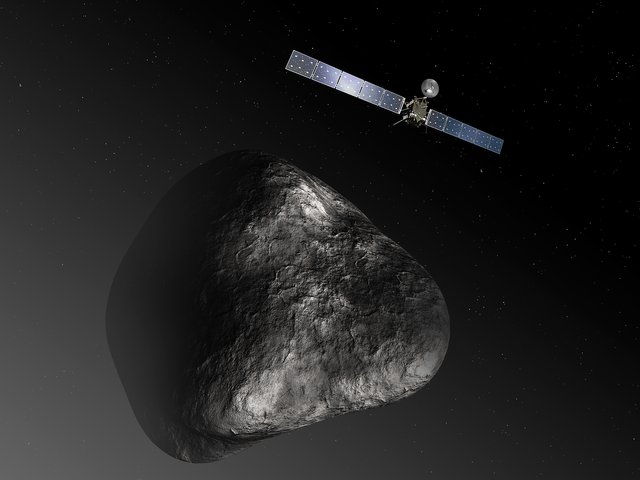

A couple of years ago I was working at a (now defunct) breaking news site, covering science and technology developments. One of my favorite stories from that time was the Rosetta mission, spearheaded by the European Space Agency, to send a satellite to a comet and then land a probe on its surface.

image courtesy ESA

If you're a space exploration nerd like me, you were probably doing backflips back in 2014 when Rosetta made its fateful rendezvous with Comet 67P. You were also probably pretty bummed when Philae, Rosetta's little landing craft, ended up bouncing off the comet's surface and then coming to rest far off-course a couple of hours later in a location that meant it couldn't use its solar panels effectively enough to power itself for very long. Sure, we got a short reprieve in the summer of 2015, when 67P ended up closer to the sun and Philae came out of hibernation briefly, but the truth is that once it went dark once more, most science geeks had written off ever hearing from it - or even finding it - ever again.

Well that's all changed. Barely a month before the Rosetta mission was slated to end, the satellite's onboard OSIRIS camera snapped a curious little picture of the surface of 67P.

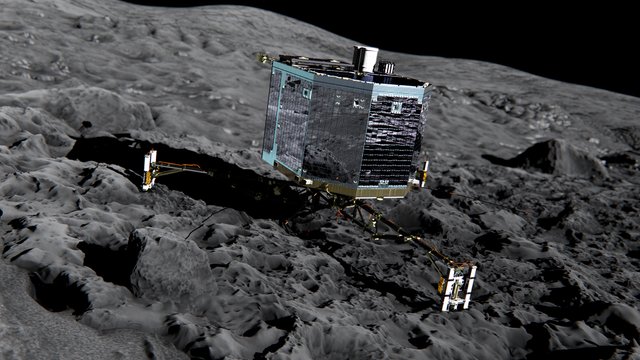

image courtesy ESA

It's blurry - it was taken from nearly 3 kilometers from the surface, after all - but it's unmistakable: that's little Philae, splayed on its side after landing. Either that, or some other space agency snuck out and landed something on 67P while the rest of us weren't watching.

Seems a pretty obvious find, doesn't it? What the hell took the ESA so long to locate Philae? Well, let's put it into perspective - Philae is about the size of a washing machine. 67P is made up of two lobes of rock - the small lobe, the one that Philae landed on - is a hunk of frozen rock measuring 2.5 km by 2.5 km by 2 km. The surface isn't exactly smooth, either - it's pockmarked worse than a teenage acne sufferer. Plus, the whole thing rotates on its axis about every 12 hours, plunging vast swathes of the comet's surface into and out of darkness. Considering Rosetta has been looking everywhere across 67P for Philae, it's a wonder the lander was ever found at all!

Let's take a bigger look at the photograph that located Philae.

image courtesy ESA

Let's play a game of interplanetary Where's Waldo. Do you see Philae in that image? Look at the far right side, about halfway down. There it is, in the shadow of that big boulder - our little missing lander. Talk about a needle in a haystack - a frozen, dirty, massive haystack hurtling through space, offgassing water vapor and God knows what else.

Actually, we know what else. Comet 67P has been giving off water, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, ammonia, methane, methanol, sodium, and magnesium gas. Part of why we know this is because Philae, even though it landed on its side, managed to complete nearly all of its initial mission. Meanwhile I can't even get my Roomba to go under the couch without getting caught on the edge of the rug.

Thanks, Roomba. Image courtesy Flickr user Bob

This is a massive feat of aerospace engineering - bolstered by more than a little bit of luck. It bodes well for the future, when we're all living on asteroids and comets after fleeing our dying planet because we polluted the shit out of it.

Meanwhile, Philae and Rosetta are set to be reunited at the end of the month. The satellite is scheduled to make a one-way trip to the surface of 67P on September 30th, collecting and sending data all the way up until the end. I always thought it was ironic that we take such care to construct these space exploration vehicles, pour millions in R&D costs into them so we can send them out safely into the depths of the cosmos, do our best to gather as much information as possible, and then just crash the shit out of them in the end. Reward for a job well done I suppose.

Whatever happens, Philae and Rosetta have ensconced their place in history. It might not have been as flashy as sending a man to the moon, but the story of the Little Lander that Could is still pretty damn cool.

image courtesy ESA