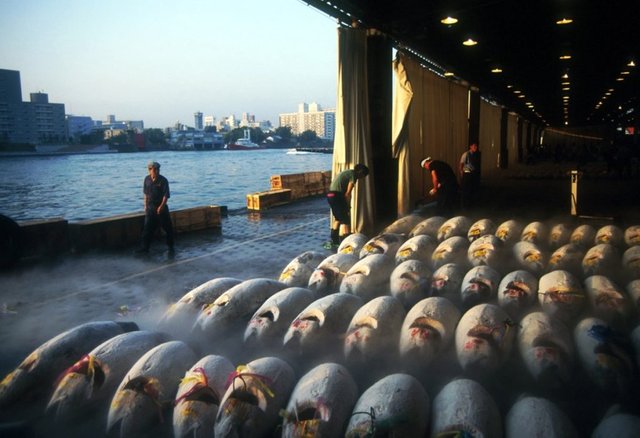

Tsukiji fish market, is known as The fish market at the center of the world by Bestor (2004) and the fishing industry’s answer to Wall Street. Ursic (2013) describes Tsukiji as an economic and cultural institution which determines the prices of specific seafood on a global level. The market at its current location was founded 1935 and is located in one of the world’s most expensive building grounds (ibid.) It is within walking distance from the upscale shopping district Ginza in central Tokyo. It is regarded as the biggest fish market in the world with more than 2,000 tonnes of seafood passing through every day (Booth, 2014).

In what ways are the Anthropocene reflected in the Tsukiji fish market?

Thedore Bestor, who has done research on Tsukiji for over 14 years, wrote an interesting article How Sushi Went Global (Bestor, 2000). The article mentions one morning in Bath, Maine, U.S, when Bestor witnessed some American fishermen with three bluefin tuna sitting in a huge tub of ice on the loading dock. Later trucks from different parts of the country arrived, and twenty tuna buyers, half of them Japanese, clamber out the trucks. After some time of eyeing the goods, and after calls to Tsukiji for the latest price updates, the buyers give written, and secret, bids to the dock manager. After three of the buyers have their bids accepted, the fish is quickly loaded onto the backs of the trucks in crates of crushed ice. The trucks loaded with fish head to New York and JFK Airport, where the tuna will be delivered by air freight to Tokyo for sale at Tsukiji. This reflects the globalization of the fish industry, and according to Swarts et al. (2010) fish is one of the most widely traded commodities in the world with nearly 40 percent of world fish production entering the international market.

Traders at Tsukiji joke that Japan’s leading fishing port is Tokyo’s Narita International Airport (Bestor, 2000). Ironically, that bluefin tuna caught in Maine might actually end up on a sushi restaurant in New York after being bought by exporters at Tsukiji, and sold back to importers in the U.S. (Bestor, 2000).

So what impact does Tsukiji fish market actually have on the Earth, and why is it relevant to the Anthropocene?

The Anthropocene could be said to have started in the latter part of the eighteenth century, when analyses of air trapped in polar ice showed the beginning of growing global concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane. This date happens to coincide with James Watt’s design of the steam engine in 1784 (Crutzen, 2002). Industrial fishing and globalization of the fish industry started when that invention was transferred to boats in the 1880s and the first steam-powered trawlers around England was deployed (Anticamara et al., 2010). The oceans cover more than 70 percent of our planet and dominate the earth in a variety of ways. With an average depth of almost 4 km, they provide over 99 percent of the habitable space for life on earth (Erlandsson & Rick, 2008).

So what happened to the earth when fishing became industrial and globalized?

As human populations have grown exponentially over the past century, and with 60 percent of the world’s population living close to the coast (ibid.), fishing have been industrialized, and demand for marine resources has grown rapidly, heavy pressure has been put on marine ecosystems. FAO (cited in: Worm & Branch, 2012) estimates that only 15% of monitored fish stocks are low or moderately exploited, and the remainder being fully exploited (53%), overexploited (28%), depleted (3%), or recovering from depletion (1%). Jackson et al. (2001) recognize three different but overlapping cultural periods of human impact on marine ecosystems: aboriginal, colonial, and global.

I contend that the Tsukiji fish market represents the period when human impact entered the global period. According to Jackson et al. (ibid.) global use involves more intense and geographically pervasive exploitation of coastal, shelf, and oceanic fisheries integrated into global patterns of resource consumption, with more frequent exhaustion and substitution of fisheries. Tsukiji fish market is globalized in many aspects, and represents the Anthropocene in several ways. One of the variables discussed by Steffen et al. (2015) concerns Genetic diversity, and mass extinction of species. Over fishing is the main threat to extinction of marine species (Nieto et al., 2015), Japan is by far the biggest consumer per capita of fish, even if a slight decline is predicted (World Bank, 2013), and Tsukiji act as a symbol for over fishing and excessive consumption of fish in Japan, and in the world.

The global trade of fish, the increase of aquaculture production (FAO, 2014), and other aspects of the fishing industry are all contributing to emissions of greenhouse gases, and by doing so it is part of our ongoing transition to the Anthropocene. Various Japanese newspapers have published numerous stories regarding over-fishing in Japan and Asia (For example, Nikkei Asian Review, 2016 and The Asahi Shimbun, 2016).

Bestor (2004) describes fish and the arts associated with its preparation and consumption as central to Japanese culinary heritage and near the emotional core of national identity. Also Anticamara et al. (2010) highlights the contribution of fishing the culture of communities in many countries. Apart from reflecting the Japanese food culture in terms of cooking and eating, Tsukiji fish market, according to Bestor (2004), also reflects food culture in terms of production and distribution of foodstuffs in social, political, historical, environmental and global contexts. Food culture at Tsukiji is shaped by the social institutions and value of capitalism as a cultural system, where the political economy of the Japanese fishing industry, the dependency on global sources of food supply, new technologies of food processing, and the complicated intersections of class and consumption are all equally reflective of our transition to the Anthropocene.

So is it cultural aspects and traditions that keep up the growing demand for seafood at Tsukiji?

Masami Yuki’s (2012) article about the Minamata disaster, where villagers knowingly ate toxic fish, strengthens to some extent such theories. Yuki concludes that the villagers close relationship to the sea produced the majority of the victims of the disaster. In Tsukiji you can find whale meat occasionally, and Ursula Heisse's (2010) article about mass extinction, examines whale hunting in Japan as a tradition which is very difficult to end. As such, culture, traditions, and heritage seem to have great influence on how Tsukiji fish market and the fishing industry in Japan are function.

But are there other causes of this, often environmentally destructive behavior, that can explain the reason why Tsukiji fish market reflects the Anthropocene?

Gowdy and Krall (2013) argue that during the transition to agriculture, some 8000 years ago, human society began to function as a superorganism - a single unit designed by socialized natural selection to produce economic surplus. This superorganism, formed when humans became ultra social – the most social form of animal organization, with full time division of labor, specialists who gather no food but are fed by others etc. – is the reason our species, in the face of impending disaster, seems incapable to make basic societal changes needed to ensure our long-run survival. As such, Heisse (2010) highlights the lack of attention given to fish in particular as well as amphibians, reptilians etc., in public discussion and debate concerning the biodiversity crisis.

References:

Anticamara, J. A., Watson, R., Gelchu, A. and Pauly, D. (2010) Global fishing effort (1950-2010): Trends, gaps, and implications, Fisheries Research, vol. 107, pp. 131-136

Asahi Shimbun, The (2016) Sushi alert: Grim outlook for world’s bluefin tuna stocks [Online), The Asahi Shimbun, April 20,

Bestor, T. C. (2000) How Sushi Went Global, Foreign Policy, vol. 121, pp. 54-63

Bestor, T. C. (2004) Tsukiji, The Fish Market at the Center of the World [e-book], University of California Press.

Booth, M. (2014) Tokyo’s Tsukiji fish market: the world’s greatest food show, Financial Times.

Crutzen, P. J. (2002) Geology of mankind, Nature, Vol. 415, p. 23

Erlandsson, J. M., & Rick, T. C. (2008) Human Impacts on Marine Ecosystems [e-book], University of California Press.

FAO (2014) The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, Opportunities and Challenges [PDF], Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, available: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3720e.pdf

Gowdy, J., and Krall, L. (2013) The ultrasocial origin of the Anthropocen, Ecological Economies, vol. 95, pp. 137-147.

Heisse, H. (2010) Lost Dogs, last Birds, and Listed Species: Cultures of Extinction, Configurations, vol. 18, no. 1-2, pp. 49-72.

Jackson, J. B. C., Kirby, M., Berher, W., Bjorndal, K., Botsford, L., Bourque, B., Bradbury, R., Cooke. R., Erlandsson, J., Estes, J., Hughes, T., Kidwell, s:, Lange, C., Lenihan, H., Pandolfi, J., Peterson, C., Stneck, R., Tegner, M, and Warner, R. (2001) Historical Overfishing and the Recent Collapse of Coastal Ecosystems, Science, vol. 293, pp. 629-637

Nikkei Asian Review (2016) Emptying seas, mounting tensions in fish-hungry Asia [Online], Nikkei Asian Review.

Steffen, W., Richardsson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S., Fetzer, I., Bennet, E., Biggs, R., Carpenter, S., de Vries, W., de Wit, C., Folke, C., Gerten, D., Heinke, J., Mace, G., Persson, L., Ramanathan, V., Reyers, B., and Sörlin, S. (2015) Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet [research article summary], Science, vol. 347, issue 6223.

Swarts, W., Sumalia, R., Watson, R., and Pauly, D. (2010) Sourcing Seafood for the three major markets: The EU, Japan and the USA, Marine Policy, vol. 34, pp. 1366-1373

Ursic, M. (2013) Preservation or degradation of local cultural assets in central Tokyo – The case of the plans to relocate the Tsukiji fish market, Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 35-60.

World Bank (2013) FISH TO 2030 – Prospects for Fisheries and Aquaculture [PDF], World Bank report no. 83177-GLB.

Worm, B. and Branch, T. (2012) The future of fish, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 27, issue 11, pp. 594-599

Yuki, M. (2012). Why Eat Toxic Food? Mercury Poisoning, Minamata, and Literary Resistance to Risks of Food. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, vol. 19, pp. 732–750.

Incredible..kawan

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Yes it is. There are many examples I have written about in relation to how our species has been historically increasing the impact of the Anthropocene.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Good content! Whale done:)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Why thank you! How appropriate is your name for my article too ;)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit