023. If structured like earlier NASA public-private partnerships, like the ones for carrying cargo and crew to the space station, the money would be split between two or more companies.

By contrast, the United States has spent close to $100 billion building and operating the International Space Station.

The end of financing in 2025 does not necessarily mean the station would be discarded then. The Washington Post reported on Sunday that an internal NASA document asserts, “It is possible that industry could continue to operate certain elements or capabilities of the ISS as part of a future commercial platform.”

But space experts so far do not see how that would be viable economically because NASA currently spends $3 billion to $4 billion a year.

“I haven’t really seen anyone talking about that,” said Tommy Sanford, the executive director of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, a trade group representing many of the new space companies. “I think that’d be difficult.”

Mr. Sanford said the federation was concerned about setting a specific end date. He said it would be better to define benchmarks that commercial alternatives would need to achieve before the International Space Station is retired.

In recent years, more companies have started using the station in areas like pharmaceutical research and manufacturing of fiber optical cable.

“If we abruptly end that, without a smooth transition plan,” John Elbon, vice president and general manager of space exploration at Boeing, said at last week’s conference, “all that investment will be for naught.”

For a greater focus on the moon, the budget plan describes investing in commercial companies to develop and fly robotic landers to carry experiments and other payloads to the moon.

Those companies could include Moon Express and Astrobotic Technology, two companies originally created to compete for a $20 million grand prize in the Google Lunar X Prize. The X Prize Foundation conceded last month that none of the remaining competitors would be able to reach the moon before the prize expires on March 31. Both companies still plan to head to the moon in the next couple of years.

In addition, Blue Origin, a space company started by Jeff Bezos, the chief executive of Amazon, has proposed a larger lander called Blue Moon that could deliver several tons of cargo to the surface of the moon.

Efforts to increase research and development aimed at next-generation space technologies for a range of human and robotic missions, one of the priorities of the Obama administration’s space policy, would be refocused on nearer-term development on moon missions.

For astronauts, the goal is still to reach “the vicinity of the moon” in 2023. That is the current schedule for the first crewed launch of the Space Launch System, which would fly around the moon but not land.

Under the proposed timeline, work on a lander would not start until that year.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://indascience.com/news/view/22910/nasa-budget-moon.html

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit