As a boy, Ben Carson watched his father walk out on his family, closing the door on a life the 8-year-old would never know again. Through periods of heartbreak, fear and financial struggle, his mother, Sonya Carson, provided for Ben and his brother. A determined woman with only a third-grade education, she insisted her sons see their potential and that they never let circumstances get them down. She taught them that education would change their lives.

Ben took on the challenges, devoting himself to a life of learning and achievement, overcoming adversity on his path, to become a world-renowned neurosurgeon. Dr. Ben Carson never forgot his mother’s early lessons.

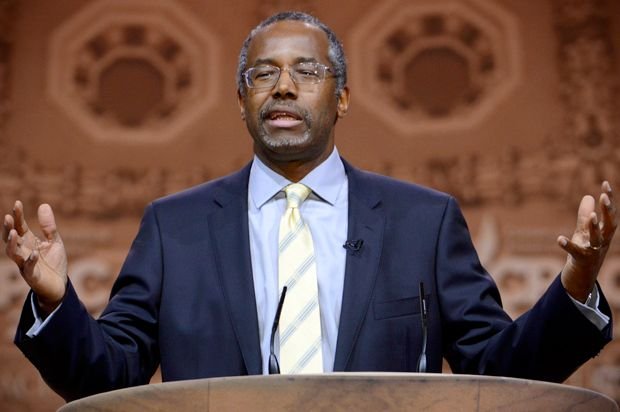

As the director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Carson, 57, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his groundbreaking contributions to medicine and his efforts to help America’s youth fulfill their potential.

Even at 8, when his father left, Carson knew he wanted to be a doctor, he writes in his autobiography, Gifted Hands. When Sonya Carson moved her sons from their modest house in Detroit to live with her brother and his wife in Boston, she scrimped and sacrificed so they could return. When they did, they had to settle for Detroit’s downtown housing projects—but at least they were home.

Sonya Carson knew the world held more hope for her boys than the ghetto offered. She struggled to support the family without relying on government assistance.

Ben was lost, hopelessly behind in his schoolwork in a school that was competitive. The other kids picked on him and called him “dummy.” Ben lashed back with his fists. He resigned himself to thinking he was stupid.

With both boys’ grades suffering, Sonya took away the TV and replaced it with library cards. She required both sons to read two books a week and turn in book reports. The boys left the reports on the table for her before going to bed. In the morning, they found red check marks on their papers, signifying her approval.

The boys did not realize until they were adults that their mother couldn’t read. Last summer, she beamed as President Bush bestowed the Medal of Freedom on her son and acknowledged her. “Even in the toughest times, she always encouraged her children’s dreams,” Bush said. “She never allowed them to see themselves as victims. She never, ever gave up.”

Carson gives his mother much of the credit for his success. “If my mother had not been such a positive influence in my life, and had not stressed education as much as she did, I would definitely not have made it into medicine,” he said. “I probably wouldn’t have found my way to college at all.”

Reading changed Ben Carson’s life. Books became an escape for him. He enjoyed reading about animals and nature and found self-confidence in his newfound knowledge. As a fifth grader, he could identify the rocks he found along the railroad tracks on his walk home from school. His brother, Curtis, who grew up to become an engineer, kidded Ben about the rocks. But Ben was not deterred.

Also in fifth grade, an eye test revealed Ben badly needed glasses. With his new love for knowledge and a shiny pair of glasses, his world was changing. As his grades improved, the name-calling stopped. Other kids began to respect him and even ask for help with their schoolwork. He knew he could achieve anything he set his mind to—and that knowledge helped him make his dreams come true. “As my mother would tell me,” he says, “ ‘Give your best, Ben Carson. Settle for nothing less than doing your best for yourself and others.’ ”

His hard work continued through high school and he won a scholarship to Yale, followed by medical school at the University of Michigan. At 33, Carson became the youngest physician to head a major division at Johns Hopkins.

Carson now concentrates on traumatic brain injuries, brain and spinal cord tumors, and neurological and congenital disorders. In 1987, he led a team of 69 medical professionals in achieving a first: successfully separating conjoined twins who were attached at the back of their heads.

He continues to revolutionize neurosurgery with advanced techniques such as hemispherectomies, removing half the brain to treat seizure disorders. The radical procedure is performed, usually on children, when all other treatment options have been exhausted. Since the 1980s, Carson has refined and developed new approaches to these delicate surgeries, increasing universal success rates.

The doctor believes that encouraging people to succeed in life is as important as the work he does in the operating room. “The neurosurgery provides a platform for me to help people recognize that the person who has the most influence on them and their success is themselves,” he says. “If I didn’t do all that I do as a doctor, then nobody would want to hear what I have to say.”

He views education and knowledge as central to a successful life. “Acquiring knowledge makes you an incredibly valuable person,” Carson says. “And reading, because that exercises your mind, is like exercising your mind with weights.”

Throughout his early years, Carson relied on the kindness and guidance of mentors. One of his earliest was an elementary school science teacher who sparked his interest in research and studying organisms under a microscope. “From that point on, I always knew I wanted to be a doctor,” he says.

A mentor who influenced Carson greatly during his last two years at medical school was Dr. James Taren, a renowned neurosurgeon, who stressed that patients deserve a doctor’s full attention, that there is no “time off” when someone’s life hangs in the balance. “The person in the bed isn’t just a patient, but a human being with a name and a life outside the hospital,” Carson says.

“There are definitely not enough mentors today,” he says. “That’s one of the reasons I try to encourage people to look at their sphere of influence and to seek out young people. If you mentor someone and get them going, and then they do that for someone else, it has a ripple effect. And I can’t overemphasize how much help we need mentoring young people today.”

In 1994, Carson and his wife, Candy, founded the Carson Scholars Fund, a nonprofit organization rewarding students in fourth through 11th grades who strive for academic excellence and demonstrate a strong commitment to their communities. “We want these scholars to think that they are world-beaters,” he says. “You take a fourth-, fifth- or sixth-grader and give them all the attention for academic achievement and humanitarian qualities and you have started something.”

The Carson Scholars Fund has awarded more than 3,400 college scholarships. Through annual golf tournaments, galas and other events, along with the help of a star-studded board of directors, the organization continues to raise money to expand the program. His dream is to have a Carson Scholar in every school in the country.

“Once you begin to understand and realize what you are capable of, the whole world changes,” he says. “When I was in the fifth grade and I thought I was a dummy, I was relatively depressed. That’s probably why I was angry all the time. But once I discovered through reading that I could control my own future, it was like someone had lifted a veil; I couldn’t get enough knowledge at that point. Everything that was new was exciting to me, and I began to think about what I was going to do, how I was going to change the world.” He pauses and seems to reflect on his profound childhood transformation before finishing his thought. “I had the same brain, just a different attitude.”

www.chicagotribune.com/topic/politics.../ben-carson-PECLB0015321-topic.html

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.success.com/article/never-give-up

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit