CARACAS, Venezuela – Even at Bogotá airport in Colombia, the closest major capital city to Venezuela, a look of curiosity comes over the faces of staff when you tell them you are heading to Caracas.

Entry visas into Venezuela remain fairly accessible, although journalists are not allowed without a special visa. Although I claimed I was there as a tourist, this seemed far-fetched even to the likely pro-government immigration authorities. “What is the real motive of your visit?” the officer asked me. “Seeing my girlfriend,” I replied.

She smiled. “Welcome to Venezuela.”

As you travel down from Simon Bolívar International Airport into the city center, the difference between Caracas and Bogotá – formerly one of the world’s major drug war battlegrounds – is stark.

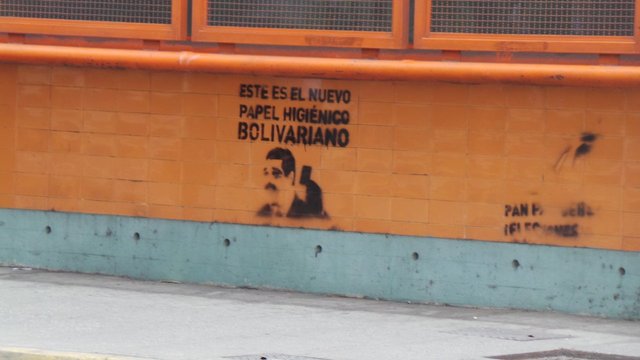

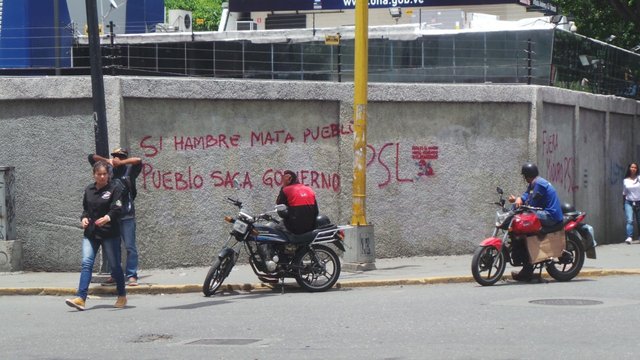

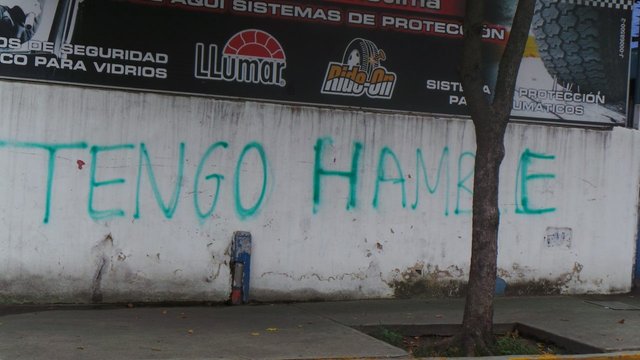

Armed police stand on almost every street corner. Every physical space is dedicated to promoting the success of the late Hugo Chávez’s socialist revolution and Nicolás Maduro’s authoritarian regime. The opposition undermines official government propaganda with its own graffiti, effectively accusing the regime of destroying the country with the highest oil reserves in the world.

The rise in anti-government messaging stands out compared to my visit last November. Pro-government propaganda shares the streets with graffiti denouncing the regime on nearly every block.

“This is the new Bolivarian toilet paper” – a reference to Maduro’s proposed changes to the Venezuelan constitution, rejected by the people in a vote last year. Maduro is depicted holding a pocket constitution.

“If hunger kills the people, the people will take out the government.”

A billboard calls for the release of opposition Leopoldo López, who was imprisoned by the regime in 2014 for organizing a peaceful assembly against Maduro.

Nearly every day, anti-government marches take place across Venezuela, nearly all of which attract violence. So far, as many as 84 protesters have been killed since daily protests began in late March, as police use water cannons, rubber bullets, and smoke bombs to control the situation.

Protests have the feel of an out-of-control soccer crowd. There is a feeling of solidarity among people, most of whom are wearing Venezuelan flags. On the side of the street, salesmen sell what can only be described as protest merchandise, including Venezuelan flags, horns, and t-shirts.

Below, the shirts read from left to right: “S.O.S. Venezuela;” “Whosoever Tires Will Lose;” “Resistance: Don’t Surrender!”

Closer to police and military barriers, the protests become more tense, with the menace of violence constantly present. Many of those protesting are boys and young men in their mid-teens.

“This is a fight for our families, for our future,” a group of masked protesters tell me. “We will risk our lives every day for as long as it takes to bring down this dictatorship.

A group of young protesters pump themselves up as they prepare to face off with police.

On a visit to the Universidad Central de Venezuela, the country’s biggest university, something seemed not quite right. The university itself seems like any other, with department buildings scattered around a campus, as well as grandiose facilities such as sports stadiums and a stunning concert hall.

Yet, despite it being a Wednesday, there are barely any students around. “The situation is too serious right now for students to dedicate sufficient time to studying,” English professor Lilliana Céspedes tells me. “Many prioritize attending anti-government marches or trying to earn money to support their families. During some of my classes, just a handful of students turn up.”

One of the most frustrating things about trying to understand Venezuela is the high level of security at places the regime would like to hide. As I enter a government-run supermarket, security guards check my pockets to see what I am carrying. They find my camera. “No photos here,” they say. A similar routine takes place on the way out.

I also tried my luck at a Venezuelan state hospital, although this time armed guards asked me to put the camera away. Nearly every public place in Caracas is guarded by police keeping a watchful eye over the situation. Most are very meagerly paid, but still officially remain supportive of the government.

Sitting in a hospital waiting room, armed guards soon ask me to put away my camera. Failing to comply would likely mean facing arrest.

Amid the crisis, some Venezuelans have accused others of not doing enough to fight the Maduro regime. “The only way I see out of the current regime is a military coup,” my taxi driver, Nelson Álvarez, tells me. “Some people have accused me of indifference towards the current political situation, but I have a family to look after. No matter how many or how violent the opposition protests, the key to bringing down this government are the military.”

Everything about Venezuela suggests this is a nation on the brink of collapse. Whether it is the ongoing violence, the extreme poverty, or the enormous piles of garbage in the street, nothing is working as it should be. In January, inflation reached over 800 percent, while some analysts predicting it could reach 1500 percent by the end of the year. Even at one of the city’s most exclusive hotels, breakfast offerings remain scarce and electricity and internet connection regularly cut out.

Thousands of notes are now required to buy anything of value. However, the government recently introduced higher denominations.

Many streets are covered in landfill. People can be regularly seen searching through garbage for scraps.

“I’m Hungry”

While some still solely blame the current crisis on the collapse in oil prices in 2012, a vast majority of Venezuelans believe the country needs serious economic reform. After 17 years of hardcore socialism, egged on by left-wing elites around the world, many in leadership appear hesitant to accuse the socialist system itself – and not the people running it – of being the problem.

Many within the opposition’s leadership structure are members of the Socialist International (SI). Popular Will, the party led by Leopoldo López before his arrest, belongs to the SI. López’s colleagues often find it easier to lay the blame at Maduro’s feet and call for elections, rather than demand a free, capitalist society, rebuilt from the ground up.

Yet the students and street protesters, who have put their lives on pause to fight Maduro, seem to understand that the institutional rot goes way beyond Maduro.

As one student put it to me: “Chávez succeeded in creating an equal society by making everyone poor.”

...Thanks for watching...

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.breitbart.com/national-security/2017/06/12/exclusive-inside-venezuela-socialist-haven-brink-total-collapse/

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you for sharing this. It is so very important to get this out and let people see it. Please start putting your BTC address at the bottom of your articles :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

BTC address ?

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Yes. If you publish your Bitcoin address, or another cryptocurrency address, we can tip you or donate to you for your work.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

its ok my friend no payment needed :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

It is very good work.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

meep

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit