In the early 18th century, when he was still resident at Cambridge University, Isaac Newton composed a new chronology of the world, one which broke radically with the Biblical timeline that had held sway in the West for more than a millennium. He later drafted a short treatise on the subject, which has remained largely unknown and unread to this day. The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended was published posthumously in 1728. This critique of Biblical chronology—at that time, the bedrock of Western history—is a startling anticipation of the Short Chronology, which I have been promoting on this blog for several years.

Chapter 6

The fifth chapter of the The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended is a description of the Temple of Solomon, based for the most part on the Book of Ezekiel. As this chapter contains nothing of chronological interest, let us pass over it and consider instead the following chapter, which is entitled Of the Empire of the Persians.

This chapter, the last in the book, brings Newton’s chronology back in line with the conventional chronology that is found in our modern textbooks. Initially, however, these two chronological frameworks are still at variance. The received chronology is largely informed by archaeological discoveries made in the last few centuries—for example, the Chronicle of Nabonidus—whereas Newton’s chronology is based primarily on Biblical accounts, supplemented with Classical sources.

According to mainstream historians, Cyrus the Great established the Persian Empire in 550 BCE, when he dethroned Astyages, the last ruler of the Median Empire, at the Battle of Pasargadae. According to Newton, however, Cyrus’s immediate predecessor was Darius the Mede, a shadowy figure mentioned in the Book of Daniel but regarded by modern historians as a literary fiction. Newton dates his overthrow by Cyrus to 536 BCE.

Biblical Evidence

In Newton’s chronology, the Bible trumps all other sources. When compiling his timeline of the Persian Empire, however, he was forced to draw on Greek and Latin sources, as the Bible was often silent on important details relating to Persian chronology:

I have hitherto stated the times of this Monarchy out of the Greek and Latin writers: for the Jews knew nothing more of the Babylonian and Medo-Persian Empires than what they have out of the sacred books of the old Testament; and therefore own no more Kings, nor years of Kings, than they can find in those books. (Newton 356)

For assistance, Newton first turned to the Seder Olam Rabbah, a rabbinical chronology compiled, it is thought, in the 2nd century CE. The last three chapters of this treatise (Chapters 28, 29 and 30) are based primarily on the Books of Daniel, Ezra & Esther, and Nehemiah. Newton’s reading of this text and the corresponding passages in the Bible leads him to construct the following timeline for the late Babylonian, Median and early Persian eras:

| King | Length of Reign |

|---|---|

| Nebuchadnezzar | 45 |

| Evil-Merodach | 23 |

| Belshazzar | 3 |

| Darius the Mede | 1 or 2 |

| Cyrus | 3 |

| Ahasuerus = Xerxes | 14 |

| Darius Hystaspis = Artaxerxes | 36 |

So that the Persian Empire from the building of the Temple in the Second year of Darius Hystaspis, flourished only thirty four years, until Alexander the great overthrew it: thus the Jews reckon in their greater Chronicle, Seder Olam Rabbah. (Newton 357)

In order to reconcile the Biblical records with those of secular historians, the authors of the Seder Olam Rabbah conflated various historical characters:

Thus all the Jews conclude the Persian Empire with Artaxerxes Longimanus, and Darius Nothus, allowing no more Kings of Persia, than they found in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah; and referring to the Reigns of this Artaxerxes, and this Darius, whatever they met with in profane history concerning the following Kings of the same names: so as to take Artaxerxes Longimanus, Artaxerxes Mnemon and Artaxerxes Ochus, for one and the same Artaxerxes; and Darius Nothus, and Darius Codomannus, for one and the same Darius. (Newton 357)

Chapter 30 of the Seder Olam Rabbah goes even further than this by actually conflating Cyrus, Darius and Artaxerxes (Guggenheimer 255-256). Cambyses is not mentioned in either the Bible or the Seder Olam Rabbah. Newton was dissatisfied with this approach:

These accounts being very imperfect, it was necessary to have recourse to the records of the Greeks and Latines, and to the Canon recited by Ptolemy, for stating the times of this Empire. Which being done, we have a better ground for understanding the history of the Jews set down in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, and adjusting it; for this history having suffered by time, wants some illustration. (Newton 358)

Newton believed that he could do better than the rabbinical scholars by interpreting the Biblical texts in the light of the Greek and Latin secular sources. His arguments are quite involved and detailed, and take up eighteen pages (Newton 356-373). For his computations, he allows about 27 or 28 years only to a Generation by the eldest sons (Newton 363). He supplements what can be gleaned from Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles with Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews.

The result is that the remainder of Newton’s chronology is more or less in line with what is commonly accepted today. Here and there one finds a discrepancy of a single year, but otherwise the two chronologies are essentially the same:

| Ruler | Newton | Mainstream |

|---|---|---|

| Cyrus II | 536-529 | 550-530 |

| Cambyses II | 529-521 | 530-522 |

| Bardia (Smerdis, Mardus, Gaumata) | 521 | 522 |

| Maraphus & Artaphernes | 521 | - |

| Darius I | 521-485 | 522-486 |

| Xerxes I | 485-464 | 486-465 |

| Artabanus | 464 | - |

| Artaxerxes I | 464-424 | 465-424 |

| Xerxes II | 424 | 424 |

| Sogdianus | 424 | 424-423 |

| Darius II Nothus | 424-405 | 423-404 (or 405) |

| Artaxerxes II Mnemon | 405-359 | 404 (or 405)-358 |

| Artaxerxes III Ochus | 359-336 | 358-338 |

| Artaxerxes IV Arogus | 338-336 | 338-336 |

| Darius III Codomannus | 336-331 | 336-330 |

Maraphus and Artaphernes

A word or two should be said about Maraphus and Artaphernes, who are alleged by Newton to have reigned in succession for a few days before the accession of Darius the Great. In his text, Newton does not cite any source for this piece of information, but it derives from a single disputed line in The Persians, the Greek tragedy by Aeschylus. At one point in the drama, the Shade of Darius appears to his widow Atossa (the mother of Xerxes I) and recalls the succession of Persian Emperors:

Third, after him, Cyrus, blest in his fortune, came to the throne and stablished peace for all his people. The Lydians and Phrygians he won to his rule, and the whole of Ionia he subdued by force ; for the gods hated him not, since he was right-minded. Fourth in succession, the son of Cyrus ruled the host. Fifth in the list, Mardus came to power, a disgrace to his native land and to the ancient throne ; but he was slain in his palace by the guile of gallant Artaphrenes, with the help of friends whose part this was. [Sixth came Maraphis, and seventh Artaphrenes.] And I in turn attained the lot I craved.

(The Persians 768-779, Smyth 175-177)

The editor and translator Herbert Weir Smyth placed line 778 within square brackets:

Sixth came Maraphis, and seventh Artaphrenes (Smyth 175-177)

In a footnote, Smyth adds the comment:

This interpolated or corrupt verse possibly comes from a variant list of the conspirators against the Smerdis (in l. 774 called Mardus), whom the Magian rebels planned to put in place of the real prince of that name, who was slain by his brother Cambyses. The name Maraphis does not occur elsewhere in connection with this event, and neither he nor Artaphrenes was ever king. Herodotus names Intaphernes as the chief conspirator against the false Smerdis. (Smyth 177 fn 1)

Artabanus

Another discrepancy between Newton’s chronology and the currently accepted one concerns the figure of Artabanus:

[Xerxes I] Reigned almost twenty one years by the consent of all writers, and was murdered by Artabanus, captain of his guards; towards the end of winter, Anno Nabonass. 284 [= 464 BCE]. Artabanus Reigned seven months, and upon suspicion of treason against Xerxes, was slain by Artaxerxes Longimanus, the son of Xerxes. (Newton 354)

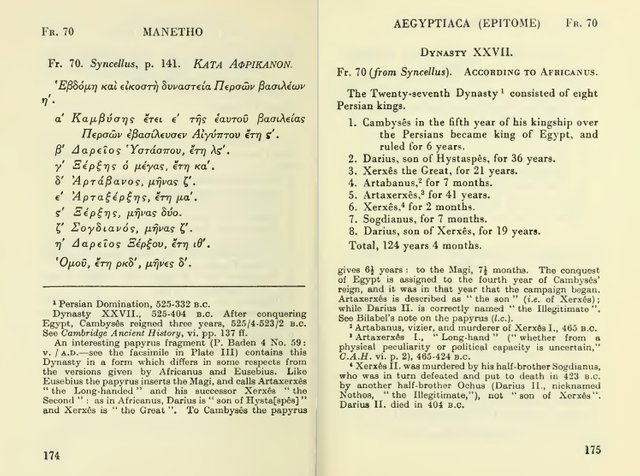

Modern historians accept that Artabanus, one of Xerxes’ foremost officials, assassinated Xerxes, but his motives and the subsequent sequence of events are disputed. He is not generally recognized as ever having sat upon the throne, even for a few months. Newton’s source for the claim that Artabanus reigned for seven months is Sextus Julius Africanus, a Christian historian, whose Chronographiai, a history of the world in five volumes, survives only in fragments. One of these, Fragment 70, was preserved by the Byzantine scholar George Syncellus, and is itself a fragment of the Aegyptiaca by the Egyptian priest and historian Manetho. Manetho placed Artabanus in the 27th Dynasty, which comprised the Persian rulers of Egypt from Cambyses to Darius II:

Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy’s Royal Canon omits Maraphus, Artaphernes, Artabanus, Xerxes II and Sogdianus, and refers to Artaxerxes III and IV as Ωχος (Ōchos) and Ἀρωγος (Arōgos) respectively. It also assigns some reign lengths that are at odds with Newton’s chronology:

| King | Length of Reign |

|---|---|

| Cyrus | 9 |

| Cambyses II | 8 |

| Darius I | 36 |

| Xerxes | 21 |

| Artaxerxes I | 41 |

| Darius II | 19 |

| Artaxerxes II | 46 |

| Ōchos (Artaxerxes III) | 21 |

| Arōgos (Artaxerxes IV) | 2 |

| Darius III | 4 |

Shahnameh

Newton now turns to another source of information concerning the early history of the Persians: the Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, an epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi in the late 10th and early 11th centuries CE. The Shahnameh is Iran’s national epic. Ferdowsi’s principal source was a Pahlavi (Middle Persian) work, known as the Xwadāynāmag, or Book of Kings, which was written in the 7th century CE. Ferdowsi’s account of early Persian history is greatly at odds with what is accepted by today’s historians, and Newton is hard-pressed to reconcile it with his own chronology:

The histories of the Persians now extant in the East, represent that the oldest Dynasties of the Kings of Persia, were those whom they call Pischdadians and Kaianides, and that the Dynasty of the Kaianides immediately succeeded that of the Pischdadians. They derive the name Kaianides from the word Kai, which, they say, in the old Persian language signified a Giant or great King; and they call the first four Kings of this Dynasty, Kai-Cobad, Kai-Caus, Kai-Cosroes, Lohorasp, and by Lohorasp mean Kai-Axeres, or Cyaxeres: for they say that Lohorasp was the first of their Kings who reduced their armies to good order and discipline, and Herodotus affirms the same thing of Cyaxeres: and they say further, that Lohorasp went eastward, and conquered many Provinces of Persia, and that one of his Generals, whom the Hebrews call Nebuchadnezzar, the Arabians Bocktanassar, and others Raham and Gudars, went westward, and conquered all Syria and Judaea, and took the city of Jerusalem and destroyed it: they seem to call Nebuchadnezzar the General of Lohorasp, because he assisted him in some of his wars. The fifth King of this Dynasty, they call Kischtasp, and by this name mean sometimes Darius Medus, and sometimes Darius Hystaspis ... The sixth King of the Kaianides, they call Bahaman, and tell us that Bahaman was Ardschir Diraz, that is Artaxerxes Longimanus, so called from the great extent of his power: and yet they say that Bahaman went westward into Mesopotamia and Syria, and conquered Belshazzar the son of Nebuchadnezzar, and gave the Kingdom to Cyrus his Lieutenant-General over Media: and here they take Bahaman for Darius Medus. Next after Ardschir Diraz, they place Homai a Queen, the mother of Darius Nothus, tho’ really she did not Reign: and the two next and last Kings of the Kaianides, they call Darab the bastard son of Ardschir Diraz, and Darab who was conquered by Ascander Roumi, that is Darius Nothus, and Darius who was conquered by Alexander the Greek: and the Kings between these two Darius’s they omit, as they do also Cyrus, Cambyses, and Xerxes. The Dynasty of the Kaianides, was therefore that of the Medes and Persians, beginning with the defection of the Medes from the Assyrians, in the end of the Reign of Sennacherib, and ending with the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great ...

This Dynasty being the Monarchy of the Medes, and Persians; the Dynasty of the Pischdadians which immediately preceded it, must be that of the Assyrians: and according to the oriental historians this was the oldest Kingdom in the world, some of its Kings living a thousand years a-piece, and one of them Reigning five hundred years, another seven hundred years, and another a thousand years. (Newton 373-376)

The proliferation of competing Persian chronologies—the anonymous Chronicle of Nabonidus, Ptolemy’s Royal Canon, Manetho’s Aegyptiaca, the Seder Olam Rabbah, Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, not to mention a host of Classical historians—should at the very least alert us to the fact that the currently received chronology is not and never has been undisputed.

In Conclusion

Newton brings The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended to a conclusion by reiterating the theme of the whole work, namely, the tendency of ancient peoples to exaggerate the antiquity of their own civilizations:

We need not then wonder, that the Egyptians have made the Kings in the first Dynasty of their Monarchy, that which was seated at Thebes in the days of David, Solomon, and Rehoboam, so very ancient and so long lived; since the Persians have done the like to their Kings, who began to Reign in Assyria two hundred years after the death of Solomon; and the Syrians of Damascus have done the like to their Kings Adar and Hazael, who Reigned an hundred years after the death of Solomon, worshipping them as Gods, and boasting their antiquity, and not knowing, saith Josephus, that they were but modern.

And whilst all these nations have magnified their Antiquities so exceedingly, we need not wonder that the Greeks and Latines have made their first Kings a little older than the truth. (Newton 376)

In the final article in this short series, we will take a brief look at Newton’s Short Chronicle, which was appended posthumously as a preface to The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended.

To be continued ...

References

- Heinrich Walter Guggenheimer, Seder Olam: The Rabbinic View of Biblical Chronology, Jason Aronson, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc, Lanham MD (1998)

- Leo Depuydt, More Valuable than All Gold: Ptolemy’s Royal Canon and Babylonian Chronology, in Piotr Michalowski (editor), Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Volume 47, American Schools of Oriental Research, (1995)

- Ferdowsi, The Sháhnáma of Firdausí, Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Volume 4, Volume 5, Volume 6, English Translation by Arthur George Warner & Edmond Warner, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co Ltd, London (1905-1912)

- Ken Johnson, Ancient Seder Olam: A Christian Translation of the 2000-year-old Scroll, Kindle Edition, Biblefacts.org (2006)

- Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, in Ralph Marcus (translator), Josephus, Volume VI, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1958)

- Isaac Newton, The Original of Monarchies, Unpublished (1701)

- Isaac Newton, The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended, J Tonson, J Osborn, T Longman, London (1728)

- Herbert Weir Smyth (editor & translator), Aeschylus, Volume I, William Heinemann, London (1922)

- William Gillan Waddell (editor & translator), Manetho, The Loeb Classical Library, L350, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1964)

Image Credits

- Isaac Newton (1702): Geoffrey Kneller (artist), National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2881,Public Domain

- The Defeat of Astyages: Maximilien de Haese (designer), Jac. van der Borght (weaver), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Public Domain

- Aeschylus: North Carolina Museum of Art, © Alexisrael, Creative Commons License

- Esther Denouncing Haman to King Ahasuerus: Ernest Normand (artist), Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens, Public Domain

- Ferdowsi (Tus, Iran): Abolhassan Sadighi (sculptor), © Tasnim News Agency, Creative Commons License

- The Achaemenid Empire: William Robert Shepherd, The Historical Atlas (1923), Public Domain