Since Europeans first arrived in the New World, there have been stories of a legendary jungle city of gold, sometimes referred to as El Dorado. Spanish Conquistador, Francisco de Orellana was the first to venture along the Rio Negro in search of this fabled city. In 1925, at the age of 58, explorer Percy Fawcett headed into the jungles of Brazil to find a mysterious lost city he called “Z”. He and his team would vanish without a trace and the story would turn out be one of the biggest news stories of his day. Despite countless rescue missions, Fawcett was never found. Was he killed by Amazonian tribesmen? And is there any factual basis for his Lost City of Z?

Since Europeans first arrived in the New World, there have been stories of a legendary jungle city of gold, sometimes referred to as El Dorado. Spanish Conquistador, Francisco de Orellana was the first to venture along the Rio Negro in search of this fabled city. In 1925, at the age of 58, explorer Percy Fawcett headed into the jungles of Brazil to find a mysterious lost city he called “Z”. He and his team would vanish without a trace and the story would turn out be one of the biggest news stories of his day. Despite countless rescue missions, Fawcett was never found. Was he killed by Amazonian tribesmen? And is there any factual basis for his Lost City of Z?

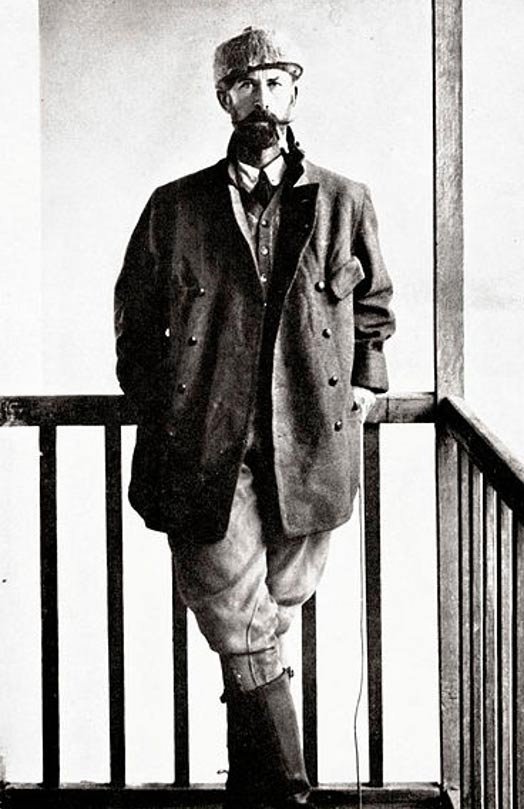

Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett was born in England in 1867 and was a famous British explorer who’s legendary adventures captivated the world. An officer in the Army and trained surveyor, Fawcett was the last of the great territorial explorers; men who ventured into blank spots on the map with little more than a machete and a compass. For years he would survive without contact in the wilderness, and befriend tribes who had never before seen a white man. His exploits in the Amazon inspired books and Hollywood movies; Indiana Jones is purportedly based on Fawcett.

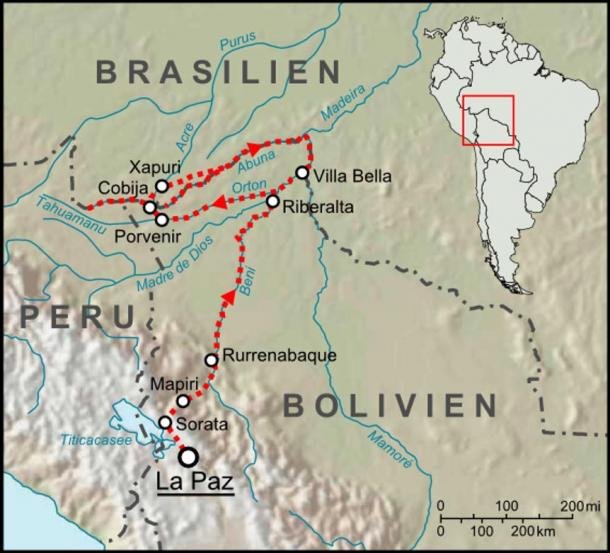

The Amazon wilderness is about the size of the continental United States and during Fawcett’s time, it remained one of the last unexplored regions on the map. In 1906, the Royal Geographical Society, a British organization that sponsors scientific expeditions, invited Fawcett to survey part of the frontier between Brazil and Bolivia. He spent 18 months in the Mato Grosso area and it was during his various expeditions that Fawcett became obsessed with the idea of lost civilizations in this area.

The wild wilderness of the Amazon in Brazil, where Percy Fawcett conducted numerous expeditions ( Wikimedia Commons )

Fawcett describes the city of Z

Fawcett formulated theories of a city he called ‘Z’ in 1912. His conviction was fueled in part by the rediscovery of the lost Inca city of Machu Picchu, in 1911, hidden away in Peru’s Andes Mountains. During his travels, Fawcett also heard rumors of a secret city buried in the jungles of Chile that was said to have streets paved in silver and roofs made of gold. Of Z itself, Fawcett had a specific idea of what the city looked like. In a letter to his son Brian, Fawcett wrote:

I expect the ruins to be monolithic in character, more ancient than the oldest Egyptian discoveries. Judging by inscriptions found in many parts of Brazil, the inhabitants used an alphabetical writing allied to many ancient European and Asian scripts. There are rumors, too, of a strange source of light in the buildings, a phenomenon that filled with terror the Indians who claimed to have seen it.

The central place I call “Z” — our main objective — is in a valley surmounted by lofty mountains. The valley is about ten miles wide, and the city is on an eminence in the middle of it, approached by a barreled roadway of stone. The houses are low and windowless, and there is a pyramidal temple. The inhabitants of the place are fairly numerous, they keep domestic animals, and they have well-developed mines in the surrounding hills. Not far away is a second town, but the people living in it are of an inferior order to those of “Z.” Farther to the south is another large city, half buried and completely destroyed.

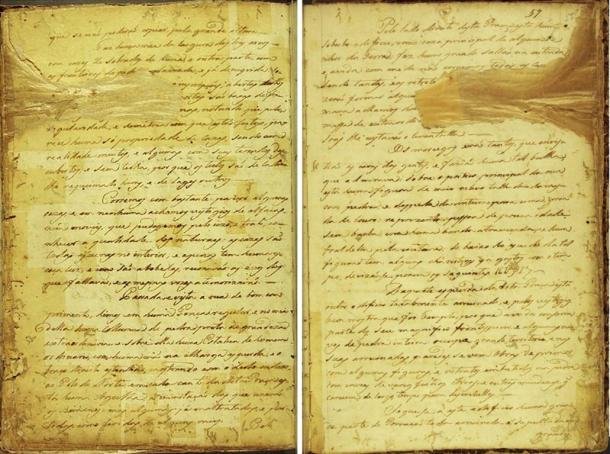

Manuscript 512

In 1920, Fawcett came across a document in the National Library of Rio De Janeiro called Manuscript 512. It was written by a Portuguese explorer in 1753, who claimed to have found a walled city deep in the Mato Grosso region of the Amazon rainforest, reminiscent of ancient Greece. The manuscript described a lost, silver laden city with multi-storied buildings, soaring stone arches, wide streets leading down towards a lake on which the explorer had seen two white Indians in a canoe. On the sides of a building were carved letters that seemed to resemble Greek or an early European alphabet. These claims were dismissed by archaeologists who believed the jungles could not hold such large cities, but for Fawcett, it all came together.

- Archaeologists find untouched ruins in their search for the Lost City of the Monkey God

- The Search for El Dorado – Lost City of Gold

- Have Scientists Finally Discovered the Lost City of Gold?

In 1921, Fawcett set out on his first expedition to find Z. Not long after departing, he and his team became demoralized by the hardships of the jungle, dangerous animals, and rampant diseases. The expedition was derailed, but Fawcett would depart in search of his fabled city later again that same year, this time from Bahia, Brazil, on a solo journey. He traveled this way for three months before returning in failure once again.

The disappearance of Percy Fawcett

Percy’s final search for Z culminated in his complete disappearance. In April 1925, he attempted one last time to find Z, this time better equipped and better financed by newspapers and societies including the Royal Geographic Society and the Rockefellers. Joining him on the expedition was his good friend Raleigh Rimell, his eldest 22 year old son, Jack, and two Brazilian laborers.

On May 29th, 1925, Fawcett and company reached the edge of unexplored territory, staring into jungles that no foreigner had ever seen. He explained in a letter home they were crossing the Upper Xingu, a southeastern tributary of the Amazon River and had sent one of their Brazilian travel companions back, wishing to continue the journey alone. The team got as far as a place called Dead Horse Camp, where Fawcett sent back dispatches for five months and after the fifth month they stopped. In his final dispatch, Fawcett sent a message to his wife Nina and proclaimed “ We hope to get through this region in a few days.... You need have no fear of any failure .” It was to be the last anyone would ever hear from them again.

The expedition had previously stated that they had planned to be gone for around a year, so when two years passed without any word, people began to worry. Numerous expeditions seeking answers were mounted, many of which suffered the same fate as Fawcett. A journalist named Albert de Winton went out in search of his team and was never seen again. In total, 13 expeditions would be launched in an effort to find answers to Fawcett’s fate, and over 100 people would lose their lives or join the explorer to vanish into the jungle. Thousands of people applied to go on these expeditions, and dozens set out looking for them over the next several decades.

- The Lost City of Aztlan – Legendary Homeland of the Aztecs

- The Search for Cibola, the Seven Cities of Gold

The official report from one of the rescue missions said that Fawcett had gone up the Kululene River and was killed for insulting an Indian chief which is the story most believe today. However, Fawcett had always talked about maintaining positive relationships with the indigenous people of the area and the way the natives remember him correlates with what Fawcett has written down. Another possibility is that he and his team died as a result of an accident such as disease or drowning. A third possibility is that they were caught off guard and robbed and killed. There had been a revolution in the area not long before and renegade soldiers had been hiding out in the jungle. On a number of occasions, within months of this expedition, travelers had been stopped, robbed and in some cases murdered by the rebels.

In 1952, the Kalapalo Indians of Central Brazil reported that some explorers had passed through their region and were killed for speaking badly to the children of the village. The details of their account suggested that the victims were Percy Fawcett, Jack Fawcett and Raleigh Rimmell. Following the report, Brazilian explorer Orlando Villas Boas, investigated the supposed area where they were killed and retrieved human bones, as well as personal objects including a knife, buttons, and small metal objects.

The bones underwent numerous tests. However, without the DNA of members of Fawcett’s family, who refused to provide samples, no confirmation could be made regarding the identity of the remains. The bones currently reside in the Forensic Medicine Institute of the University of Sao Paulo.

While Fawcett’s lost city of Z has never been found, numerous ancient cities and remains of religious sites have been uncovered in recent years in the jungles of Guatemala, Brazil, Bolivia and Honduras. With the advent of new scanning technology, it is possible that an ancient city that spurred the legends of Z, may one day be found.

Featured image: Illustration of El Dorado, licensed for reuse. ( TheRavens)

By Bryan Hilliard

References

Lost in the Amazon. United States: PBS Home Video, 2011. Film.

"Secrets of The Dead: Lost in the Amazon." PBS. 2015. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/ajax/printable/?id=829&box=2.

Minister, Christopher. "Francisco De Orellana’s Amazon River Expedition." http://latinamericanhistory.about.com/od/latinamericatheconquest/p/Francisco-De-Orellana-S-Amazon-River-Expedition.htm.

"Secrets of the Lost City of Z." CBSNews. February 10, 2010. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/secrets-of-the-lost-city-of-z/.

Swancer, Brent. "The Mysterious Lost Expedition for the City of Z | Mysterious Universe." Mysterious Universe. August 4, 2014. http://mysteriousuniverse.org/2014/08/the-mysterious-lost-expedition-for-the-city-z/.

Grann, David. "The Lost City of Z: A Quest to Uncover the Secrets of the Amazon." September 19, 2005. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.ancient-origins.net/unexplained-phenomena/lost-city-z-and-mysterious-disappearance-percy-fawcett-003265

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit