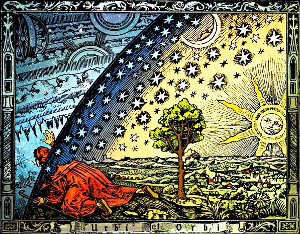

IF YOU SPEND ANY TIME at all reading about mysteries or the occult, you will have seen this illustration (detail above). Although it has no official title, it's instantly recognisable: a philosopher breaks through the barrier of the material world, and is awestruck as he peers into the hidden workings of the Universe.

Surely, this iconic image must be from some ancient book of secret wisdom? What is the now-forgotten teaching that it originally illustrated? As it happens, there is a mystery surrounding the origin of this celebrated picture – but it's not the one you might expect.

Part One: Portrait without a Background

The picture is known as "The Flammarion Engraving," because it first appeared in The Atmosphere, an 1888 book by French astronomer and author Camille Flammarion (1842 - 1925). Flammarion, by the way, is one of the Grand Old Men of strange phenomena, and wrote some very interesting books about parapsychology.

The engraving only became famous in 1959, when it was reproduced in "Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen In The Skies," by Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung. Since then, it has proliferated throughout the literature of the strange and uncanny. I'm using a coloured version in this Steemit post, although the original is black and white.

On close inspection by newly-interested art experts, it turned out that the Flammarion Engraving was not Mediaeval, as had been thought, but was a 19th-Century imitation of Mediaeval styles.

No-one is sure who created the engraving for Flammarion, but since Flammarion had served as an engraver's apprentice in his youth, and created numerous original engravings as an adult, Flammarion himself has to be the prime suspect by anyone's reckoning.

Incidentally, Flammarion (pictured above left, using his telescope) never claimed that the engraving was an authentic Mediaeval image, so it's unfair to describe the picture as a forgery or hoax.

This still leaves a considerable puzzle. Where did the engraver (whoever he or she was) get the idea for such a memorable image?

Part Two: The Puzzle PiecesThe picture seen immediately below is a woodcut by Hans Weiditz, created in 1532 to accompany an edition of Petrarch. Like the Flammarion Engraving it has no formal title, but I'm going to call it "The Apocryphal Nature of Life" because that was the name given to it by the antique print dealer among whose stock I found it.

That title is immediately and obviously appropriate. As you can see, a seeker after knowledge has pierced the material world and is being given the secrets of Creation itself. Does this sound familiar? It does, and the image itself is strangely reminiscent of the Flammarion Engraving. Just a glance at each indicates overwhelmingly that there's a relationship between the two.

The key figure in each is the philosopher with his back turned, and his arms outstretched as he reaches for the secrets of the Heavens (all of which are to the left of the image). The Sun and the Moon, both with human faces, visible in the sky at the same time (in the right-hand half of the image). In the middle of each image, we have a pastoral landscape stretching back to the horizon – although the artists' depictions of that scenery are very different.

Compositionally, these pictures arouse suspicion that there is a connection between them. And when we look closer at the key matching details, that suspicion hardens into certainty. Just one of these features on its own might be considered coincidental. Taken together, the idea of coincidence can be dismissed.

First and foremost, the philosophers themselves are strikingly similar (see my animation, right). The rumpled robe and the broad-crowned hat are obvious parallels.

More subtle are the outlines of the right-hand side of each figure, in each case created by the folds of the robes against the torso and bent leg.

Even subtler still, the hand on the right of the figure in the Flammarion Engraving is almost an exact mirror image of the hand on the left of the Weiditz woodcut.

And yes, mirrors and panes of glass were an everyday tool in the copyist's trade for centuries, which is why so many old engravings and woodcuts also exist in "flipped" versions.

When we turn to figures of the Sun and Moon, again we find close relationships between Weiditz and Flammarion. The Sun was often given a human face by illustrators, so perhaps the similarities here aren't as striking at first glance.

But what will dawn on you as you watch my animation (pictured left) is each Sun's deadpan expression. No beaming smiles here – he hasn't got his hat on and he isn't out to play.

The Moon, however, is the clincher. As you can see from my animation (pictured right) the two are pretty much identical. The Flammarion engraver has added a lot more fine detail, but the outlines are a near-perfect match. (Yes, I've flipped the Flammarion Moon left-to-right; see my remark about copyists' use of reflective glass, above.)

One final detail, however, is a surprise. The Flammarion Engraving has provably lifted from an engraving by an artist other than Weiditz. In the top-left part of the Flammarion Engraving, showing the wheels and spheres of the world beyond, you can see an odd-looking structure resembling a collision between two cartwheels. It looks oddly out-of-place in the celestial realms. But it isn't out-of-place at all if you're familiar with old illustrated Bibles.

It's supposed to represent a "wheel within a wheel", and it relates to the visions of the Prophet Ezekiel.Pre-modern illustrators seem to have had a hard time visualising what Ezekiel was describing. You or I would think of something like a spiral, or rings of concentric circles, all turning in different directions like something seen through a kaleidoscope.

But nope, Ezekiel specified "wheels", and so he obviously meant "wheels". The result was that generations of European illustrators turned out the same weird idea of two cartwheels merged together to form a very rudimentary spherical framework. Perhaps this had to do with working in an age when the Bible was taken very literally, and you could end up accused of blasphemy or worse if you took too many liberties with God's infallible word.

I can now pinpoint the exact source of the "wheel within a wheel" seen in the Flammarion Engraving (animation, right).

As shown below, it's a depiction of Ezekiel's visions by an unknown artist, which I think must be from the early Renaissance. Flammarion's engraver has reversed the image (again), added some spokes, and got rid of the eyeballs on the wheel rims mentioned by Ezekiel. But he hasn't changed the slightly "flared" spokes, or improved on the very vague way that the spokes meet in the centre.

Presumably, the Flammarion engraver was a bit stuck for ideas about how to depict the secrets of the Universe (as perceived by the philosopher, peering into the unknown).

So he turned to his books to look for inspiration, and where better to get a glimpse of God's wonders than the Prophet Ezekiel?

Pulling a volume of Bible woodcuts from the shelf, he found just what he was looking for, and the baffling "wheel within a wheel" detail filled a troublesome empty corner in his engraving.

Part Three: Conclusion – and a ClueSo, to recap, the main sources for the beautiful and enigmatic Flammarion Engraving have now been identified. They are "The Apocryphal Nature of Life" (1532) by Hans Weiditz and "The Fiery Chariot of Ezekiel" by an unknown Renaissance illustrator. This knowledge doesn't change my view that the Flammarion Engraving is a work of near-genius, and it shouldn't spoil anyone else's admiration either. The Flammarion engraver made something unexpected and magical from very unpromising source material. And the creative process is something that is still a genuine mystery of nature that confounds scientists and philosophers to this day.

Speaking of the mysteries of the human mind, I can't resist pointing out that there's a nice sort of synchronicity in the Flammarion Engraving's "quotation" of a picture of Ezekiel's prophetic visions. The Flammarion Engraving only became famous when it was reproduced in Jung's book about the psychosocial significance of "flying saucers"; and the things described by Ezekiel over 2,000 years ago are often cited by UFO believers as evidence that extraterrestrials visited Earth in ancient times. This is a connection that will no doubt intrigue lovers of odd coincidences.

Finally, I can't prove it, but I believe another tell-tale detail shows that the mystery engraver was indeed Camille Flammarion himself. That detail is the crescent moon. In life, the illuminated crescent always faces toward the Sun, but Weiditz had depicted the opposite – which is impossible. A respected astronomer like Flammarion would never have allowed such a schoolboy error to appear in his own work.

⦿ All Rights Reserved

You can read part two of this story here