Ken Schumacher received this story from Barlow after posting a request for reminiscences from people who'd known Neal Cassady. Thanks to Ken for sending this to me, and to John Perry Barlow for giving me permission to include it in Literary Kicks. It is a very beautiful piece of writing, and it also answers a question that had been bugging me for years: why did Barlow spell Neal's name wrong in the title of the song? Turns out there's a simple answer. -- Levi Asher

"Cassidy"

By John Perry Barlow with Bob Weir

Recorded on Ace (Warner Brothers, 1972)

Cora, Wyoming February, 1972

"I have seen where the wolf has slept by the silver stream.

I can tell by the mark he left you were in his dream.

Ah, child of countless trees.

Ah, child of boundless seas.

What you are, what you're meant to be

Speaks his name, though you were born to me,

Born to me,

Cassidy...

Lost now on the country miles in his Cadillac.

I can tell by the way you smile he's rolling back.

Come wash the nighttime clean,

Come grow this scorched ground green,

Blow the horn, tap the tambourine

Close the gap of the dark years in between

You and me,

Cassidy...

Quick beats in an icy heart.

Catch-colt draws a coffin cart.

There he goes now, here she starts:

Hear her cry.

Flight of the seabirds, scattered like lost words

Wheel to the storm and fly.

Faring thee well now.

Let your life proceed by its own design.

Nothing to tell now.

Let the words be yours, I'm done with mine

This is a song about necessary dualities: dying & being born, men & women, speaking & being silent, devastation & growth, desolation & hope.

It is also about a Cassady and a Cassidy, Neal Cassady and Cassidy Law.

(The title could be spelled either way as far as I'm concerned, but I think it's officially stamped with the latter. Which is appropriate since I believe the copyright was registered by the latter's mother, Eileen Law.)

The first of these was the ineffable, inimitable, indefatigable Holy Goof Hisself, Neal Cassady, aka Dean Moriarty, Hart Kennedy, Houlihan, and The Best Mind of Allen Ginsberg's generation.

Neal Cassady, for those whose education has been so classical or so trivial or so timid as to omit him, was the Avatar of American Hipness. Born on the road and springing full-blown from a fleabag on Denver's Larimer Street, he met the hitch-hiking Jack Kerouac there in the late 40's and set him, and, through him, millions of others, permanently free.

Neal came from the oral tradition. The writing he left to others with more time and attention span, but from his vast reserves flowed the high-octane juice which gassed up the Beat Generation for eight years of Eisenhower and a thousand days of Camelot until it, like so many other things, ground to a bewildered halt in Dallas.

Kerouac retreated to Long Island, where he took up Budweiser, the National Review, and the adipose cynicism of too many thwarted revolutionaries. Neal just caught the next bus out.

This turned out to be the psychedelic nose-cone of the 60's, a rolling cornucopia of technicolor weirdness named Further. With Ken Kesey raving from the roof and Neal at the wheel, Further roamed America from 1964 to 1966, infecting our national control delusion with a chronic and holy lunacy to which it may yet succumb.

From Further tumbled the Acid Tests, the Grateful Dead, Human Be-Ins, the Haight-Ashbury, and, as America tried to suppress the infection by popularizing it into cheap folly, The Summer of Love, and Woodstock.

I, meanwhile, had been initiated into the Mysteries within the sober ashrams of Timothy Leary's East Coast, from which distance the Prankster's psychedelic psircuses seemed, well, a bit psacreligious. Bobby Weir, whom I'd known since prep school, kept me somewhat current on his riotous doings with the Pranksters et al, but I tended to dismiss on ideological grounds what little of this madness he could squeeze through a telephone.

So, purist that I was, I didn't actually meet Neal Cassady until 1967, by which time Further was already rusticating behind Kesey's barn in Oregon and the Grateful Dead had collectively beached itself in a magnificently broke-down Victorian palace at 710 Ashbury Street, two blocks up the hill from what was by then, according to Time Magazine, the axis mundi of American popular culture. The real party was pretty much over by the time I arrived.

But Cassady, the Most Amazing Man I Ever Met, was still very much Happening. Holding court in 710's tiny kitchen, he would carry on five different conversations at once and still devote one conversational channel to discourse with absent persons and another to such sound effects as disintegrating ring gears or exploding crania. To log into one of these conversations, despite their multiplicity, was like trying to take a sip from a fire hose.

He filled his few and momentary lapses in flow with the most random numbers ever generated by man or computer or, more often, with his low signature laugh, a heh, heh, heh, heh which sounded like an engine being spun furiously by an over-enthusiastic starter motor.

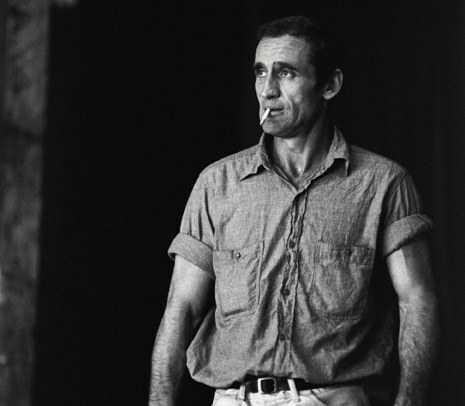

As far as I could tell he never slept. He tossed back green hearts of Mexican dexedrina by the shot-sized bottle, grinned, cackled, and jammed on into the night. Despite such behavior, he seemed, at 41, a paragon of robust health. With a face out of a recruiting poster (leaving aside a certain glint in the eyes) and a torso, usually raw, by Michelangelo, he didn't even seem quite mortal. Though he would shortly demonstrate himself to be so.

Neal and Bobby were perfectly contrapuntal. As Cassady rattled incessantly, Bobby had fallen mostly mute, stilled perhaps by macrobiotics, perhaps a less than passing grade in the Acid Tests, or, more likely, some combination of every strange thing which had caused him to start thinking much faster than anyone could talk. I don't have many focussed memories from the Summer of 1967, but in every mental image I retain of Neal, Bobby's pale, expressionless face hovers as well.

Their proximity owed partly to Weir's diet. Each meal required hours of methodical effort. First, a variety of semi-edibles had to be reduced over low heat to a brown, gelatinous consistency. Then each bite of this preparation had to be chewed no less than 40 times. I believe there was some ceremonial reason for this, though maybe he just needed time to get used to the taste before swallowing.

This all took place in the kitchen where, as I say, Cassady was also usually taking place. So there would be Neal, a fountain of language, issuing forth clouds of agitated, migratory words. And across the table, Bobby, his jaw working no less vigorously, producing instead a profound, unalterable silence. Neal talked. Bobby chewed. And listened.

So would pass the day. I remember a couple of nights when they set up another joint routine in the music room upstairs. The front room of the second floor had once been a library and was now the location of a stereo and a huge collection of communally-abused records.

It was also, at this time, Bobby's home. He had set up camp on a pestilential brown couch in the middle of the room, at the end of which he kept a paper bag containing most of his worldly possessions.

Everyone had gone to bed or passed out or fled into the night. In the absence of other ears to perplex and dazzle, Neal went to the music room, covered his own with headphones, put on some be-bop, and became it, dancing and doodley-oooping a Capella to a track I couldn't hear. While so engaged, he juggled the 36 oz. machinist's hammer which had become his trademark. The articulated jerky of his upper body ran monsoons of sweat and the hammer became a lethal blur floating in the air before him.

While the God's Amphetamine Cowboy spun, juggled and yelped joyous *doo-WOP's,: Weir lay on his couch in the foreground, perfectly still, open eyes staring at the ceiling. There was something about the fixity of Bobby's gaze which seemed to indicate a fury of cognitive processing to match Neal's performance. It was as though Bobby were imagining him and going rigid with the effort involved in projecting such a tangible and kinetic image.

I also have a vague recollection of driving someplace in San Francisco with Neal and a amazingly lascivious redhead, but the combination of drugs and terror at his driving style has fuzzed this memory into a dreamish haze. I remember that the car was a large convertible, possibly a Cadillac, made in America at a time we still made cars of genuine steel but that its bulk didn't seem like armor enough against a world coming at me so fast and close.

Nevertheless, I recall taking comfort in the notion that to have lived so long this way Cassady was probably invulnerable and that, if that were so, I was also within the aura of his mysterious protection.

Turned out I was wrong about that. About five months later, four days short of his 42nd birthday, he was found dead next to a railroad track outside San Miguel D'Allende, Mexico. He wandered out there in an altered state and died of exposure in the high desert night. Exposure seemed right. He had lived an exposed life. By then, it was beginning to feel like we all had.

In necessary dualities, there are only protagonists. The other protagonist of this song is Cassidy Law, who is now, in the summer of 1990, a beautiful and self-possessed young woman of 20.

When I first met her, she was less than a month old. She had just entered the world on the Rucka Rucka Ranch, a dust-pit of a one-horse ranch in the Nicasio Valley of West Marin which Bobby inhabited along with a variable cast of real characters.

These included Cassidy's mother Eileen, a good woman who was then and is still the patron saint of the Deadheads, the wolf-like Rex Jackson, a Pendleton cowboy turned Grateful Dead roadie in whose memory the Grateful Dead's Rex Foundation is named, Frankie Weir, Bobby's ol' lady and the subject of the song Sugar Magnolia, Sonny Heard, a Pendleton bad ol' boy who was also a GD roadie, and several others I can't recall.

There was also a hammer-headed Appaloosa stud, a vile goat, and miscellaneous barnyard fowl which included a peacock so psychotic and aggressive that they had to keep a 2 x 4 next to the front door to ward off his attacks on folks leaving the house. In a rural sort of way, it was a pretty tough neighborhood. The herd of horses across the road actually became rabid and had to be destroyed.

It was an appropriate place to enter the 70's, a time of bleak exile for most former flower children. The Grateful Dead had been part of a general Diaspora from the Haight as soon as the Summer of Love festered into the Winter of Our Bad Craziness. They had been strewn like jetsam across the further reaches of Marin County and were now digging in to see what would happen next.

The prognosis wasn't so great. 1968 had given us, in addition to Cassady's death, the Chicago Riots and the election of Richard Nixon. 1969 had been, as Ken Kesey called it, *the year of the downer,: which described not only a new cultural preference for stupid pills but also the sort of year which could mete out Manson, Chappaquiddick, and Altamont in less than 6 weeks.

I was at loose ends myself. I'd written a novel, on the strength of whose first half Farrar, Straus, & Giroux had given me a healthy advance with which I was to write the second half. Instead, I took the money and went to India, returning seven months later a completely different guy. I spent the first 8 months of 1970 living in New York City and wrestling the damned thing to an ill-fitting conclusion, before tossing the results over a transom at Farrar, Straus, buying a new motorcycle to replace the one I'd just run into a stationary car at 85 mph, and heading to California.

It was a journey straight out of Easy Rider. I had a no-necked barbarian in a Dodge Super Bee try to run me off the road in New Jersey (for about 20 high speed miles) and was served, in my own Wyoming, a raw, skinned-out lamb's head with eyes still in it. I can still hear the dark laughter that chased me out of that restaurant.

Thus, by the time I got to the Rucka Rucka, I was in the right raw mood for the place. I remember two bright things glistening against this dreary backdrop. One was Eileen holding her beautiful baby girl, a catch-colt (as we used to call foals born out of pedigree) of Rex Jackson's.

And there were the chords which Bobby had strung together the night she was born, music which eventually be joined with these words to make the song Cassidy. He played them for me. Crouched on the bare boards of the kitchen floor in the late afternoon sun, he whanged out chords that rang like the bells of hell.

And rang in my head for the next two years, during which time I quit New York and, to my great surprise, became a rancher in Wyoming, thus beginning my own rural exile.

In 1972, Bobby decided he wanted to make the solo album which became Ace. When he entered the studio in early February, he brought an odd lot of material, most of it germinative. We had spent some of January in my isolated Wyoming cabin working on songs but I don't believe we'd actually finished anything. I'd come up with some lyrics (for Looks Like Rain and most of Black-Hearted Wind). He worked out the full musical structure for Cassidy, but I still hadn't written any words for it.

Most of our time was passed drinking Wild Turkey, speculating grandly, and fighting both a series of magnificent blizzards and the house ghost (or whatever it was) which took particular delight in devilling both Weir and his Malamute dog.

(I went in one morning to wake Bobby and was astonished when he reared out of bed wearing what appeared to be black-face. He looked ready to burst into Sewanee River. Turned out the ghost had been at him. He'd placed at 3 AM call to the Shoshone shaman Rolling Thunder, who'd advised him that a quick and dirty ghost repellant was charcoal on the face. So he'd burned an entire box of Ohio Blue Tips and applied the results.)

I was still wrestling with the angel of Cassidy when he went back to California to start recording basic tracks. I knew some of what it was about...the connection with Cassidy Law's birth was too direct to ignore...but the rest of it evaded me. I told him that I'd join him in the studio and write it there.

Then my father began to die. He went into the hospital in Salt Lake City and I stayed on the ranch feeding cows and keeping the feed trails open with an ancient Allis-Chalmers bulldozer. The snow was three and a half feet deep on the level and blown into concrete castles around the haystacks.

Bobby was anxious for me to join him in California, but between the hardest winter in ten years and my father's diminishing future, I couldn't see how I was going to do it. I told him I'd try to complete the unfinished songs, Cassidy among them, at a distance.

On the 18th of February, I was told that my father's demise was imminent and that I would have to get to Salt Lake. Before I could get away, however, I would have to plow snow from enough stackyards to feed the herd for however long I might be gone. I fired up the bulldozer in a dawn so cold it seemed the air might break. I spent a long day in a cloud of whirling ice crystals, hypnotized by the steady 2600 rpm howl of its engine, and, sometime in the afternoon, the repeating chords of Cassidy.

I thought a lot about my father and what we were and had been to one another. I thought about delicately balanced dance of necessary dualities. And for some reason, I started thinking about Neal, four years dead and still charging around America on the hot wheels of legend.

Somewhere in there, the words to Cassidy arrived, complete and intact. I just found myself singing the song as though I'd known it for years.

I clanked back to my cabin in the gathering dusk. Alan Trist, an old friend of Bob Hunter's and a new friend of mine, was visiting. He'd been waiting for me there all day. Anxious to depart, I sent him out to nail wind-chinking on the horse barn while I typed up these words and packed. By nightfall, another great storm had arrived. We set out for Salt Lake in it, hoping to arrive there in time to close, one last time, the dark years between me and my father.

Grateful Dead songs are alive. Like other living things, they grow and metamorphose over time. Their music changes a little every time they're played. The words, avidly interpreted and reinterpreted by generations of Deadheads, become accretions of meaning and cultural flavor rather than static assertions of intent. By now, the Deadheads have written this song to a greater extent than I ever did.

The context changes and thus, everything in it. What Cassidy meant to an audience, many of whom had actually known Neal personally, is quite different from what it means to an audience which has largely never heard of the guy.

Some things don't change. People die. Others get born to take their place. Storms cover the land with trouble. And then, always, the sun breaks through again.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.litkicks.com/BarlowOnNeal

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit