Who among us would not have loved to catch a glimpse of the shy, dog-like Tasmanian tiger at night? Or seen the impressively tubby dodo waddling along? But we can’t. These stunning creatures are now extinct … because of us.

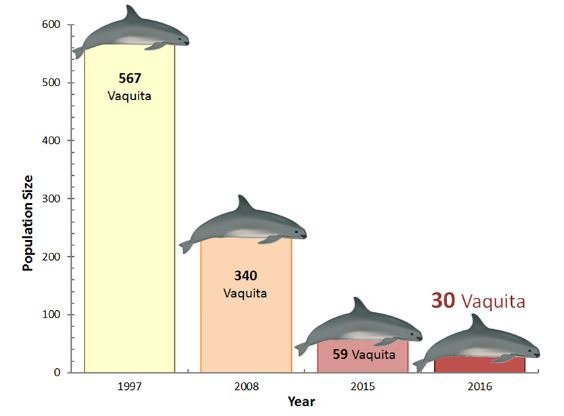

July 7 was International Save The Vaquita Day, where people around the world are hoping to make a last stand against extinction. This is because while extinction does happen naturally, scientists estimate that our actions have sped up the rate of die-out by 100 times or more. Right now, there are more than 25,000 species considered vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered, like the vaquita — an adorable, tiny little porpoise. Whether we like it or not, we can’t save all of those—and that probably includes the vaquita. But hopefully, by looking at species on the brink, we can learn how to keep others from reaching that point of no return. The vaquita should be found swimming the Gulf of California in Mexico. But if you want to jump on a boat in the hopes of spotting one, you’re out of luck. Conservationists estimate that there are less than 30 left. That’s because between 1997 and 2015, their numbers dropped by 92 percent. At this rate, they’ll be gone within a decade—perhaps even by the end of this year. Vaquitas were listed as vulnerable in 1986 because of their limited range and the threat posed by gillnet fishing. That’s a style of fishing where large, vertical nets are hung in the water to ensnare animals as they attempt to push through the mesh. Because of their small size, and similar size to the fish that the fisherman are actually trying to catch, vaquitas often end up entangled, too. In 1990, their status was changed to endangered, and then to critically endangered in 1996. Despite that early warning, it wasn’t until 2005 that the Mexican government created a refuge where gillnets are banned. And that wasn’t enough to stop the decline. So in 2013, incentives were given to switch shrimp fisherman to trawling instead, and a temporary gillnet ban was enacted in 2015, which was made permanent in 2017. The problem is, illegal gillnet fishing continues to this day because totoaba—a type of fish that are also critically endangered—fetch a high price on the black market. So in a last-ditch effort to save the vaquita, scientists have been trying to catch them and put them in a special protective sanctuary for captive breeding. But things aren’t going well so far—one female even died in the process. Plus, there’s concern that there are already just too few of them to have enough genetic diversity.

That’s a measure of how much variation there is in the DNA of a species, and it’s important for avoiding the health consequences of inbreeding. Captive breeding can be somewhat successful, like it has with the Amur Leopard. But even then, there are challenges. The Amur leopard is a subspecies that used to roam around southeastern Russia, the Korean peninsula, and northeastern China, until poachers shot nearly all of them for their gorgeous, thick, spotted fur. Surveys in the late 1990s estimated that between 25 and 40 Amur leopards were left. That ultimately led to the Russian government stepping in by creating a massive protected area—called Land of the Leopard National Park—in 2012. And just giving the leopards enough space has brought their numbers up some. Officials announced that there were 84 adults in the wild in early 2018. Which is great—except that some geneticists fear they’re too inbred to truly recover. Luckily, captive breeding has been effective, as more than 220 Amur leopards live in institutions worldwide. There’s just one catch … and it’s a pretty big one, from a genetics point of view. They are not purebred Amur leopards. The captive population started with just 9 wild leopards, two of which were most likely a similar-looking Chinese subspecies. And that injection of non-relatives means the captive population actually has more variation in its DNA than the wild one. But, they’re not exactly Amur leopards anymore—some geneticists would argue they’re something new, which is what makes this kind of interbreeding, even for conservation, extremely controversial. If the captive bred leopards are reintroduced into the wild population, pure Amur leopards could disappear completely. But if they’re kept separate, the wild population may not recover at all, or may be too inbred to be viable long term. It’s a tough call either way. The leopards are lucky, though, that they’ve got some room for growth in that big park—Javanrhinos are in a similar position, but they don’t have that luxury. Ujung Kulon National Park in Indonesia has 40 to 60 rhinos. Poaching for horns was one of the biggest factors in this species’ demise, but now there are Rhino Protection Units patrolling the park to protect them. The trouble is, Ujung Kulon cannot fit any more rhinos. Already, they’re packed in so tightly that scientists fear diseases could spread quickly enough to speed their extinction. And there are signs that’s already happening, as bacteria from nearby cattle farms seem to be making their way into the rhino population. If that’s not bad enough, there’s also an invasive palm species overtaking the rhino’s preferred food plants, wreaking havoc on what little habitat they have. The situation is so bad that scientists have admitted that they are at an impasse. They’re not sure if the rhinos can be safely relocated even if there was somewhere for them to go. And it’s not clear if they would take to captive breeding or what such a program would need to look like to work—or if there are already too few of them for it to matter. Like with Amur leopards and the vaquita, any efforts to save the rhinos might just be too little too late. These are heartbreaking stories, with a hard lesson. Stopping the extinctions we’re causing means acting early, not waiting until things are dire and hoping a Herculean effort will save the day. Perhaps if gill nets were banned sooner, vaquitas wouldn’t be on the brink of extinction now. Or if Land of the Leopard National Park had been created decades earlier, genetic diversity wouldn’t have been a concern. But conservation, like lots of areas of science, is tricky — partly because it’s not just about the animals. Protecting species also means finding a way to resolve conflicts between them and us. Like, how to make space for the Javan rhino without taking away the livelihoods of neighboring farmers and their families. The power of hindsight lets us see where things went wrong for these species, and it gives us clues as to how we might avoid making the same mistakes going forward.